9.1 A Place in Europe

1.

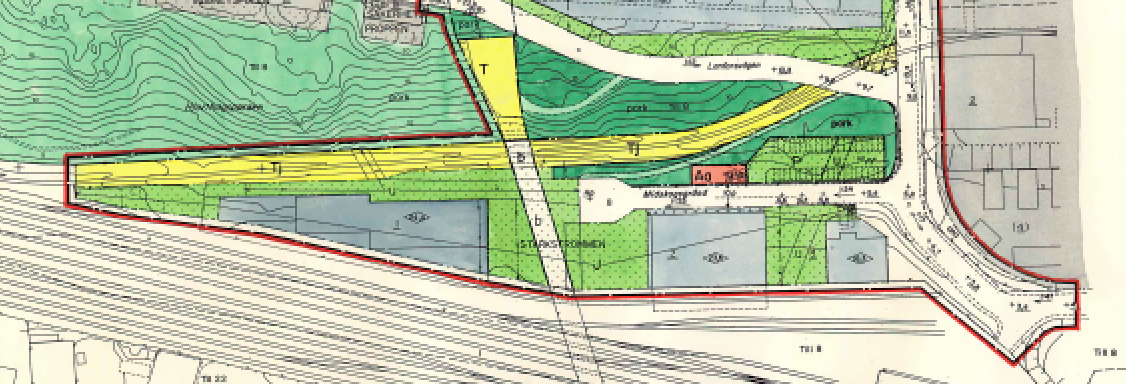

The place is demarcated by a highway, a large new development and some rocky hills with a grove of trees,1)A new biomass power plant is being built. Fortum is investing five billion kronor, which is the largest industrial investment in Sweden, it will be fueled using byproducts from the logging industry.

“Tillsammans skapar vi en grönare stad”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.fortum.com/countries/se/kampanjer/biobransle-vartan/pages/default.aspx. above are elevated subway tracks. It is lowered in the midst of the urban landscape, not particularly visible to passers by, the surrounding borders create a triangle where a sort of state of exception seems to be in effect – at least for some of those who live there. It’s a place in central Stockholm where a few hundred people live, work, and circulate, they’ve come from various countries in and outside Europe, some are Swedish citizens. They’ve come here for different reasons, what they all have in common is the hope of a more successful life. Some are doing short-term work in accordance with free movement, others are just sleeping here temporarily. It’s a place in transition. There are many similar places in Europe, they’re becoming increasingly common. But it’s also a place we’ve seen at previous points in Swedish history during large waves of migration. That is why my thesis touches down in a place like this, in this place. It ends by opening up a new inquiry where my questions can be put in play in new ways and a new work can begin to take shape.

2.

There are three five-story buildings here, two of them are empty and sealed up. When I search the city planners office for plans I find that the buildings are slated for demolition, but it doesn’t say when.

At the bottom of the slope that leads down to the middle house there are two campers, but there are no people visible nearby. I ask a construction worker passing by if he knows if anyone lives there. We speak English, each with our own accent. Yes, he’s seen people come out of them around six o’clock in the morning, he doesn’t know where they’re from because he’s never spoken with them. He tells me there are several other similar encampments around here.

– A few live over there, he points behind him.

– Where are you from? I ask

– From Portugal, I work there, he says and nods down the road to where a biomass power plant is being built. I go where he pointed. On the far end of the third five-story building there are two steel doors. The left door leads to a temporary shelter in the basement with about thirty beds, operated by the City Mission. I meet a few thirty-something men from Guinea.

– Wow, there are a lot of you living here.

– We go and look for work in the morning then we come back here. They gesture behind them and I see seven men exit a basement door to go smoke. One sits down, there’s only one chair. Several of them have come here through free movement, others are from countries outside of Europe.

– The two of us have residency permits in Portugal.

– How long have you been here?

– Two months.

They’re happy to talk to me but don’t want me to photograph them, say where they live, or give their names.

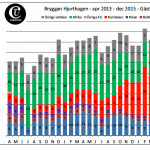

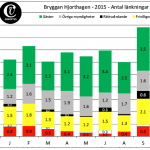

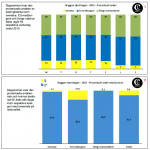

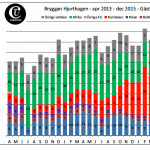

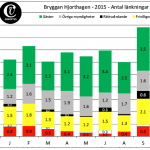

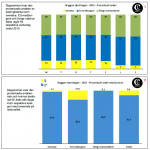

The steel door to the right goes to Convictus shelter for the homeless. Nina, who is the director at Convictus Bryggan tells me that during the coldest half of the year they only accept women at night and men in the daytime. Most of the women are from Romania and Bulgaria and have come here to beg. The men spend their evenings and nights recycling cans or doing various kinds of day labor. Just ten years ago middle-aged Swedish men with addiction issues were the biggest group at the shelter, today most are “third country nationals,” usually from North and West Africa.2)One of them is Thomas from Ghana, he is a former solider, who moved to Italy and got work and a residency permit but when the situation became too difficult he came to Sweden where he now has a residency permit. He’s been living outside, under the loading dock behind the House for two and a half years. Thomas distributes advertising between two a.m. and nine a.m. then goes to Convictus, eats, takes a shower, sometimes he does laundry there. He is one of those who wants to tell his story for the camera and comes up to us when he’s seen that we’ve been back every week or so for the past three months, to film the area and try to talk to people. A similar number are from Eastern Europe, mainly Romania.3)“Convictus Bryggan Hjorthagen”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.convictus.org/hemloshet/bryggan_ostermalm.html.

Those who stay here have “fallen through the cracks” between the structural exclusion and inclusion mechanisms of the system.

Those who stay here have “fallen through the cracks” between the structural exclusion and inclusion mechanisms of the system.

Every morning at half past six the doors open and a long trail of humans wander off with their belongings in blue Ikea bags. They’re going to the city to seek work, beg, and perhaps look for a different place to sleep, there is a lot of pressure on the shelters. At the same time about a hundred construction workers arrive at another entrance to the same building. They soon emerge again, wearing bright green and yellow vests, orange or red helmets. Those who haven’t gotten work stand around smoking, waiting their turn.

On the way back I see a van, the side door has been taken off it and is leaned up against it. After ascertaining that nobody’s there I raise my camera above the door and shoot. I look at the image; people are sleeping here too.4)I don’t think it’s okay to photograph other people’s bedrooms without their permission, but in this situation my assessment is that it’s more important to show how people live here. The photograph is an example of one of the ethics-aesthetics negotiations that constantly arise – decisions that must be made quickly and on site. When I include these two photos with my shadow I also want to show a transgression of a limit in which I am putting the viewer’s trust in my images and for this dissertation at risk. At times I misjudge, I encourage reflection on the part of the reader and viewer. The discussion about the ethical must be kept open. I ask a worker locking up the car next to me if he knows anything, but no, he has no idea what country the owners of the car are from, he says in a neutral tone. He’s from Poland.

3.

In and around the middle one of the three shuttered buildings, the one I call the House, there’s artistic activity – a self-organized cluster of artists have intervened in the environment with their art.

A new overpass has been built behind the buildings, far too close. There’s a loading dock along the back of the House. With the arrival of the overpass there’s no longer enough space to drive vehicles up to it for loading. But the overpass provides shelter to some. Next to the concrete wall they’ve made themselves sleeping places out of wooden pallets. They make their beds there every night.

