2.1 Is This an Image of a Human?

1.

What images does the begging person face as they kneel? What images am I facing when I do or don’t give to the begging person? How can I, as a professional image-maker, respond to these images?

Elfriede Jelinek writes, “Is this a piece of human that I see? Is this an image of a human? Is this a human from an image? Yes it is a human from an image. I know this! No I don’t.”1)Elfriede Jelinek, Rosamunde from Döden och Flickan I–V: Prinsessdramer, translated into Swedish by Ia Lind and Magnus Lindman, (Umeå: Atrium, 2011). German title: Der Tod und Das Mädchen I-V: Prinzessinendramen [Death and the Maiden I-V: Princess Plays]. The German original reads: “Ist das ein Stück Mensch, was ich da sehe? Ist es ein Bild von einem Menschen? Ist es ein Mensch von einem Bild? Ja, das ist ein Mensch von einem Bild. Den kenn ich doch! Nein, doch nicht.”

Who wants to be a human from an image? Does woman want to be a human from man’s image, the Swede a human from another nationality’s image, the Muslim a human from the Christian’s image and vice versa? The beggar does not want to be a human from the successful person’s image. But it isn’t that simple. The beggar doesn’t want to beg at all and the giver doesn’t want begging to exist – on this the beggar and the giver agree.

2.

We share an existence on the streets but we’re separated by a chasm – we don’t share it. How do I see the begging person? I ask a friend to take photos of me giving to begging people while we walk around central Stockholm for a day. I want to know what I look like; my attitude should be visible in my behavior, in the figure of my body. I also wonder what our figures look like in relation to each other.

A kneeling body in front of me, I can’t see his face, I see two hands, pressed together. His body says: I am begging. His hat on the ground says: I am begging you to give me money. My hand searches my pocket, but there are no coins in it so it stays in there, in the warmth, it’s cold today. My other hand finds some coins. I look at the figure below me and find it hard to fix my gaze on his red jacket, the red seems to blur; I try to focus: Red jacket, black hair, head bent. My eyes are hazy. I lean over to give him the coins, trying to see him as a whole figure. I stretch my arm toward his hat, my hand is almost under his head. I lean backward to keep from falling over him. The coin slips through my fingertips, he lifts his head ever so slightly, our eyes meet. We’re so close, but we’re in different worlds. One of my hands is still in my pocket, warm next to my body. My other arm dangles at my side, not knowing what to do. The man in front of me shifts slightly, back to his position. I wait for an eternity. I back out of the chasm. I notice him looking at my shoes, what is he thinking? What does he feel? Emptiness? Perhaps his stomach is empty; my head is. I keep walking down the street and notice that my eyes are still cloudy. I want to rub my eyes to clear them, but how can I see him clearly if can’t see what we’re doing?

2.2 What Images does the Giving face? & What Images does the Begging face?

1.

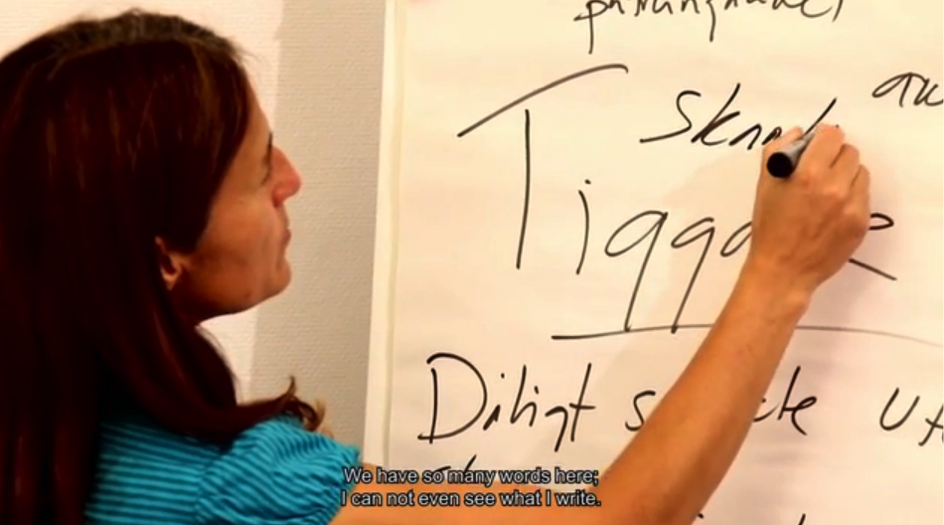

In the summer of 2011 I enlist a professional market researcher who performs a qualitative survey in which givers in Sweden share their views on those who beg and answer questions about how those who beg can become more successful as beggars in Sweden.2)A qualitative market survey attempts to shine a light on the underlying attitudes and values in a certain area. It also aims to give insight into various behaviors and emotions and how these can shape our choices and opinions. A qualitative survey looks for patterns in opinions and values. The questions posed pertain to why people think a certain way, why many choose a certain product and what the underlying reason is for the existence of a certain behavior. A qualitative survey doesn’t answer how many, what portion, or what percentage, think a certain way – these answers are delivered by quantitative surveys. In a qualitative survey a few people are interviewed and great care is taken that the people interviewed fill the criteria of interest to the survey, as opposed to a quantitative survey where representativeness is important. In a qualitative survey it’s only of interest to interview the people who are affected by the subject in question in one way or another. A qualitative survey is done using in-depth interviews or group discussions the length of which are adjusted according to need as is the number of people interviewed. A common time frame for an in-depth interview might be an hour and a group discussion might take two hours. This results in a film. Next I interview begging people who share their views on givers. This too results in a film. These two films are screened across from each other.

2.

What Images does the Giving face? This is the title of the first film (above left).

In my first encounter with the begging person I took their photo and broke my own honor code of not taking photos. I want to get images when I photograph, or at the very least be given them in some kind of transaction. In terms of mutual respect, I violated both my boundary and that of the other person. This prompted my investigation of my own position, my view of the person begging. I figured that if I saw them this way, perhaps others did too.

In consultation with the market researcher we decide that in order for the participants to talk about their feelings and reactions to begging, as well as to define what begging is, it’s necessary to have a number of photographs showing people begging. I find a few photos online, but it’s not enough. I need to go out on the streets and photograph.

The interaction with each person I photograph is unique, how our eyes meet, how I approach them, how I show them the camera, how I give money, how I ask for a photo. Often some kind of negotiation between us starts from a distance, across the urban space, with our respective body languages and gazes. Then, after just a few days and upward of 30 encounters I realize I don’t want to keep photographing them. I don’t feel comfortable no matter what I do. At each encounter I ask myself why I am about to photograph this person. I ask for a picture and I put something in their outstretched palm, it’s a decent negotiation, that’s not the problem.

An outstretched palm wants something. It can be read as an open question, not just to the giver, or to the person who passes the person begging, but to all of society, to the community. “Belonging together always also means being able to listen to one other.”3)Gadamer, 355. Hans-Georg Gadamer describes the discovery of a kind of belonging in the encounter, assuming the person addressed is open to the question and lets themself be addressed, while running the risk of facing what they don’t know. “A question places what is questioned in a particular perspective. When a question arises, it breaks open the being of the object, as it were. Hence the logos that explicates this opened-up being is the answer. Its sense lies in the sense of the question.”4)Gadamer, 356. Am I not looking for and trying to photograph the reasons for, and the consequences of, begging? The beggars are right there, to photograph them is to document – which is also important if something is to be documented – but the image stops at the act of depicting. What I see and lack is the participation of the person begging. The image-making stops at noting something, it lacks a dimension – the atmosphere surrounding this person. The photo seems to only confirm a stereotype, which is exactly what I am trying to break with, the generalization, the depicting. I try different angles and techniques, but for me the problem lies in the very taking of a photo. If I want to find out what images we face when we give, me making photos can’t be the main approach. None of those who beg have asked me to tell their story. I’m the one who has taken on the task of figuring out how to respond to the question posed to me: Do you want to give?