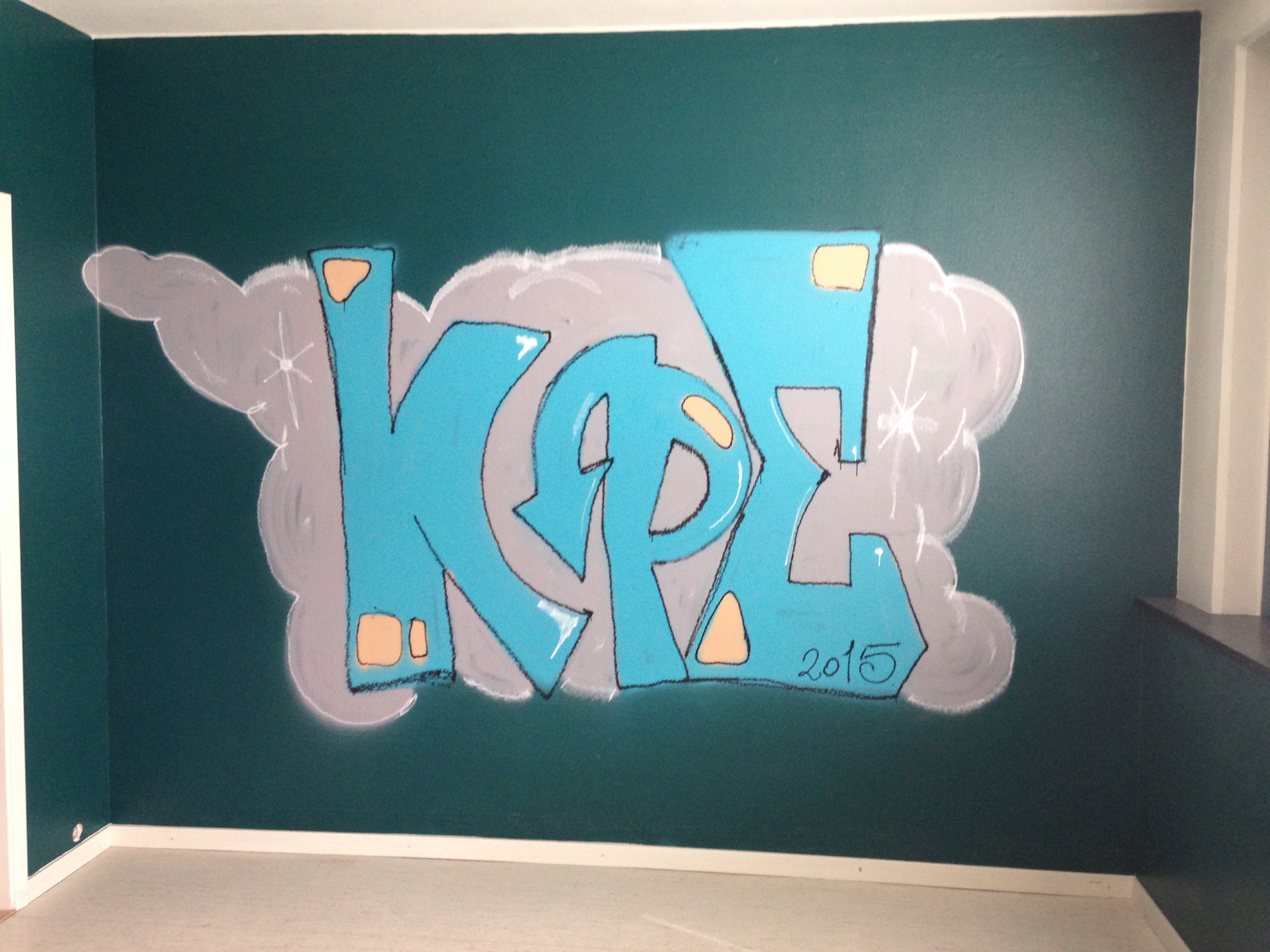

The location is secluded and they can sleep there relatively unbothered, a few security guards on patrol are the only people with a view of their open bedroom, and the guards appear to accept their presence. I’ve seen many similarly furnished, organized sleeping places in central Stockholm. There are about ten sections under the loading dock and I can glimpse rolled-up mattresses, clothes, and blankets under most of them. In one of these encampments several shoes are lined up. In the five-story building next to the loading dock there are about thirty rooms on each floor. In here, as well as outside, artists AKAY and KPE (KlisterPeter) [Glue Peter] and others have created a series of pieces. If they’d wanted and tried to get in, the homeless people might have found the ladder that the artists had hidden and seen that the window on the second floor can be opened. But they don’t seem to think along those lines. The begging people I’ve previously spoken with say that they don’t want to bother anyone, they want to live an orderly life, they don’t want to break rules and ordinances they want a home and a job. And the same is probably true of most of those who come here looking for work. They don’t want to be out there, but they don’t want to be in there either.

Outside the buildings a kind of bare life is underway5)“But in every judicial order there is an exception from order that in a kind of paradox regulates what applies when no order applies, in the state of exception. There the sovereign becomes precisely a sovereign again – and accordingly the citizen is reduced to a bare life. Agamben’s thesis is that this is ‘ultimate foundation of political power’ and thus the political essence that precedes every social contract.” So writes Ola Sigurdson, professor of religious studies and systemic theology at the University of Gothenburg, in an article about philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s book Homo Sacer. Ola Sigurdson, “Agamben visar hur kulturen inkräktar på livet”, Svenska Dagbladet, August 23, 2010. Accessed July 26, 2016, http://www.svd.se/agamben-visar-hur-politiken-inkraktar-pa-livet/om/kultur:under-strecket. and inside one of the buildings as well as outside there’s a kind of artistic activity. The transformation of the space is giving rise to both these activities. Urban spaces – that aren’t included in urban planning, and are still constituted in the city by people, such as the places, sleeping places, closets of begging – are not a representation of something, they are a political form in and of themselves. What forces are at work in this liminal space?

4.

I follow the artists into the House, there’s an alarm system on the first floor so we enter on the second floor using a ladder.6)AKAY and KlisterPeter gave me permission to use these documentations in my dissertation. I used my phone to photograph when I was in the House. The artists had been hired by Konstnärliga Forskarskolan, Lund University to hold a three-day seminar. Two of us Ph.D. students attended.

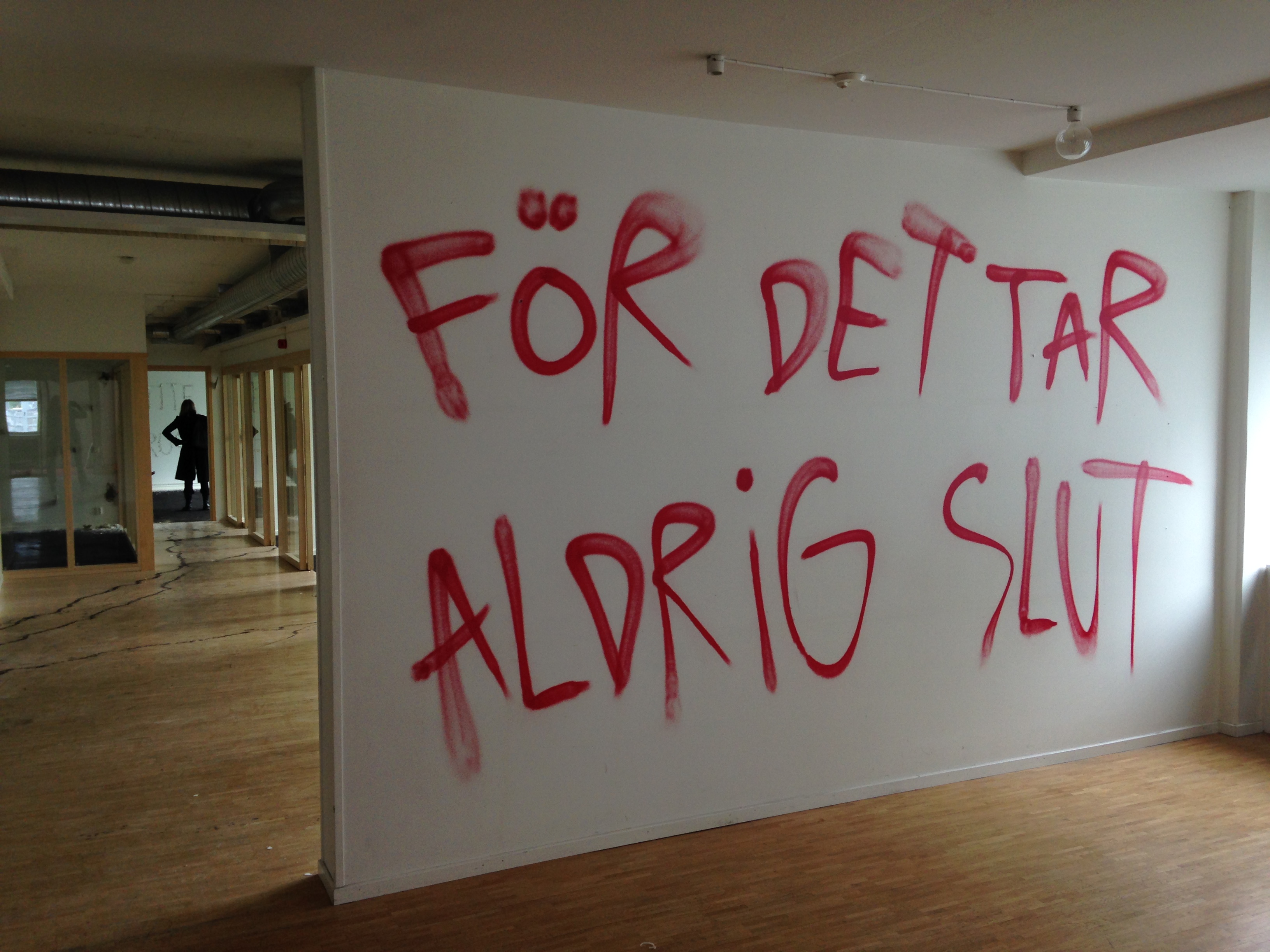

Paintings are often objects, but not here.7)Painting is one of the two-dimensional forms of production. Even if painting were to depict a three-dimensional form – visually an object – being and depicting isn’t the same (as discussed in chapter 2), in this way the depicted object is de-objectified. But here we are talking about the actual painting as an object that can be moved. Inside the former offices in the House paintings cover entire walls, they dissolve the wall visually as it becomes the painting and the painting becomes the wall. Words have been painted here, mostly with the tag KPE (KlisterPeter) and the signatures of other artists, but also sentences, comments.

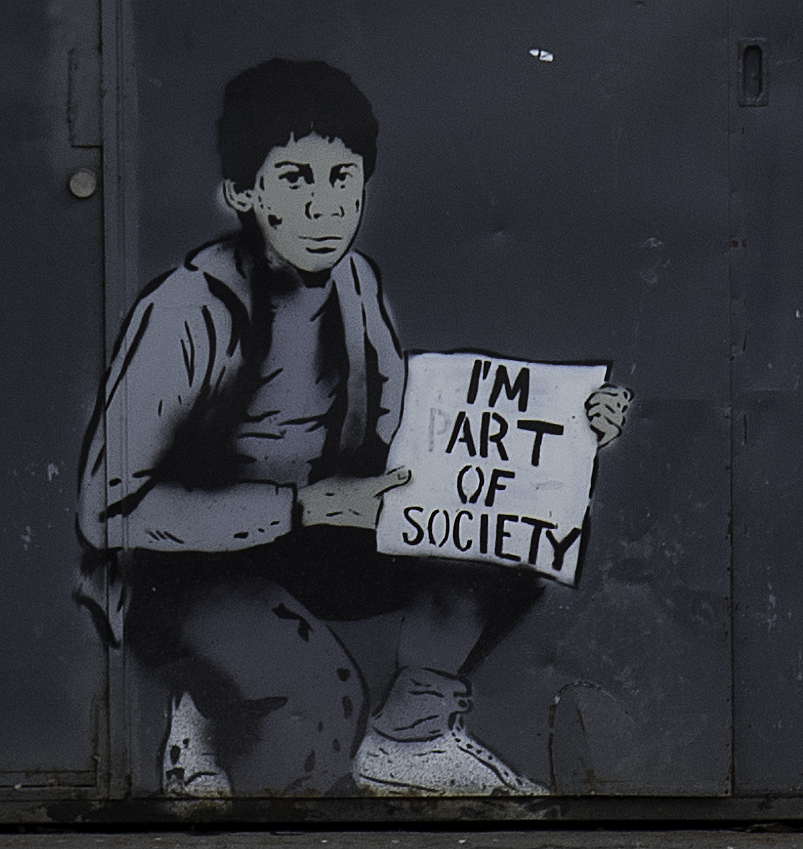

It brings to mind how graffiti artists from all over the world have painted the Israeli wall since it began to be built in 2003. How people have swarmed to the wall since it was built and left a multitude of messages, symbols, images behind.8)“Grafitti” originally comes from the Greek “grapho” meaning to write, and is the plural of “inscription” in Italian. As if to dissolve what is grey and compact and open up what blocks vision and movement of bodies.9)In the news segment about the paintings on the Israeli wall, Banksy’s among others, I say: “Those who paint appear to want to open the wall, dissolve the concrete with their images and texts.” The segment was made for the Swedish TV program KOBRA, SVT, 2006. It can also be found here: https://vimeo.com/95277443.

I paint signs to show that, “I was here,” my sign is my testimony. Being on the side of the demarcated means something to me. When you read these signs they get imbued with meaning. The sign connects us. To see images is an act.

5.

How is this art connected to the (transmission of) meaning and content?10)Art critic Fredrik Svensk expresses the importance of constantly trying to understand in the face of what images art is made and can be made: “Because aren’t mechanisms of exclusion and inclusion that take place mainly on a sensual basis far more important to understand today than those that happen through a conventional politics of selection and representation?” A review of the Nordic pavilion in Venice 2015. Frederik Svensk, “Paviljongen som exklusiv symfoniorkester”, Kunstkritikk, May 14, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.kunstkritikk.se/kritikk/paviljongen-som-exklusiv-symfoniorkester/?d=se. For whom, for what, is this art made? When the two artists, AKAY and KlisterPeter, talk about their art they claim to give without expecting anything in return. It seems to me that their idea of what art is unites them; with friendship, trust, they make art alone and together with other artists that come there. But what do they mean by giving? To whom or what do they give? Can one give if there’s no one there to receive? What kind of giving is this?