Michel Foucault talks about how he sees Belgian painter René Magritte’s (1898–1967) painting The Treachery of Images which depicts a pipe with the caption “Ceci n’est pas un pipe” [This is not a pipe]: “Suddenly I catch myself mixing up being and depicting as if they were one and the same, as if an image were what it depicts – and I realize that if I want to clearly differentiate between an image and what it depicts – and I should (as was inculcated by the logic of Port-Royal more than three hundred years ago) – I must now retract all those hypotheses I just formulated and multiply them by two.”5)Michel Foucault, Diskursernas kamp, texter i urval, eds. Thomas Götselius and Ulf Olsson, (Höör: Brutus Östlings bokförlag Symposion, 2008), 60. Title of the French original: Dits et Ecrits. In this case Foucault is talking about a painting, a case could be made that the same isn’t true of a photo. Furthermore the way we regard painting and photography has changed since Magritte painted his pipe in 1929, but I maintain that he is expressing the difference between an image and a visual. According to film critic Serge Daney this is a necessary distinction: “So I call ‘image’ what still holds out against an experience of vision and of the ‘visual’. The visual is the optical verification of a procedure of power (technological, political, advertising, or military power)”.6)Serge Daney, “Before and after the image”, Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, Vol. 21, (1999):1. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.home.earthlink.net/~steevee/Daney_before.html. He claims that there is “free play” in the image, much as there is in democracy. Incomplete parts, holes, and openings. In my attempts to photograph the person begging I discovered that I was confusing the beggar with the begging. I had mixed up being with depicting – with representation. In my first encounter I was upset by begging as an activity, not by the person doing the begging. I understand my distaste for asking people who beg if I can photograph them once it’s apparent to me that I want to investigate the reason why begging happens. And then there is the question of learning how other people reason when it comes to their giving or not giving and how they see the person who begs. Somehow I need to come up with thirty examples, so I process the photos I’ve already made and complete them with a few that I find online so that the pictures give as much variation as possible of various begging situations and positions.

In that moment – if I were to take a photo of what you look like, depict you, or if I were to make an image of how I experience you – the meaning of the image is determined. There is no value judgment in that. It’s a simple stating of fact.

3.

The recruitment agency hired by the market researcher has been asked to find twenty people who have given money at least once to a person begging on the street and who would consider doing it again. For two hours eight people talk about their approach to people who beg on the street. After this another group talks for two hours.

A qualitative market survey is usually done in a space with two rooms designed for that purpose. So too in this case: The talks are held in one room, led by the market researcher. In an adjacent room the client – I – sit behind a one-way mirror looking at the participants.

Eva, the market researcher, had explained that what she unearths in her market research, specifically, is people’s values – their feelings about a product, or a service, feelings connected to the function of a product or a service. She then consolidates these and the company translates them into images in its marketing of a product. Erik Pauser filmed the market survey using three cameras to capture the entire group, as well as close-ups of each participant. In addition the space had an overview camera, intended to capture everything so that the market researcher could write up a report at the end of it.

4.

Eva has the participants talk about images that show various positions, expressions and gestures that people who beg assume and perform in order to get money. Behind the two-way mirror I see and hear people express their feelings: aggression, guilt, shame, a desire to include and embrace, faith, hope, melancholia, want, authoritarianism and powerlessness. Even if one does give, no one gives to everybody and excuses must be made to justify this. They all have to do with how to keep beggars at a distance. One strategy replaces another. High expectations are placed on the beggar in terms of sensitivity to circumstances. The view of the beggars is that they must “earn their keep”. They must somehow deserve the money they get from the person giving it.

A number of images of begging and people who beg emerge in the discussions.

– I also think that there are some, usually young people, who just sit there with a sign, “I’m hungry”, they smoke, read a paper, look at their cellphone. Usually they’re Roma. I’ve lived in Eastern Europe, I know them… Some people may think they’re just immigrants, but most of these people coming here from Eastern Europe, Romania, Slovakia, are Roma.

– Now that Romania has joined the EU it’s become easier for them to get here. […] I have Romanian friends who tell me these people are Romani.

– It’s very different if a well-kempt person comes up to me and says: “Hi, excuse me, I lost my wallet, it was stolen, I need to take the train.” That’s something I might believe. Possibly. The situation seems plausible. If a person who hasn’t had a bath in a long time, and smells bad tries the same story it’s not going to have the same impact.

– Gangs.

– It seems more organized, the person begging isn’t the one who gets to keep the money.

– They put the most broken-looking person out there, that’s the most effective.

– Exploitation, one suspects someone else is behind it. […] But the other kind of beggars that you see, the Swedish ones, who are a bit younger, maybe adults, about 25–30, tend to have addiction issues… In those cases I offer them an apple, which they don’t seem to want. My feeling is that I don’t want what I give to go to drugs or alcohol. ☞

Eva: So one shouldn’t support drugs or alcohol?

– No. Even if they’re addicts and that’s what they want, I don’t think that’s a problem you can solve, you can’t just keep topping up their funds. But it gets pretty interesting when you hand them an apple or a sandwich.

Eva: They don’t want your sandwich, is that it? How do you feel about that?

– It’s sad. It’s even sadder.

– Why do I never ask the beggars in the subway the question: “What do you need the money for. What’s your plan?” I could. But the thought never occurred to me, I just want to be rid of them quickly.7)At the time of this market survey it was less common that the begging people had signs explaining what they needed the money for. Over the years that followed there was an increase in the number of signs, often hand-written, though some had photos of children with printed text on them. I don’t even want to look at them. […] I excuse myself. They give me a guilty conscience. If I give to charity, to a cause I know and understand, that does my conscience some good.

The participants in the survey make the same mistake I did when I wanted to take the photo; they conflate the person begging with being what they do for a living. When they talk about what they think, feel, how they describe the images they have of those who beg, I also hear a lack of understanding, a gap, a silence – none of them have ever asked those who beg why they’ve ended up where they are, why they do what they do. They have the types of images that might be termed given, that occur when one person is the viewer of another. They talk based on the assumption that their money and their position have come to them solely through hard work in a just system, and it is only very rarely suggested that:

- The beggars may be begging due to the system being unjust.

- Their own affluence may have something to do with the system being unjust.

In no way do I mean to imply that these are bad, or evil people. I see myself in them. My own vision is often clouded by given images. Their words appear to be a distillate of – and supported by, permeated by – ideas and lines of thinking that circulate in the society we live in today. It’s violent.

5.

When the group discussions are done Eva gets the file from the overview camera, she listens to it as she writes up her report.8)This report is available in the archives. I get the report a few days later. It’s 36 pages long. In the report it emerges that a successful beggar:

- Is in a dire situation that is more or less temporary.

- Is active – gets something because they are doing something.

- Is relatively clean – nobody wants to be close to someone who is too dirty.

- Is “normal” – a person with “normal” clothes that one can identify with is easy to understand – and does not make the giver uncomfortable with strange or unusual rituals.

- Can offer a reason for being in said situation, or explain what the money is going to be used for.

These answers disqualify many of those who beg on the streets of Sweden. It is clear that beggars, in various ways, need to live up to the demands of “authenticity” that we, the potential benefactors, make. Different types of beggars are ranked in relation to that ideal.

I ask a colleague, Karin Green, who has been active in building a network in which immigrants are integrated into Swedish society – and thus is someone with experience in seeing, countering, and working through prejudice – to structure the footage before the editing of the film.

The editing process takes five months. During this time I prepare for the second film – in which begging people are interviewed.9) The film has English subtitles: Market research – which images is a person facing when giving – or not – to a person begging? (16 min.). Accessed April 12, 2016, https://vimeo.com/81892362. The market researcher’s report is available in the archive.

6.

What Images does the Begging face? Is the title of the second film (to the right in the photo at the beginning of this chapter).

While the market survey is being processed I decide to find out what some of those who beg are thinking, and how they’re treated on the streets of Sweden. With Ioana Cojocariu as my interpreter I ask twelve people who have come to Sweden through freedom of movement and who beg on the streets of Gothenburg if they want to participate in a half-hour paid interview.10)Ioana Cojocariu coordinated and interpreted the interviews we filmed with begging people who’d traveled to Gothenburg in Sweden in 2011. She also cut and translated the film. Ioana is an artist, see chapter 4.1 paragraph 8. Ioana is from Romania and at the time she was relatively new to Gothenburg, there to participate in the Valand Academy MFA Program in Photography. She had previously spoken with some of the Romanian people who beg and tried to help them in various ways. Gathering twelve people who wanted to tell their story on film turned out to be easy for her.11)The film has English subtitles: Interviews with begging EU citizens – which images is the begging person facing? (57:30 min.). Accessed April 12, 2016, https://vimeo.com/66966202. All interviews have been transcribed and are available in the site’s archives. They trusted Ioana and seemed to trust me too when I sat next to her behind my camera. We had lit a studio, the camera stood ready on its tripod, the lapel mike was laid out on the chair where the interviewees would sit. The others sat waiting on chairs along the wall and listened until it was their turn. This way they did not repeat each other’s answers, but rather complemented one another’s stories. Primarily I wanted them to talk about how they beg and how they are treated. I didn’t ask them (specifically) to talk about their circumstances, but apparently they were eager to talk about their situation and about why they beg. Ioana told me that they had been mainly been expecting questions about why they beg, not how they do it, and how they are treated. Some of them shook their heads when Ioana insisted on these questions “Swedes are not like the people we’ve met in other countries”, they said. “They are very kind, generous”. They also said that they’d had bad experiences: That social services had wanted to take a child, that someone had spat on them, that people had thrown money at them, or violated them in other ways. They also talk about their circumstances, what they wish for, so that the viewer gets an idea of their situation.

Two of the twelve appeared to have come only for the money, their answers were curt and uninspired, and their body language signaled a desire to get out of there as quickly as possible. These two interviews are not included in the film.

7.

Together these two films make up the installation What images does the giving face? & What images does the begging face?12)In 2012 I uploaded these films to a new (at the time) project blog www.tiggerisomyrke.se [www.beggingasaprofession.eu] that I managed as a Ph.D. student. The blog opened a public window on my work process. The viewer sits in the midst of this flow of images that are put into play in every encounter between giving and begging people on the street.

The plaque for the installation reads: “Through what eyes do I see the person who begs; which images are given in advance, and what images can I make of what I see? Through what eyes does the person begging see the giver?

We all carry unconscious mental images that are amalgams of elements from (national) cultures, structures, decision processes, and institutions, but many images are replaceable, they can be destroyed and new images can be created.”

When I’ve set up the film that consists of the market survey of givers across from the film showing the interviews with those who beg, it is not to position them as opposites engaged in a constant struggle. Rather it is about a dynamic process concerning how ideas play out with and against each other – a process situated in time and space, a documentary. The two films show the distance that exists, visualizes it. An alienation is taking place – it is benevolent but also unkind.

In this installation the viewer is the one who has the opportunity to challenge, destroy, open up space for new images, and possibly act. Does this mean that everything is up to the viewer? It can’t be. The question is reflected back at the creator of this set-up, it is a theme that runs through the dissertation.

8.

“Desire and its object are one and the same thing: the machine, as a machine of a machine. Desire is a machine, and the object of desire is another machine connected to it. Hence the product is something removed or deducted from the process of producing: between the act of producing and the product, something becomes detached, thus giving the vagabond, nomad subject a residuum.” 13)Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, transl. Robery Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000), 26. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.libcom.org/files/Anti-Oedipus.pdf.

——“Desire does not lack anything; it does not lack its object. It is, rather, the subject that is missing in desire, or desire that lacks a fixed subject; there is no fixed subject unless there is repression. Desire and its object are one and the same thing: the machine, as a machine of a machine. Desire is a machine, and the object of desire is another machine connected to it. Hence the product is something removed or deducted from the process of producing: between the act of producing and the product, something becomes detached, thus giving the vagabond, nomad subject a residuum.”

(Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari)

“How do you become a successful beggar in Sweden?”. Language isn’t the only thing that cracks in this sentence, the entire situation on the street does, for everyone involved. Civil society in Sweden has reacted strongly to the new reality in which people beg on the streets. Two main streams of desire have emerged: to forbid or to help. The danger is, as the above quote implies, that begging and giving is explained by explaining “the beggar”. “The beggar” is objectified and becomes the problem, and at times also “the solution”. My market survey of givers generated images of a number of desires. The privileged perspective served as its starting point – what images and attitudes about begging are in circulation among the givers.14)The market survey was done in July 2011 and the film was published in April 2013 at the same time as the interview film, which was made parallel to it. By expressing various strategies the “givers” attempt to control the emotions that are triggered in the encounter with those who beg. This way the giver’s self image is strengthened (or even created). These images matter in terms of investigating and trying to understand what’s going on. Three years later Erik Hanson describes a similar approach in his master’s thesis in cultural geography: “When it comes to research on begging as a social phenomenon, the studies have usually assumed two main purposes and perspectives. Either they’ve tried to understand, or convey the living conditions of those who beg in various societies, or how political decisions, systems, campaigns, legislation, and institutions affect the conditions for beggars in various ways. In other words, there is strikingly little research that assumes the perspective of the viewer, the civilian citizen who in their encounter with the beggar on the street is faced with the choice of either helping or denying the vulnerable person.”15)Erik Hansson, “Som att världen kommit hit, Stockholmares upplevelser av tiggeri våren 2014” (Master’s thesis in cultural geography, Stockholm University), 7.

——Further, on the same page Hansson writes: “The point of this thesis is to try to understand what ideas the majority culture is projecting on these marginalized and vulnerable people, i.e. to study certain mental processes that have social consequences.”

The gaze and images of the viewer are discussed widely in various critical theories in the context of artistic research and art works. A specific question that beset me – and that actually and practically always should beset me and others who work on similar projects involving vulnerable populations – is how I can operate without becoming part of what literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak describes as “the work of subject constitution mingling epistemic violence with the advancement of learning and civilization. And the subaltern woman will remain as mute as ever.”16)Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman. (New York: Routledge, 2013), 90.

9.