Architect and artist Gordon Matta-Clark is central to their practice, as is his “anarchitecture”, “recycling pieces and spaces”, and “building cuts”. Gordon Matta-Clark’s art has been shown and can be discussed since he documented it on photo and film, so too the site-specific performances. Architecture and its compatibility with the urban life of the space was a central concern. Matta-Clark explains that he spent months in Guatemala, and that after he got back he wandered about New York City to find a space to stage The Making of Pier 52.11)“And so, after coming back from places where architecture and architecture disintegration is in an incredible state of colossus in Guatemala, I was just determined to start something.” Gordon Matta-Clark; Gloria Moure, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings, (Barcelona: Polı́grafa; New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2006), 180. He did not apply for a permit for this, or many of his other works, but he wasn’t interested in himself – when he created the works – or the viewer feeling uncomfortable. It wasn’t the forbidden, the transgression, or the crime that he was after, even though his works often included those things, Matta-Clark says in an interview that the work doesn’t need that, if anything it’s a burden. What he wanted to show couldn’t be done in another place or in a different way. “Well sneaking in may be attractive to some people, but I’m not interested in that. That’s maybe a flaw, as far as I’m concerned. Because I think the space and the situation is perfectly valid on it’s own.” The interviewer, Liza Bear asks: “Presumably you spent a fair amount of time working on it, I imagine…”12)Ibid., 180. GM-C: “Oh, well that aspect is something else. LB: Considerable expense. GM-C: Well, I mean, whether or not the piece will have a public life of any kind. Of course at the moment, it remains a confiscated work.”13)Ibid., 180.

Gordon Matta-Clark’s practice introduced new and radical forms of art. Some of his most famous projects involved laboriously cutting holes in the floors of abandoned buildings: “Well, originally it had to do with cutting out slices or wedges of […] the imperial New York waterfront.”14)Ibid., 178. Or in the case of Splitting (1974); dividing a suburban home in two. “Dealing with nothing more complex than the limits of human scale.” Rooms, houses, or a space where a particular human activity has taken place at a certain point in history, are opened and restructured for new activity for the future. For AKAY and KlisterPeter the choice of building is less about architecture. They’re wanderers in the city, they find a place where they practice for a while. Is it a studio? No, because this art can’t be moved to an exhibition space. Is it an exhibition space? No, viewers don’t come here. This building has an alarm on the first two floors; AKAY and KlisterPeter might not get in tomorrow.

When structures change voids – anomies – can emerge, fictions are created in anomies.

Art mediates meaning, which meaning are we talking about? The words DAMAGE, BEAUTY, and BRICK are carved out in different ways and in different materials. This isn’t about embodying sculptures, this is the opposite – the artists have cut out the word BEAUTY in a sliding wall, the word unfolds as one pulls the wall out. Why did they choose that word? Beauty is an aesthetic term. In an interview Louise Bourgeois says: “Beauty? It seems to me that beauty is an example of what the philosophers call reification, to regard an abstraction as a thing. Beauty is a series of experiences. It is not a noun. People have experiences. If they feel an intense aesthetic pleasure they take that experience and project it into the object. They experience the idea of beauty, but beauty in and of itself does not exist. […] In fact, beauty is not only a mystified expression of our own emotion.”15)Louise, Bourgeois, Deconstruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father, (London: Violette Editions, 1998), 358. The word BEAUTY is cut out of the viewer’s projection surface – the viewers in this case are the artists themselves – they create and are also spectators within their community, and they tell me other artists come here, they’re part of a cluster, it’s a self-organized activity – the hollow word is folded up with the sliding door and can unfurled. They de-objectify the idea with a void and leave it open. Beauty is left open, to be filled with meaning.16)For me it’s a clear idea and act. Since my work in South Africa and Palestine/Israel I’ve expressed beauty as that which opens. For instance I say about the film A Heart From Jenin that the gift of the heart opens the wall and when it’s received by the family in Israel this opening is actually a hole in the language – and the images – that uphold the wall. As an Israeli friend put it: the wall was in the language before it was built. BRICK, BEAUTY, and DAMAGE – the words have been cut out of the walls and become openings in the structure of the building. They open the question – who and what is to fill these open terms, in this place waiting for transformation, with meaning?

Between that which will be done and that which is done, between future and present tense, there’s a transformation process – a process that demands time and space for itself. It can feel like free fall, or like a condition of the possibility of possibilities, but strangely it is also a lack of freedom; because not-knowing is a condition in which one becomes dependent on what one is going to learn from (by, with). The mental process is dependent on the response of the matter.

I walk through my thesis, chapter after chapter, room after room, hallway after hallway. Ceilings and walls are caving in inside the building. Because something must be visualized using other means – an economy of giving that doesn’t merely measure and belongs to the territorial. One wall reads: “Because it never ends”.

6.

In one of the rooms in the House the window shades have been attached to each other so that they can be raised and drawn at the same time. Window shades are part of this building they’re in every room, over the years many hands have raised and lowered them daily – with a certain force and at a certain pace. I pull the ring and need to use my entire body for leverage to pull up eighteen shades at once. They rattle. I’m almost blinded by the light that I let in before I let go of the ring and the shades fall down with a loud bang.

The importance of the collective eye – its limiting community. (When I slip and fall on the street and quickly brush my pants off and pretend as if nothing happened – who is assumed to be watching? Why do I think anyone sees me on the street? I am seen by the public eye, but don’t I also dress myself in this gaze, these gazes?) Let us call those who see – with all their senses, all their body – one.

Like Gordon Matta-Clark, AKAY and KlisterPeter help us to divide the sensual, both in the sense of splitting and sharing.

7.

Their art can’t be moved or sold, it can’t be part of economic transactions. The artists give their time, their energy, their desire, without demands for reciprocation. Neither their work inside the House or the spray-painted images and messages outside it can “participate in the circulation of representations of representations.”17)I’ve borrowed this expression from Peggy Phelan. Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. (New York: Routledge, 1993). See also chapter 1.2, “Notes on the Text”, about performance. So why is this (art) interesting? The method is performative.18)“Thus while performance can be understood as a deliberate ‘act’ such as in theatre production, performance art or painting by a subject or subjects, performativity must be understood as the iterative and citational practice that brings into being that what it names.” writes Barbara Bolt, on page 134, referring to Judith Butler. “Butler is very clear that performativity involves repetition rather than singularity. Performativity is ‘not a singular act for it is always a reiteration of a norm or set of norm, and to the extent that it acquires an act-like status in the present, it conceals or dissimulates the conventions of which it is a repetition.’”

Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A performative paradigm?” PARSE, No. 3 (2016). Accessed August 6, 2016, http://www.parsejournal.com/article/artistic-research-a-performative-paradigm/. “Performance resists the balanced calculations of finance. It saves nothing, it only spends,”19)Phelan, 148. writes Peggy Phelan. But this isn’t a wasteful resistance, not consumption with the ulterior motive of accumulation, but a lusty transgression.20)Michael Richardson writes, in his interpretation of philosopher George Bataille:

“If we stick to facts capitalism doesn’t escape the dialectical logic of Bataille: It consumes, and consumes just as meaninglessly, just as wastefully as any other society. What capitalism is lacking isn’t the consumption but every kind of lusty transgression. When we waste we do it grudgingly, all the time and with an ulterior motive of ultimately accumulating.” Michael Richardson, Georges Bataille. (New York: Routledge, 2005), 79. Another thing that makes this art interesting is that the artists don’t work alone, other artists are active here, nor do they work as a group. “Individual genius is not the origin of culture,” as Rasmus Fleischer and Samira Ariadad write in their essay “Att göra gemensamma rum” [Creating common spaces].21)“Individual genius is not the origin of culture, as the tenacious myth of the originator without communities would have it. These communities too need to happen, especially in the gray areas, like rehearsal spaces. According to a liberal view on culture, ‘culture’ is something free floating – culture doesn’t need to happen and it doesn’t need community.”