In July and August of 2012, one year after my market survey, artists and Ph.D. students Reich-Szyber staged Tiggarlördag & Persondesign [Beggar’s Saturday & Persondesign] along a commercial street in central Stockholm. Thirty-five people aged 17 to 73 participated. Each participant had a sign that stated exactly what they were begging for.17)The following description is from their project page: “Through ads in among others Metro and Situation Stockholm [a free daily paper, and a magazine sold by homeless people] we sought people who were willing to beg for something they felt that they needed (or wanted to give to others). The pay was 100 kronor/hour and one got to keep half of what one earned begging. The other half was to go to Persondesign. 35 people in the age [range] 17 to 73 years participated.” “Beggars Saturday & Persondesign”. Accessed April 27, 2016, http://reich-szyber.com/en/portfolio/beggars-saturday-persondesign/. “When we go over the information we’ve been given, it appears most effective to beg for something that seems palpable to the givers (a visit to the dentist, a winter jacket, a pair of shoes, a gift for grandma). Appearing to be a trustworthy, middle-aged, well-behaved man is good. Appearing to be a young, happy woman with a future ahead of her is also good. The two groups that faired worst were those whose begging message concerned homelessness or poverty. The ten beggars who got the least money over the longest time were older on average, more likely to be women, several ‘looked foreign’, or appeared to be down-and-out.” Reich and Szyber determined that it is more important that the parameters of the transaction are clear than that the begging person is in actual need – in the sense of being poor. So far Reich-Szyber’s investigative performance overlaps with my own. But the market survey revealed more nuance.18)The market researcher’s report. Other than what criteria the begging person should ideally fit, the report also explains why the givers are bothered if the above criteria aren’t met.

- The givers desire an equal situation.

- The givers don’t want to feel bothered and uncomfortable.

This is due to certain aspects of the way that beggars from abroad communicate being foreign to Swedish givers, such as:

- Using religious symbolism that doesn’t register, isn’t understood, or appreciated.

- Assuming a submissiveness that is experienced as negative or offensive.

- Using intrusive manners or looks to catch the attention and interest of the giver.

- In order for a donation to be possible, or for the giving to be experienced as a pleasant act, the giver wants to maintain respect for the beggar.

- Human dignity must never be questioned or gradated, also many of the givers feel that begging is a mutual relationship, between the person begging and the person giving.

The project blog that I’ve been writing since 2011 was called beggingasaprofession.eu, my intent in using that title was similar to that of Reich-Szyber. They were thinking in terms of “removing the stigma from begging and making it a job like any other. At the same time the business needs to turn a profit.” Could a begging person become “successful” in Sweden? They failed to turn a profit; The Beggars’ Saturday project ran up a loss of over 90 000 kronor. “The thought experiment in which a market-oriented business model is applied to phenomena like necessity and a plea for charity; to let the entrepreneurial mindset, so to speak, cover increasingly wide swaths of our relationships with each other may reveal something of our present time to all of us.”19)Reich-Szyber, “Beggars Saturday & Persondesign”. They speak of being complicit in and working within the system. A system where work is organized, effectivized, done for profit and in order to satiate needs in the consumer, even if these needs haven’t even existed before, a creation of need out of desire. There is a notion of “the rules of the game”, of “adaptation.” ☞

Four years later the financial economist and priest Stanislav Emirov, writes about playing down begging, seeing it as an independent business within the realm of wealth transfer and regulating its scope and character through licensing and continuous control.”20)Stanislav Emirov, Varför tigger romer?, (Stockholm: Karneval, 2016), 229. In Stockholm, where Emirov is an aid worker at the Calvinist church he, and his research team (which he claims knows more than anyone in Sweden about the problems of begging), has rated those who beg according to motivation on a scale from one to five and found that most of them are at level one: “[…] the beggar hates begging, only begs to support themself and their dependents – and they are prepared to stop as soon as he or she has a job or another source of income.”21)Ibid., 16. According to their calculations ones, twos, and threes make 80 kronor per day in 2014, that’s a decrease from the previous year. He has yet to meet a four or five who works in begging. A four leaves the door open for other business opportunities, while a five is “a beggar who is completely at peace with being a beggar. They beg despite the availability of other realistic means of support and would not quit, even if he or she were offered a regular – according to our Western standards – job with a normal salary.”22)Ibid., 16. Emirov searches for a long time, in the end he does find a five: Michel, who is 35 years old and lives in Paris, in a three-room apartment in Montmartre. In 2014 Emirov goes to Paris to meet Michel for the first time. “Imagine my surprise when a convertible silver Maserati pulled up in front of me […] the man was dressed in beige chinos and a striped tennis shirt and seemed well-kempt, cultivated and sympathetic.”23)Ibid., 153. Emirov is offered a ride and Michel buys him brunch. Emirov gets to study his begging technique as he begs on a street corner in Düsseldorf, he observes him at a distance, through binoculars, for six hours. “In total he made 73 euro and 12 cents in three hours.”24)Ibid., 178. Afterward they discuss how Michel did it. He says that location is the most important aspect, then the time of day – there needs to be a steady stream of people, but they mustn’t be too stressed, they need to have time to make eye contact. He continues to describe what Michel does, his hours and his income.25) “‘I never work 30 days a month’, Michel commented. ‘Only 25. A six-day workweek. Not eight hours a day either, more like six. That’s pure begging hours. One has to eat, change money, move about. But on the other hand I can get more givers per hour than 30. It could be 50 or 60, If the stream is good and I’m on it. The last time I worked in Stockholm I went home with almost 4,000 Euro after two weeks and in Gothenburg more than 7,000 Euro after five weeks. But that was a long time ago. Last year.’” His monthly income seems to be at least 50,000 Euro. Michel’s expenditures are high. Since he never begs in his hometown of Paris – someone might recognize him – he travels to a different city in Europe each week, he mentions Oslo, London, Istanbul, Luxembourg, medium-sized towns in Italy, Austria, and Switzerland. He either rents a room or lives with friends. Michel also owns a small apartment, a run-down one in a suburb where he repays his begging friends by letting them spend the night when they visit him, they don’t know about his other apartment. Both apartments in Paris are bought on installment (he can’t get a bank loan since he has no proof of income). He has a Maserati convertible, he often goes out to restaurants with his girlfriend and sends money back home to his family in Romania – in any case they don’t know how well off he is. The question is how Michel makes ends meet. “Many beggars nowadays do more than just begging” is one of Emirov’s headlines but it’s not clear if Michel also does other business. He says he will continue to beg despite leading a double life and longing for a normal life. The conversations with Michel that follow cover a number of different begging techniques – according to him some are many thousands of years old – such as tremors, disability ruses, signs, how to work with the media, it’s reminiscent of stories that intend to reveal magicians’ tricks.26)Emirov, 163–192.

Michel’s story thus provides one answer for how a person can become a successful beggar in Europe, or the world. However, among the fifty-odd people I’ve spoken to during the years 2011 to 2014 on the streets of Gothenburg and Stockholm, I haven’t met or heard of anyone even vaguely resembling Michel. Nor are there any quotes from recorded audio, images, or other documentation to prove Michel’s existence. Stanislav Emirov doesn’t let any of the other people he meets during his many years as an aid worker speak in the book – the ones who make 80 kronor a day. Nor does he speak to any givers.

In my market survey that investigated how you can become a successful beggar in Sweden by speaking with givers, I assumed that every business – legal or illegal uses marketing techniques. But why do I think it’s more okay for Coca Cola to use marketing tricks than for a beggar to do the same. Emirov does let Michel say: “The beggar’s lie to the giver serves an excuse for the lie the giver tells themself.”27)Ibid., 165. He further describes this lie: “They view their surroundings through the prism of their role as givers. They want to be givers to satiate their own emo- and ego desires. And in order to be givers they need to tell themselves that beggars beg out of financial necessity.”28)Ibid., 165. But that is an image that only one begging person – Michel, who doesn’t beg out of necessity – has of those who give, who have been generalized in this claim.

The story of Michel also falls into a different framework than mine. The book is called Why do the Roma Beg? Michel gets to serve as an example of how Roma have developed begging as an art form to survive inside their own culture next to “the majority culture”. He dismisses those Roma, such as Katarina Taikon and Soraya Post, who have advocated for their civil rights, as being assimilated. Emirov ends by saying that nobody speaks to the Roma who beg and that policy aimed at assimilation is not the answer.29)There is a discussion of Roma in chapter 5.2. It does seem like he wants to speak to but I question both how he does it and what his intentions are.

10.

Spivak challenges the self-image of Western reason, bringing my own challenge of my self-image to my mind. As a doctoral student and subject-constituting artist carrying out a project with people who beg, I also inhabit the position of giver. “In seeking to learn to speak to (rather than listen to or speak for) the historically muted subject of the subaltern woman, the postcolonial intellectual must systematically unlearn her female privilege.”30)Spivak, 91. The quote is followed by the sentence: “This systemic unlearning involves learning to critique postcolonial discourse with the best tools it can provide and not simply substituting the lost figure of the colonized.” Unlearning doesn’t merely mean exchanging one image for another, it isn’t until the interviews with the begging people are shown across from the market survey that any kind of critique and reflection of these images of desire can take place. One could describe the installation as creating a space – for the viewer – to understand more about what conditions exist to grasp what takes place between the giving and the begging. The normative images of both those who are expected to give, as well as of those who beg must be renegotiated and reformulated, but the discussion must also deal with the position in society where these images are created.

When the film of the market survey and the film with the interviews are set up as an installation, the viewer sits in the midst of the image stream of social and sociopolitical processes. In a sort of mutual act, even if the position of one is forced by necessity and the position of the other – which is normative in the relationship – is given out of charity.

The beggar reveals that we’re pretending that everything is fine.

Staged Work:

( film installation for a room )

&

What Images

does the Giving face?

( 16:05 min )

What Images

does the Begging face?

( 57:23 min )

2.3 On Seeing Images

1.

Between 1999 and 2001 I worked in South Africa. During one of these projects, which lasted for two months, I lived in Soweto. I only saw two other light-skinned people while I was there, one was an albino black South African and another a white boss at a temporary roadwork project. I remember it well because I was so surprised, they stood out – I couldn’t see myself. A new political day had dawned in South Africa, attitudes and motivations had changed, conditions hade improved slightly, and there was a vision of other positions being possible. The images of the townships – that had been constantly transmitted as black and white photographs of violence, suffering, and uprisings – had been etched into my cornea and become mental images. The people I stayed with said: “We wish more people would come and stay here so that ‘whities’ will stop being so scared of us.” They spoke of how they wished that the images constructed during the apartheid era would be broken down and new ones emerge, in cooperation.

To see images is an act. This is a thought and a practice that was founded in me during these projects in South Africa.

I came from Sweden, I was a visitor and a bystander – I saw what was happening in that place with other eyes, I was astonished by the differences there, what their norm had become and what mine was. It made no sense to me. I didn’t pick up my camera for a month, not until I knew what I wanted. I wanted to make photos based on mutuality – or at least an exchange. The way I put it was that I didn’t want to take photos – I didn’t want to stay solely in the position of the viewer – I wanted to get the image. I was searching for intimacy, because it is in those encounters that we share our internal images, the ones shaped by both the impressions we have of each other as well as of the social situation in which the encounter takes place. It may just as well be old images that become relevant, or new ones created then and there. We tell our stories because we want to tell them, because the situation, rather than our position, demands it. I began seeing my job as “developing” these images through various practices, and then activating the images, mediating them. I don’t own them and I can’t sell them unless we have an agreement. I ended up with a series of works that declared the social and political context in which they were created.

I wrestled – and still wrestle with – the question Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak phrases as follows: “How [does one] keep the ethnocentric Subject from establishing itself by selectively defining an Other. This is not a program for the Subject as such; rather it is a program for the benevolent Western intellectual.”31)Spivak, 87. She poses the question that a privileged person needs to ask themself in relation to someone who is not privileged, a question about the conditions for the negotiation of power. It is a question that pertains to how practice and theory are wielded. I needed to understand how and where these projects would be transmitted.

At the time I took a very critical stance to the art market, I couldn’t sign these projects as mine in a show. And my gallery on Östermalm, an upscale neighborhood in Stockholm, didn’t see how they could sell these works. Due to this we terminated our contract in 2000. Since then I have produced and transmitted my works by myself or in collaboration with others (sometimes even with curators). My time in South Africa changed me as well my work.

2.

One expression that’s often used about works like mine, including at times by the artists themselves, is “giving someone a voice”. Regardless of whether that’s a question or a declaration of intent nobody can give another person their voice, everybody has a voice. Though the right conditions need to exist, be provided, or invented.

Over the next six years I worked with a number of projects in the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza, now Palestine, the last being A Heart from Jenin. At the time I strongly doubted my ability to retell the events depicted in the film. Palestinian poet Kefah Fanni gave me a piece of advice that has stuck with me ever since. He said: “Cecilia, you can never speak for us, but you can give your view of what you see here.”

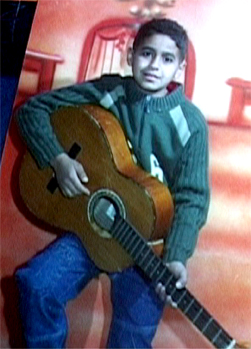

The film is about Ahmed, a Palestinian boy who lived in the Jenin refugee camp, on the West Bank. In November 2005 he was shot to death by an Israeli sniper. He was 12 years old. His parents decided to donate his heart to the other side of the wall, to Israel. A gift can effect change when there is someone on the other side willing to accept it. Samah is the name of the Israeli girl who now lives with Ahmed’s heart. For Ahmed’s parents their son lives on through the girl as a hope for peace with Israel.32)“A Heart from Jenin”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.ceciliaparsberg.se/a-heart-from/. ☞

Kefah’s advice made me appreciate my “outsider’s gaze”, I was accepted as someone who could contribute my presence. I depicted the empowerment that every person should feel that they have: the Palestinian family that gives a gift no politician can give and in doing so breaks isolation when they make contact with the Israeli family that accepts their gift. The film was mainly shown in the West, in the context in which I live. I felt I wanted to show this act here, because it was needed here. This film that is about the gift – despite distance, given images, framing – constitutes a background for my work on begging.

When I interviewed art curator and feminist Fataneh Farhani she commented: “International artists – I see it all the time – come to me with an idea that looks beautiful on paper, but the moment they see reality they rethink the project, because reality dictates facts.”33)Cecilia Parsberg, “Networking on the Wall”, Eurozine, (May 30, 2006). Accessed July 27, 2016, http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2006-05-30-parsberg-en.html. First published as: “Nätverkande på muren”, Glänta No. 1–2 (2006). Accessed July 26, 2016, www.eurozine.com/articles/2006-05-30-parsberg-sv.html.