Samira Ariadad and Rasmus Fleischer, “Att göra gemensamma rum”, Brand, No. 1 (2010), 44–6. Accessed July 7, 2016, www.samhallsentreprenor.glokala.se/wp-content/uploads/Att_gora_gemensamma_rum.pdf. They describe a system that has embraced the liberal idea that the private and the public are opposites, and that income for sustenance is won and communities found through a dialectical struggle. But what’s in between, in the act of giving without getting anything in return; these artists are well aware that they won’t make a livelihood off their work. The art will be torn down with the House. Could they be investigating if art can hold this kind of giving? Perhaps it’s exactly this kind of giving that makes art interesting and important, a certain kind of art, at any rate. And here, in this kind of place, there is the possibility of developing the kind of giving that isn’t about creating artifacts that are a part of the economy of reproduction.22)Banksy is another artist who activates urban spaces, who visually questions demarcations through his art, but also as reproduction and transaction. Sales of his paintings in Gaza and on the Israeli wall have been attempted on the art market. “Now I think that even if [Banksy] drew something very small – even a dot – people might cut down their walls and try to sell it.” Says Ayed Arafah from the Dheisha refugee camp in Bethlehem. Yolande Knell, “Gaza Family ‘Tricked’ into Selling Banksy Painting for $175”, BBC News, April 1, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-32139657. The artists found this place and began. What they get in return is something beyond that – space, meaning, content, freedom? It’s not limitless giving. “As described by anthropologist Marcel Mauss in his classic work The Gift transactions of gifts – and counter gifts […] contribute to social cohesion.”23)Full quote: “As the French anthropologist Marcel Mauss argues in his classical work The Gift from 1925, transactions of gifts and gifts in return – in welfare state terms, the taxation of work in exchange for risk spreading and social protection – contribute to social cohesion.” Hanna Bäckström, Johan Örestig, Erik Persson, “The EU Migrant Debate as Ideology”, Eurozine, June 15, 2016, 2. Accessed April 26, 2016, http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2016-06-15-orestig-en.html. When this is put into practice self-organized communities can be created. They have no political agenda but the political is constantly present – they work according to a system of their own, create a social script of their own and make their art. Perhaps this is the meaning they want to pour into the empty word BEAUTY – in itself an inexhaustible term. The collective practices of the House create a certain kind of artistic expression. There is a sort of “undetermined openness, when aesthetic experience is connected to freedom,” when communities emerge and are formed, according to philosopher Sven-Olof Wallenstein. “On another level, this floating dimension, between ideas and things, subjective and objective, frame and non-frame, depends on desire not being private or internal, but coming directly from our ability to communicate, from that which opens on intersubjective community – because this, Kant says in the important §9, is ‘the key to the critique of taste,’”24)Sven-Olof Wallenstein, “Kant, det sköna och det sublima”, Paletten, No. 4 (2015): 59. according to Wallenstein. Desire is also associated with a temptation beyond the moral, beyond the known, with an attraction to the foreign, and to the non-doable. If the limit is transgressed the sublime can be reached, transgression is part of the method. It’s not just walls, surveillance, it is also the beautiful or the ugly – and images of what’s beautiful or ugly – that is transgressed when communication is opened (the spray-painted messages outside and inside, the cut-out words in the walls). Desire is associated with communicability. Not through the usual channels of communication – but through prohibited communication by aerosol can. “The aesthetic economy is always dependent on a border between the internal and the external (the frame as an on the side of, outer-work, parergon) that neither belongs to the internal nor the external, and that can be understood as a framing effect that always remains unstable: the frame is always about to crack, at the same time as it can never completely fall away, and de-framing and framing are like two vectors, the interplay of which constitutes the dynamics of the aesthetic field, and where one will always refer to the other,”25)Ibid., 59. as Sven-Olof Wallenstein puts it.

8.

The question of what kind of place this is remains. The fact that the House and the surrounding area are under surveillance means that the area is a place in some sense. It’s not an obvious non-place, since the surveillance makes it a place in some sense. Those I’ll speak to half a year later – the cleaning firm that participates in evictions – calls places like this X-places, but the people who work at the shelters don’t like that, the situation here is their existence, their reality. That’s also why it isn’t a “non-place” in anthropologist Marc Agué’s sense where the place is contracted and the person becomes anonymous through the nature of the place.26)Marc Augé, Non-Places: An Introduction to Anthropology of Supermodernity, (New York: Verso, 1995), 101. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~jread2/Auge%20Non%20places.pdf. This place is also populated by people, the shelters, the encampments; people who use it in various ways, the workers’ locker- and break-rooms. Thomas and Samuel have lived under the loading dock for two and a half years. It’s something between a place and a non-place. It’s a liminal space that could be described as “vague terrain” – a designation for unproductive, undefined places that have been abandoned, often placed between exploited productive places in a city.27)Ignasi de Solà-Morales, Catalan architect, historian and philosopher, coined the term terrain vague, applied to abandoned, obsolete and unproductive areas, with no clear definitions and limits.

——“Ignasi de Solà-Morales”, Wikipedia. Accessed July 26, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignasi_de_Solà-Morales.

——“With the coining of the term Terrain Vague, Ignasi de Solà-Morales is interested in the form of absence in the contemporary metropolis. This interest focuses on abandoned areas, on obsolete and unproductive spaces and buildings, often undefined and without specific limits, places to which he applies the French term terrain vague. Regarding the generalized tendency to ‘reincorporate’ these places to the productive logic of the city by transforming them into reconstructed spaces, Solà-Morales insists on the value of their state of ruin and lack of productivity. Only in this way can these strange urban spaces manifest themselves as spaces of freedom that are an alternative to the lucrative reality prevailing in the late capitalist city. They represent an anonymous reality.” “Terrain Vague”, Atributos Urbanos. Accessed July 26, 2016, http://atributosurbanos.es/en/terms/terrain-vague. But that’s not quite right either, this area isn’t abandoned and will be populated, it is populated and activated. It’s not a place in transition but a place that is waiting – a waiting place – the condition of the place creates the conditions for art because perhaps this is exactly what makes it attractive for artists to claim. They encroach on such places.28)“A gradual advance beyond usual or acceptable limits: urban encroachment of habitat.” “Encroachment”, Oxford Dictionaries. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/encroachment. The artists ponder the House and the place while they create – with their images they reflect upon what’s going on here and in that way they also indirectly relate to the migrants and guest workers that populate the place. (And perhaps the condition of the place even dictates the practice of an [unknown] number of artists.) I too encroach on it. But my work emerges in a different way, I have a different method, but I plug into the art of the other artists since it will appear in my images and recordings. I too create activity in this place, which demands that I connect to the people who live and work here, and negotiate which images should be made visible. In this sense the place is a space for negotiation. When different realities meet negotiations arise between different parties that inhabit a place, the homeless, artists, workers, guards, property owners, when abandoned or soon to be demolished houses are used in ways other than those planned or expected. The place as political form poses questions of when and between which logics and parties negotiations will be initiated, how and over what. Which parties will participate? It’s a place waiting to be made visible.

9.

I return four months later, on a cold and clear fall day in 2015. I want to speak to the people here. For a while now it’s been impossible to get into the House, the artists say that new alarm systems have been installed and that their previous points of entry have been closed. I wander around outside, where the docks used to be there are now two shacks.

Two men walk toward me. We greet and strike up a conversation; they’re from Algeria. One of them, who I speak English with, shows me his residency card from Spain, he can live there for twelve years. His family is there and they live in a house, but he lost his job and came here a few weeks ago to try to find a livelihood and now lives in a shack that he’s built himself.

– It’s not human to live like this, he says and shows me.

– It’s getting cold.

– Yes, I’m going to Spain soon, I give up, you can’t get work here without a personal identification number and I don’t want to do what the Romanians do – they beg, I’d never do that.

The need and necessity is visible and raw.

10.

I continue coming here during the spring of 2016 with filmmaker Erik Pauser. I’ve received a project grant to film the area and I want to develop a choreography with the dancer Anna Westberg. I speak to among others Thomas, 45, who has a residency permit and two jobs but is homeless and living under loading dock of the House. Samuel, 35, does too. He is homeless and undocumented from Ghana/Togo. And Albert, from Nigeria who has a residency permit and a job. Leonas from Lithuania has lost his passport and his cellphone and is living in the yard. Mohamed is from Libya and has had a residency permit for eight years, he can only find temporary work, usually off the books and lives in one of the shacks under the freeway. Said, 38, from Morocco, who’s just gotten his personal identification number and begun taking Swedish classes for immigrants lives in the shack across the way. Nina from Finland, the director at Convictus. Maria, a begging person from Romania who sleeps at the shelter sometimes. We speak with Arne who has had homes and been homeless and now manages daytime activities at Convictus and with Michaela from Romania who works with the women’s night operations. We also speak to a few workers from Poland and from Ireland, and one foreman from Sweden. But neither the management company for the House, the cleaning company, nor the owners of the alarm company – all established businesses in Sweden want to talk to us.

An afternoon in June a truck, dumpsters, the cleaning company, the alarm company, the house management, and the police arrive. They clear all encampments on the property, including those under the loading dock behind the House and Leonas’ home under the bike shack. But not the other shacks around, because they’re on land that belongs to the transportation authorities and the City of Stockholm. Those who tear out and throw away other people’s personal effects don’t want to be filmed and try to stop me, but since I’m standing on ground owned by the City of Stockholm I can film what’s going on. Those who are doing the cleaning especially don’t like me filming, even after I’ve explained that I’m not focusing on faces, but what they’re doing. They react strongly and emotionally. Two policemen are emotional too and want to stop me, while another policeman comes up and asks why and wants to listen. The homeless whose temporary homes are being put in the dumpster want me to film and they tell their stories in front of the camera.29)A synopsis of the project “A Place in Europe” can be found at www.ceciliaparsberg.com. From these stories and events I want to develop a filmic choreography that builds on my work with different forms of images of the gestures of begging and giving in the urban space.

11.

There’s a demolition permit for the House, but the owners don’t have a permit to build something new in its place, which I find out after talking to the city planning office. Long before the eviction, around the time I’d first started filming the area, I’d met Anders, owner of the company Destroy that manages the alarm and surveillance for the House. We chatted and I got to follow him into the House. He showed me BRICK and said with admiration in his voice: “They cut this out using a hand saw.”30)I haven’t been able to get in since. The owners of the House won’t give permission despite my referring to research at the university. In one of my conversations with them to try to convince them to let me in so that I can film the project manager suddenly blurts out: “For the love of god I hope you’re not making a film about the bums on the site?” I regard this comment as interesting in this context and will leave it here for the reader to interpret.

The House is a structure where lives are lived and arranged. Or is it life – living – that limits activities and gives rise to the House? Lives that have been separated – by an imagined structure – can also be connected – by a lived structure – but not without hope of something else.

This is how Hannah Arendt describes the phenomenon of houses: “It implies ‘housing somebody’ and being ‘dwelt in’ as no tent could house or serve as a dwelling place which is put up today and taken down tomorrow. The word house, Solon’s ‘unseen measure,’ ‘holds the limit of all things’ pertaining to dwelling; it is a word that could not exist unless one presupposes thinking about being housed, dwelling, having a home. As a word house is a shorthand for all these things.”31)Hannah Arendt, “Thinking and Moral Considerations: A Lecture”, Social Research, Vol. 38, No. 3, (Autumn 1971), 430–1. Accessed July 29, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40970929. Hannah Arendt writes of thinking that a meaning can be reclaimed by contemplating a word: “The word house is something like a frozen thought that thinking must unfreeze, defrost as it were, whenever it wants to find its original meaning.”32)The sentence continues “In medieval philosophy this kind of thinking was called meditation, and the word should be heard as different from, even opposed to, contemplation.”

Ibid., 431. And this house stands as an empty structure, a place waiting for transformation. A frozen thought in the middle of Stockholm. In some ways disconnected from, but still linked to, the prevailing social structure.

In this place waiting for transformation, there are hopes.33)Every year the Stockholm region grows by 35,000 inhabitants. The number comes from information about Värta and Hjorthagen where this place-non-place is located. “Vi bygger om Värtahamnen”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.stockholmshamnar.se/stockholm/vi-bygger-om-vartahamnen. In those who come to seek work in Sweden and try to get residency permits and personal identification numbers, in the homeless who build themselves temporary shacks, in those who come to beg, in those who come to work at Sweden’s largest biomass power plant, in those who work for the aid organizations – civil society’s organized support for the homeless and others who “fall through the cracks”, in the older couple in one of the campers whose son got a job in Stockholm, in the construction company that has gotten a demolition permit for the buildings, but no permit for a new building, in the artists to continue creating, in the person who with a repetitive motion reaches out a hand waiting for a response and hopes that this response will mark the start of a negotiation.

12.

The short introductory story about my non-encounter with a begging person on the street contains everything that this dissertation is about and has developed. I’ve wanted to show how the situation on the street is a multi-dimensional experience, what layers the interaction between the begging person and me might contain. By beginning with that story I’ve wanted to show how a seemingly commonplace action and reaction to another person can be revealed aesthetically with an ethical argument. And vice versa. I devote myself to interactions, gaps: the ethics of place, the sphere between one and another. To me respect is a question of how we should handle this atmosphere where there also must be room for the third.