During my stay on the West Bank I understood that given images – normative images – can be defended. “Clichés, stock phrases, adherence to conventional, standardized codes of expression and conduct have the socially recognized function of protecting us against reality, that is, against the claim on our thinking attention which all events and facts arouse by virtue of their existence. If we were responsive to this claim all the time, we would soon be exhausted; the difference in Eichmann was only that he clearly knew no such claim at all.”34)Hannah Arendt, “Thinking and Moral Considerations: A Lecture”, Social Research, Vol. 51, No. 1/2, Fifty Years of Social Research: Continental and Anglo-American Perspectives (Spring/Summer 1984), 8. Accessed July 29, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40970929. So writes Hanna Arendt. She describes common sense, as a sixth sense that is not mainly characterized by its sanity. She claims that a sensory world is made comprehensible together when we live under similar conditions. This is how common images arise.35)Arendt, 15. The common is necessary, the common evolves in a place and these (common) images must be respected. That doesn’t mean that they don’t also need to be constantly challenged. But how?

3.

To some extent I am caught in a framing – as is everyone – and this must be challenged. It is possible to be aware of given images and it’s also possible to become aware of the systems that images are made from and for, but never completely since it is the system I live in. All images are transmitted through some type of framing. One obvious example of framing is the photograph that was chosen as the best International News Image in the 2010 Swedish Picture of the Year awards. Paul Hansen took the photo after the earthquake on Haiti, one of the worst natural disasters in modern time with around 212,000 confirmed dead and about 300,000 injured.

In the image 15-year-old Fabienne Cherisma lies dead on a collapsed roof in the Haitian capital Port au Prince.36)Pea Nilsson, “Paul Hansen tog bilden på Fabienne,” Dagens Nyheter, March 18, 2011. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.dn.se/kultur-noje/paul-hansen-tog-bilden-av-fabienne. Afterward the image became a hot topic online – because of another image that captured the group of photographers that had gathered around Fabienne.

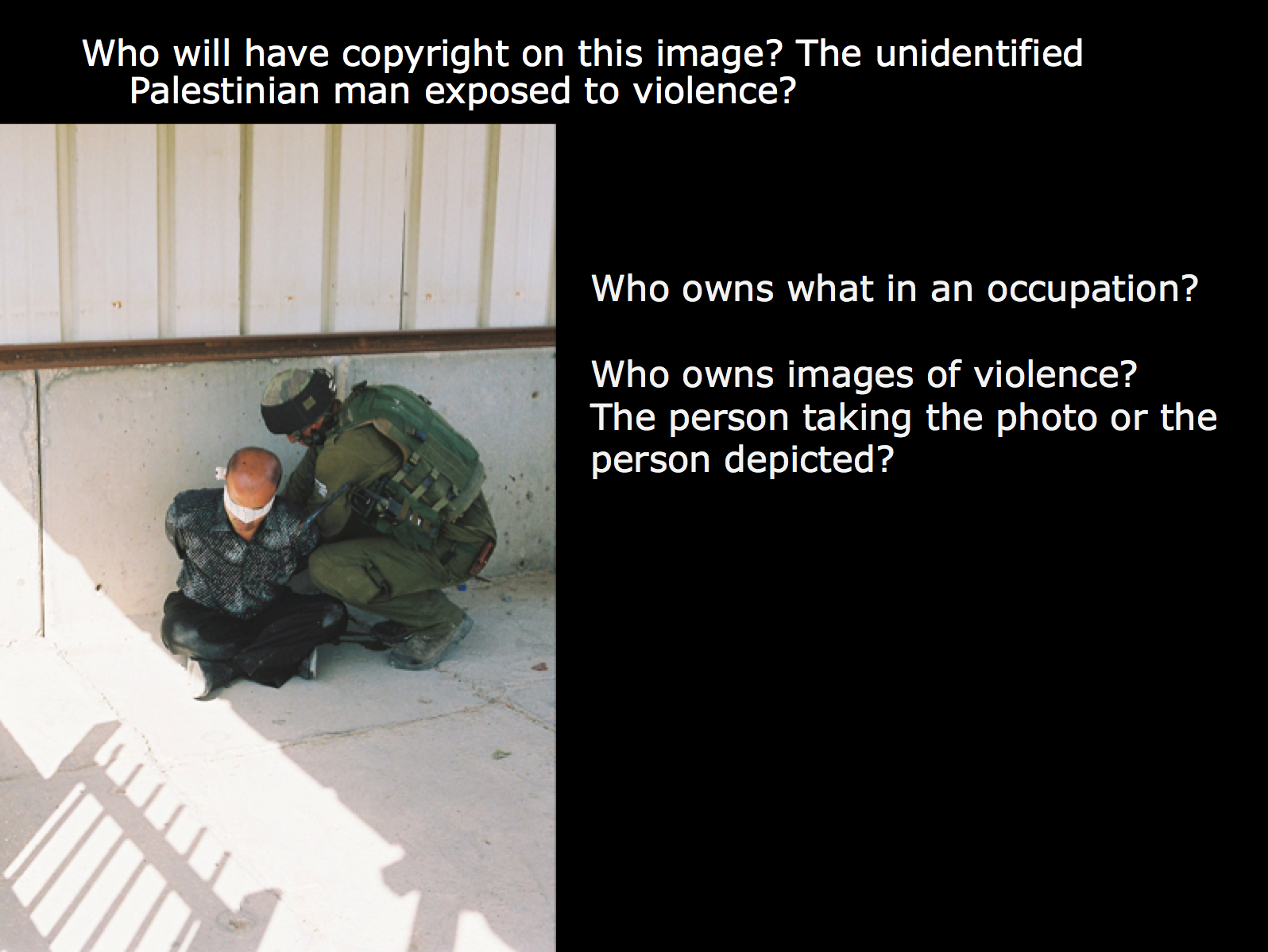

Nathan Weber’s photograph is another example of framing.37)Nathan Weber’s photo of photographers standing around Fabienne Cherisma. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.prisonphotography.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/cherisma-weber-nathan-photogs-img_7645.jpeg?w=432&h=288. It is a meta-photograph of a situation and it intends to illustrate how photos are taken. Media ethics, boundaries concerning image manipulation, whether bodies can be arranged in order to take a picture, representation, all these aspects also come into play in an artistic documentary practice (documentary methods that are transmitted in art spaces). Judith Butler writes the following about framing: “To learn to see the frame that blinds us to what we see is no easy matter. And if there is a critical role for visual culture during times of war it is precisely to thematize the forcible frame, the one that conducts the dehumanizing norm, that restricts what is perceivable, and, indeed, what can be.”38)Judith Butler, “Torture and the Ethics of Photography: Thinking with Sontag” in Frames of War: When is Life Grievable, (New York: Verso, 2016), 100. During the years that I worked in Palestinian and Israeli territories I was part of an international media discussion on mediation and the intention of the photographer. Israeli artist Bracha Ettinger brought the image below, containing a snapshot from an Israeli checkpoint on the West Bank, the discussion concerned questions that should always be relevant in situations in which power is wielded.