The first part of the dissertation was about investigating and revealing the images that are put into play between begging and giving in the urban landscape. Embodied hegemonic images both separate and connect bodies. That’s why the next step was to try to decode social scripts together with givers and stage new movements. That led to The Chorus of Begging and the Chorus of Giving which doesn’t strive to replicate a social situation, but replaced it with a choreography that reveals a negation – the arrangement of the choruses demonstrates another order that demands other actions with one another, in terms of language, movement, and attitude, and training was needed – it was a social choreography in cultural theorist Andrew Hewitt’s sense of the term: “I use the term social choreography to denote a tradition of thinking about social order that derives its ideal from the aesthetic realm and seeks to instill that order directly at the level of the body.”34)Andrew Hewitt, “Choreography as a Way of Thinking about the Relationship of Aesthetics to Politics”, Documenta magazine project (2007). Accessed May 24, 2016, www.old.tkh-generator.net/en/openedsource/andrew-hewitt-choreography-a-way-thinking-about-relationship-aesthetics-politics-0. In the interview he talks about his book. Andrew Hewitt, Social Choreography: Ideology as Performance in Dance and Everyday Movement, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005). When the installation is shown it doesn’t just make visible the interaction of the two choruses, but also the space between them. The arrangement of the two choirs is a choreographed “co-presence” – that denotes a space for social interaction – and in the installation it becomes a space that necessitates the viewer.35)Here choreography is about how bodies dispose of their performativity spatially. They stood across from each other – five meters apart – when they were filmed and the footage is projected the same way in the installation. A space for negotiation is being revealed and a space for action where the viewer is included in the negotiated dialogue on film. The meeting space that was established when they trained and sang together became a political form. As Andrew Hewitt describes: “Choreography is not just another of the things we ‘do’ to bodies, but a reflection on – and enactment of – how bodies ‘do’ things, and on the work that the work of art performs. Social Choreography exists not parallel to the operation of social norms and structures, nor is it entirely subject to those structures. It serves – ‘catachritically’, we might say – to bring them into being.”36)Andrew Hewitt who isn’t a practitioner himself, he is Professor of Germanic Languages and Comparative Literature, stresses: “In a sense, my training in literary studies puts me at something of a disadvantage in talking about my ‘relation to performance studies’ because that relation, I think, might be better explicated from the other side of the dialogue, from the perspective of performance itself. It is certainly not my aim to offer prescriptions to performers, but to raise possibilities – perhaps in the realm of theory only – that they themselves might then articulate.” Hewitt, “Choreography as a Way of Thinking about the Relationship of Aesthetics to Politics”. The purpose of The Chorus of Begging and the Chorus of Giving is to generate new images and movements, both in the participants and in viewers of the installation and thus also impact social life. I’ve also tried other ways of showing the work, such as screenings on streets or in parks. As a work The Chorus of Begging and the Chorus of Giving can’t be separated from how it was made, together with the production film it constitutes a blueprint for how a space of action can be created between the begging and the giving.37)The aesthetic as independent of the ethic, according to previous reasoning about image, see chapter 2 in particular. See also chapter 1.2 “Notes on the Text”, the passage on art activism. That is what my thesis – with my methodological intent – can be said to have led to. If we are to be able to discuss the ethical – which is necessitated by the political – the process needs to be made visible as well as the result, that is to say the method that is developed in the thesis. “Actions – not just representations – are ideological,” Andrew Hewitt writes. By social choreography Hewitt means that ideology becomes visible, becomes embodied, in the shifts between discourse and action as ideology.38)Hewitt, Social Choreography, 11. I didn’t make the production film as a documentary to attempt to explain the process – that would only reduce the power of the “work of art,” but as a document the purpose of which isn’t to create an exclusive work, but an inclusive one – though one that can’t be part of circular reproduction. Within artistic research such a practice can be developed, methods can be developed, another form of art be produced. While scientific research is dependent on the result, artistic research can counteract by emphasizing the thesis as the act of receiving the relay baton, continuing the process and accounting for the handover.

Chapter 9: Places III

Notes

| 1. | ☝︎ | A new biomass power plant is being built. Fortum is investing five billion kronor, which is the largest industrial investment in Sweden, it will be fueled using byproducts from the logging industry. “Tillsammans skapar vi en grönare stad”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.fortum.com/countries/se/kampanjer/biobransle-vartan/pages/default.aspx. |

| 2. | ☝︎ | One of them is Thomas from Ghana, he is a former solider, who moved to Italy and got work and a residency permit but when the situation became too difficult he came to Sweden where he now has a residency permit. He’s been living outside, under the loading dock behind the House for two and a half years. Thomas distributes advertising between two a.m. and nine a.m. then goes to Convictus, eats, takes a shower, sometimes he does laundry there. He is one of those who wants to tell his story for the camera and comes up to us when he’s seen that we’ve been back every week or so for the past three months, to film the area and try to talk to people. |

| 3. | ☝︎ | “Convictus Bryggan Hjorthagen”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.convictus.org/hemloshet/bryggan_ostermalm.html.    |

| 4. | ☝︎ | I don’t think it’s okay to photograph other people’s bedrooms without their permission, but in this situation my assessment is that it’s more important to show how people live here. The photograph is an example of one of the ethics-aesthetics negotiations that constantly arise – decisions that must be made quickly and on site. When I include these two photos with my shadow I also want to show a transgression of a limit in which I am putting the viewer’s trust in my images and for this dissertation at risk. At times I misjudge, I encourage reflection on the part of the reader and viewer. The discussion about the ethical must be kept open. |

| 5. | ☝︎ | “But in every judicial order there is an exception from order that in a kind of paradox regulates what applies when no order applies, in the state of exception. There the sovereign becomes precisely a sovereign again – and accordingly the citizen is reduced to a bare life. Agamben’s thesis is that this is ‘ultimate foundation of political power’ and thus the political essence that precedes every social contract.” So writes Ola Sigurdson, professor of religious studies and systemic theology at the University of Gothenburg, in an article about philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s book Homo Sacer. Ola Sigurdson, “Agamben visar hur kulturen inkräktar på livet”, Svenska Dagbladet, August 23, 2010. Accessed July 26, 2016, http://www.svd.se/agamben-visar-hur-politiken-inkraktar-pa-livet/om/kultur:under-strecket. |

| 6. | ☝︎ | AKAY and KlisterPeter gave me permission to use these documentations in my dissertation. I used my phone to photograph when I was in the House. The artists had been hired by Konstnärliga Forskarskolan, Lund University to hold a three-day seminar. Two of us Ph.D. students attended. |

| 7. | ☝︎ | Painting is one of the two-dimensional forms of production. Even if painting were to depict a three-dimensional form – visually an object – being and depicting isn’t the same (as discussed in chapter 2), in this way the depicted object is de-objectified. But here we are talking about the actual painting as an object that can be moved. |

| 8. | ☝︎ | “Grafitti” originally comes from the Greek “grapho” meaning to write, and is the plural of “inscription” in Italian. |

| 9. | ☝︎ | In the news segment about the paintings on the Israeli wall, Banksy’s among others, I say: “Those who paint appear to want to open the wall, dissolve the concrete with their images and texts.” The segment was made for the Swedish TV program KOBRA, SVT, 2006. It can also be found here: https://vimeo.com/95277443. |

| 10. | ☝︎ | Art critic Fredrik Svensk expresses the importance of constantly trying to understand in the face of what images art is made and can be made: “Because aren’t mechanisms of exclusion and inclusion that take place mainly on a sensual basis far more important to understand today than those that happen through a conventional politics of selection and representation?” A review of the Nordic pavilion in Venice 2015. Frederik Svensk, “Paviljongen som exklusiv symfoniorkester”, Kunstkritikk, May 14, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.kunstkritikk.se/kritikk/paviljongen-som-exklusiv-symfoniorkester/?d=se. |

| 11. | ☝︎ | “And so, after coming back from places where architecture and architecture disintegration is in an incredible state of colossus in Guatemala, I was just determined to start something.” Gordon Matta-Clark; Gloria Moure, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings, (Barcelona: Polı́grafa; New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2006), 180. |

| 12, 13. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 180. |

| 14. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 178. |

| 15. | ☝︎ | Louise, Bourgeois, Deconstruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father, (London: Violette Editions, 1998), 358. |

| 16. | ☝︎ | For me it’s a clear idea and act. Since my work in South Africa and Palestine/Israel I’ve expressed beauty as that which opens. For instance I say about the film A Heart From Jenin that the gift of the heart opens the wall and when it’s received by the family in Israel this opening is actually a hole in the language – and the images – that uphold the wall. As an Israeli friend put it: the wall was in the language before it was built. |

| 17. | ☝︎ | I’ve borrowed this expression from Peggy Phelan. Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. (New York: Routledge, 1993). See also chapter 1.2, “Notes on the Text”, about performance. |

| 18. | ☝︎ | “Thus while performance can be understood as a deliberate ‘act’ such as in theatre production, performance art or painting by a subject or subjects, performativity must be understood as the iterative and citational practice that brings into being that what it names.” writes Barbara Bolt, on page 134, referring to Judith Butler. “Butler is very clear that performativity involves repetition rather than singularity. Performativity is ‘not a singular act for it is always a reiteration of a norm or set of norm, and to the extent that it acquires an act-like status in the present, it conceals or dissimulates the conventions of which it is a repetition.’” Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A performative paradigm?” PARSE, No. 3 (2016). Accessed August 6, 2016, http://www.parsejournal.com/article/artistic-research-a-performative-paradigm/. |

| 19. | ☝︎ | Phelan, 148. |

| 20. | ☝︎ | Michael Richardson writes, in his interpretation of philosopher George Bataille: “If we stick to facts capitalism doesn’t escape the dialectical logic of Bataille: It consumes, and consumes just as meaninglessly, just as wastefully as any other society. What capitalism is lacking isn’t the consumption but every kind of lusty transgression. When we waste we do it grudgingly, all the time and with an ulterior motive of ultimately accumulating.” Michael Richardson, Georges Bataille. (New York: Routledge, 2005), 79. |

| 21. | ☝︎ | “Individual genius is not the origin of culture, as the tenacious myth of the originator without communities would have it. These communities too need to happen, especially in the gray areas, like rehearsal spaces. According to a liberal view on culture, ‘culture’ is something free floating – culture doesn’t need to happen and it doesn’t need community.” Samira Ariadad and Rasmus Fleischer, “Att göra gemensamma rum”, Brand, No. 1 (2010), 44–6. Accessed July 7, 2016, www.samhallsentreprenor.glokala.se/wp-content/uploads/Att_gora_gemensamma_rum.pdf. |

| 22. | ☝︎ | Banksy is another artist who activates urban spaces, who visually questions demarcations through his art, but also as reproduction and transaction. Sales of his paintings in Gaza and on the Israeli wall have been attempted on the art market. “Now I think that even if [Banksy] drew something very small – even a dot – people might cut down their walls and try to sell it.” Says Ayed Arafah from the Dheisha refugee camp in Bethlehem. Yolande Knell, “Gaza Family ‘Tricked’ into Selling Banksy Painting for $175”, BBC News, April 1, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-32139657. |

| 23. | ☝︎ | Full quote: “As the French anthropologist Marcel Mauss argues in his classical work The Gift from 1925, transactions of gifts and gifts in return – in welfare state terms, the taxation of work in exchange for risk spreading and social protection – contribute to social cohesion.” Hanna Bäckström, Johan Örestig, Erik Persson, “The EU Migrant Debate as Ideology”, Eurozine, June 15, 2016, 2. Accessed April 26, 2016, http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2016-06-15-orestig-en.html. |

| 24. | ☝︎ | Sven-Olof Wallenstein, “Kant, det sköna och det sublima”, Paletten, No. 4 (2015): 59. |

| 25. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 59. |

| 26. | ☝︎ | Marc Augé, Non-Places: An Introduction to Anthropology of Supermodernity, (New York: Verso, 1995), 101. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~jread2/Auge%20Non%20places.pdf. |

| 27. | ☝︎ | Ignasi de Solà-Morales, Catalan architect, historian and philosopher, coined the term terrain vague, applied to abandoned, obsolete and unproductive areas, with no clear definitions and limits. ——“Ignasi de Solà-Morales”, Wikipedia. Accessed July 26, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ignasi_de_Solà-Morales. ——“With the coining of the term Terrain Vague, Ignasi de Solà-Morales is interested in the form of absence in the contemporary metropolis. This interest focuses on abandoned areas, on obsolete and unproductive spaces and buildings, often undefined and without specific limits, places to which he applies the French term terrain vague. Regarding the generalized tendency to ‘reincorporate’ these places to the productive logic of the city by transforming them into reconstructed spaces, Solà-Morales insists on the value of their state of ruin and lack of productivity. Only in this way can these strange urban spaces manifest themselves as spaces of freedom that are an alternative to the lucrative reality prevailing in the late capitalist city. They represent an anonymous reality.” “Terrain Vague”, Atributos Urbanos. Accessed July 26, 2016, http://atributosurbanos.es/en/terms/terrain-vague. |

| 28. | ☝︎ | “A gradual advance beyond usual or acceptable limits: urban encroachment of habitat.” “Encroachment”, Oxford Dictionaries. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/encroachment. |

| 29. | ☝︎ | A synopsis of the project “A Place in Europe” can be found at www.ceciliaparsberg.com. |

| 30. | ☝︎ | I haven’t been able to get in since. The owners of the House won’t give permission despite my referring to research at the university. In one of my conversations with them to try to convince them to let me in so that I can film the project manager suddenly blurts out: “For the love of god I hope you’re not making a film about the bums on the site?” I regard this comment as interesting in this context and will leave it here for the reader to interpret. |

| 31. | ☝︎ | Hannah Arendt, “Thinking and Moral Considerations: A Lecture”, Social Research, Vol. 38, No. 3, (Autumn 1971), 430–1. Accessed July 29, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40970929. |

| 32. | ☝︎ | The sentence continues “In medieval philosophy this kind of thinking was called meditation, and the word should be heard as different from, even opposed to, contemplation.” Ibid., 431. |

| 33. | ☝︎ | Every year the Stockholm region grows by 35,000 inhabitants. The number comes from information about Värta and Hjorthagen where this place-non-place is located. “Vi bygger om Värtahamnen”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.stockholmshamnar.se/stockholm/vi-bygger-om-vartahamnen. |

| 34. | ☝︎ | Andrew Hewitt, “Choreography as a Way of Thinking about the Relationship of Aesthetics to Politics”, Documenta magazine project (2007). Accessed May 24, 2016, www.old.tkh-generator.net/en/openedsource/andrew-hewitt-choreography-a-way-thinking-about-relationship-aesthetics-politics-0. In the interview he talks about his book. Andrew Hewitt, Social Choreography: Ideology as Performance in Dance and Everyday Movement, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005). |

| 35. | ☝︎ | Here choreography is about how bodies dispose of their performativity spatially. |

| 36. | ☝︎ | Andrew Hewitt who isn’t a practitioner himself, he is Professor of Germanic Languages and Comparative Literature, stresses: “In a sense, my training in literary studies puts me at something of a disadvantage in talking about my ‘relation to performance studies’ because that relation, I think, might be better explicated from the other side of the dialogue, from the perspective of performance itself. It is certainly not my aim to offer prescriptions to performers, but to raise possibilities – perhaps in the realm of theory only – that they themselves might then articulate.” Hewitt, “Choreography as a Way of Thinking about the Relationship of Aesthetics to Politics”. |

| 37. | ☝︎ | The aesthetic as independent of the ethic, according to previous reasoning about image, see chapter 2 in particular. See also chapter 1.2 “Notes on the Text”, the passage on art activism. |

| 38. | ☝︎ | Hewitt, Social Choreography, 11. |