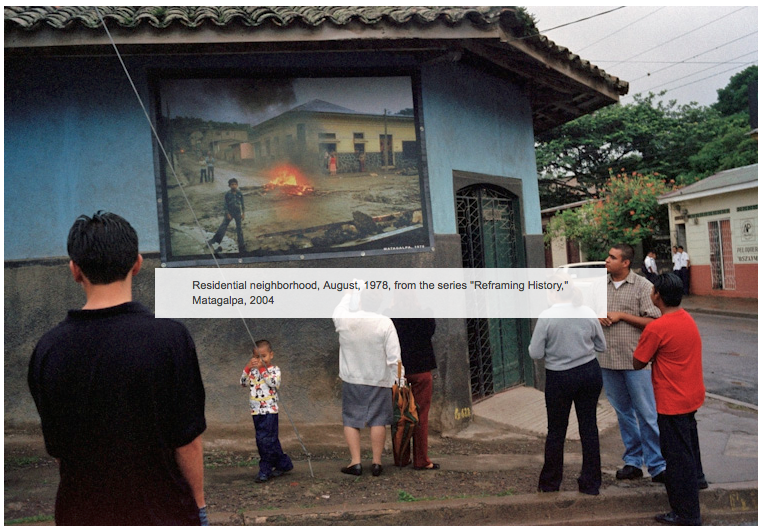

In 1978–9 photographer Susan Meiselas traveled to Nicaragua to photograph the uprising against the Somoza regime. While there she went through a change in how she viewed images, “It went beyond the question of ‘Why am I taking photographs?’ or ‘Who am I taking pictures for?’ It was a pivotal moment. It gradually became clear to me that as an American, I had a responsibility to know what the U.S. was doing in other countries.”39)Susan Meiselas “Nicaragua: Somosa Regime”. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.susanmeiselas.com/latin-america/nicaragua/#id=somoza_regime. She returns 25 years later and hangs 19 of these photographs “mural size” (about 2×3 meters), in the places in which they were photographed and ask people what they remember from this time. This results in a series of videos and audio recordings.40)Susan Meiselas “Nicaragua: Reframing History”. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.susanmeiselas.com/latin-america/nicaragua/#id=reframing-history. These stories recharge the photos in the installation Reframing History that has been shown as a part of various art exhibitions.41)Susan Meiselas “Nicaragua: Exhibitions”. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.susanmeiselas.com/latin-america/nicaragua/#id=exhibitions.

——In the exhibition “Crusading”, compiled by curator Jan-Erik Lundström for The Picture Museum in Umeå and Fotografins hus in Stockholm, Susan Meiselas installation was shown together with one of my installations: “both explore conflicts of power in a historical perspective.”. Accessed April 12, 2106, www.ceciliaparsberg.se/crusading/.

Framing is in the attitude, in the intention before the photograph is made in the moment of photographing it, in how it is transmitted, in the language, in the phrasing of the questions of the transmitter. “What is your view of the political situation in Greece?” the TV reporter asks. From that question we know that this is not about portraying a person, rather a contextual image is expected and the person responding is to give their perspective, their view, or whatever we should call it. A reporter could ask similar questions of the person begging, “What is your view of the political situation in Sweden?” But the reporters don’t, they ask other questions. They ask questions regarding the concrete situation of those who beg, their home life, health, ethnicity, studies, if they’re organized and at times with an undertone that implies that organization seems criminal in nature. Questions that would touch on success and creativity aren’t asked either, the reporter’s questions stay within a certain frame. This way the answer – the image that is given – is prevented from falling outside of this frame. It is the framing of the privileged. The requests from those who beg also stay within a certain frame. “Hey, a krona please?” There is an expectation put on the other. This expectation – which goes both ways, those who are expected to give and those who are expected to receive, risks becoming a frozen positioning of a viewer. The assumption is that we can’t understand each other.

4.

Filmmaker Werner Herzog is about to show a clip from his film Into the Abyss in a master class lecture at the film festival in Locarno. He tells the story of an interview with a key figure that he only got 40 minutes with. “He has to be broken up, watch this film clip.” We see pastor Richard Lopez in front of a field of memorial crosses, this is the cemetery of the State of Texas and this is where those sentenced to death are buried. Richard Lopez gives a brief account of how he assists the person on death row until their last breath. Herzog then asks what the pastor does to recover from his duties, because it must be difficult, and the priest tells him that he plays golf, his voice lightens up; he gets personal. There are lots of squirrels on the golf course, he says. Herzog asks “Please tell me about an encounter with a squirrel.” The man eagerly tells of a time when he was close to running over a squirrel, but managed to stop the car. “Life is precious”, he says. And suddenly he starts to cry, he can’t maintain the façade – he returns to the mission he’s on his way to and says: “I cannot stop the process for them. But I wish I could. ”The camera lingers for a long time on the man, now filled with sorrow. Herzog comments on this event: “All of a sudden we look deeply into his heart. […] I don’t know how I got there but, eh, you see how he started to get a bit mellow but regained his composure and you have to have the wisdom of a snake, you have to be coiled up, just wait and let him speak and you have to strike at the right moment with the right venom, right question, do the right move.” Herzog speaks of getting the story that transcends the lens, or catching, enticing, this image. “That’s something I cannot teach you and neither can a film school. You should always find a way to look deep into someone.” In this transaction the filmmaker is after the images and the stories – Herzog claims that cinema verité is a chimera, even if the filmmaker tries to be a fly on the wall, the filmmaker will affect the course of events – an ethical negotiation takes place. In some cases the ethics are subordinate to, in others they are above the aesthetics.

5.

My starting point for this project has been my experience of a non-encounter on a street, in Sweden where I live. I want to investigate and examine this distance, approach it: Is a renegotiation of the space between us possible, so that the images that both create and maintain the distance can be destroyed, renegotiated – so that new ones can be made? The problem is that there are already many images in the way.

6.

A year after the publication of Susan Sontag’s 1993 book Regarding the Pain of Others Judith Butler began writing the essays that were published in 2009 as the book Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? In it she discusses Sontag’s book and among other things, the critique leveled at Sontag when she said that the photographs from Abu Ghraib were photos of “us”. Some felt that this claim “[…] again the kind of self-preoccupation that paradoxically and painfully took the place of a reflection on the suffering of others.” But what she asked was “whether the nature of the policies prosecuted by this administration, and the hierarchies deployed to carry them out makes such acts [of torture] likely. Considered in this light, the photographs are us.”42)Butler, 99.

In a similar way the begging and giving exists within an economic structure that develops hierarchies. The begging is about “us” in the sense that the action is a consequence of a certain hierarchy of power within a particular system. My project involves many people and ethical quandaries arise along every step of the working process in conjunction with the aesthetic choices. Distance and intimacy, viewing and interaction, constant negotiation over space takes place between us, situations in which designations, stories, and images emerge. How these become politically significant requires examples, and this project may possibly be such an example. To see images is an act.

Chapter 2: Images

Notes

| 1. | ☝︎ | Elfriede Jelinek, Rosamunde from Döden och Flickan I–V: Prinsessdramer, translated into Swedish by Ia Lind and Magnus Lindman, (Umeå: Atrium, 2011). German title: Der Tod und Das Mädchen I-V: Prinzessinendramen [Death and the Maiden I-V: Princess Plays]. The German original reads: “Ist das ein Stück Mensch, was ich da sehe? Ist es ein Bild von einem Menschen? Ist es ein Mensch von einem Bild? Ja, das ist ein Mensch von einem Bild. Den kenn ich doch! Nein, doch nicht.” |

| 2. | ☝︎ | A qualitative market survey attempts to shine a light on the underlying attitudes and values in a certain area. It also aims to give insight into various behaviors and emotions and how these can shape our choices and opinions. A qualitative survey looks for patterns in opinions and values. The questions posed pertain to why people think a certain way, why many choose a certain product and what the underlying reason is for the existence of a certain behavior. A qualitative survey doesn’t answer how many, what portion, or what percentage, think a certain way – these answers are delivered by quantitative surveys. In a qualitative survey a few people are interviewed and great care is taken that the people interviewed fill the criteria of interest to the survey, as opposed to a quantitative survey where representativeness is important. In a qualitative survey it’s only of interest to interview the people who are affected by the subject in question in one way or another. A qualitative survey is done using in-depth interviews or group discussions the length of which are adjusted according to need as is the number of people interviewed. A common time frame for an in-depth interview might be an hour and a group discussion might take two hours. |

| 3. | ☝︎ | Gadamer, 355. |

| 4. | ☝︎ | Gadamer, 356. |

| 5. | ☝︎ | Michel Foucault, Diskursernas kamp, texter i urval, eds. Thomas Götselius and Ulf Olsson, (Höör: Brutus Östlings bokförlag Symposion, 2008), 60. Title of the French original: Dits et Ecrits. |

| 6. | ☝︎ | Serge Daney, “Before and after the image”, Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, Vol. 21, (1999):1. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.home.earthlink.net/~steevee/Daney_before.html. |

| 7. | ☝︎ | At the time of this market survey it was less common that the begging people had signs explaining what they needed the money for. Over the years that followed there was an increase in the number of signs, often hand-written, though some had photos of children with printed text on them. |

| 8. | ☝︎ | This report is available in the archives. |

| 9. | ☝︎ | The film has English subtitles: Market research – which images is a person facing when giving – or not – to a person begging? (16 min.). Accessed April 12, 2016, https://vimeo.com/81892362. The market researcher’s report is available in the archive. |

| 10. | ☝︎ | Ioana Cojocariu coordinated and interpreted the interviews we filmed with begging people who’d traveled to Gothenburg in Sweden in 2011. She also cut and translated the film. Ioana is an artist, see chapter 4.1 paragraph 8. |

| 11. | ☝︎ | The film has English subtitles: Interviews with begging EU citizens – which images is the begging person facing? (57:30 min.). Accessed April 12, 2016, https://vimeo.com/66966202. All interviews have been transcribed and are available in the site’s archives. |

| 12. | ☝︎ | In 2012 I uploaded these films to a new (at the time) project blog www.tiggerisomyrke.se [www.beggingasaprofession.eu] that I managed as a Ph.D. student. The blog opened a public window on my work process. |

| 13. | ☝︎ | Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, transl. Robery Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2000), 26. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.libcom.org/files/Anti-Oedipus.pdf. ——“Desire does not lack anything; it does not lack its object. It is, rather, the subject that is missing in desire, or desire that lacks a fixed subject; there is no fixed subject unless there is repression. Desire and its object are one and the same thing: the machine, as a machine of a machine. Desire is a machine, and the object of desire is another machine connected to it. Hence the product is something removed or deducted from the process of producing: between the act of producing and the product, something becomes detached, thus giving the vagabond, nomad subject a residuum.” |

| 14. | ☝︎ | The market survey was done in July 2011 and the film was published in April 2013 at the same time as the interview film, which was made parallel to it. |

| 15. | ☝︎ | Erik Hansson, “Som att världen kommit hit, Stockholmares upplevelser av tiggeri våren 2014” (Master’s thesis in cultural geography, Stockholm University), 7. ——Further, on the same page Hansson writes: “The point of this thesis is to try to understand what ideas the majority culture is projecting on these marginalized and vulnerable people, i.e. to study certain mental processes that have social consequences.” |

| 16. | ☝︎ | Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory: A Reader, eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman. (New York: Routledge, 2013), 90. |

| 17. | ☝︎ | The following description is from their project page: “Through ads in among others Metro and Situation Stockholm [a free daily paper, and a magazine sold by homeless people] we sought people who were willing to beg for something they felt that they needed (or wanted to give to others). The pay was 100 kronor/hour and one got to keep half of what one earned begging. The other half was to go to Persondesign. 35 people in the age [range] 17 to 73 years participated.” “Beggars Saturday & Persondesign”. Accessed April 27, 2016, http://reich-szyber.com/en/portfolio/beggars-saturday-persondesign/. |

| 18. | ☝︎ | The market researcher’s report. |

| 19. | ☝︎ | Reich-Szyber, “Beggars Saturday & Persondesign”. |

| 20. | ☝︎ | Stanislav Emirov, Varför tigger romer?, (Stockholm: Karneval, 2016), 229. |

| 21, 22. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 16. |

| 23. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 153. |

| 24. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 178. |

| 25. | ☝︎ | “‘I never work 30 days a month’, Michel commented. ‘Only 25. A six-day workweek. Not eight hours a day either, more like six. That’s pure begging hours. One has to eat, change money, move about. But on the other hand I can get more givers per hour than 30. It could be 50 or 60, If the stream is good and I’m on it. The last time I worked in Stockholm I went home with almost 4,000 Euro after two weeks and in Gothenburg more than 7,000 Euro after five weeks. But that was a long time ago. Last year.’” His monthly income seems to be at least 50,000 Euro. Michel’s expenditures are high. Since he never begs in his hometown of Paris – someone might recognize him – he travels to a different city in Europe each week, he mentions Oslo, London, Istanbul, Luxembourg, medium-sized towns in Italy, Austria, and Switzerland. He either rents a room or lives with friends. Michel also owns a small apartment, a run-down one in a suburb where he repays his begging friends by letting them spend the night when they visit him, they don’t know about his other apartment. Both apartments in Paris are bought on installment (he can’t get a bank loan since he has no proof of income). He has a Maserati convertible, he often goes out to restaurants with his girlfriend and sends money back home to his family in Romania – in any case they don’t know how well off he is. The question is how Michel makes ends meet. “Many beggars nowadays do more than just begging” is one of Emirov’s headlines but it’s not clear if Michel also does other business. He says he will continue to beg despite leading a double life and longing for a normal life. |

| 26. | ☝︎ | Emirov, 163–192. |

| 27, 28. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 165. |

| 29. | ☝︎ | There is a discussion of Roma in chapter 5.2. |

| 30. | ☝︎ | Spivak, 91. The quote is followed by the sentence: “This systemic unlearning involves learning to critique postcolonial discourse with the best tools it can provide and not simply substituting the lost figure of the colonized.” |

| 31. | ☝︎ | Spivak, 87. |

| 32. | ☝︎ | “A Heart from Jenin”. Accessed July 26, 2016, www.ceciliaparsberg.se/a-heart-from/. |

| 33. | ☝︎ | Cecilia Parsberg, “Networking on the Wall”, Eurozine, (May 30, 2006). Accessed July 27, 2016, http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2006-05-30-parsberg-en.html. First published as: “Nätverkande på muren”, Glänta No. 1–2 (2006). Accessed July 26, 2016, www.eurozine.com/articles/2006-05-30-parsberg-sv.html. |

| 34. | ☝︎ | Hannah Arendt, “Thinking and Moral Considerations: A Lecture”, Social Research, Vol. 51, No. 1/2, Fifty Years of Social Research: Continental and Anglo-American Perspectives (Spring/Summer 1984), 8. Accessed July 29, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40970929. |

| 35. | ☝︎ | Arendt, 15. |

| 36. | ☝︎ | Pea Nilsson, “Paul Hansen tog bilden på Fabienne,” Dagens Nyheter, March 18, 2011. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.dn.se/kultur-noje/paul-hansen-tog-bilden-av-fabienne. |

| 37. | ☝︎ | Nathan Weber’s photo of photographers standing around Fabienne Cherisma. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.prisonphotography.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/cherisma-weber-nathan-photogs-img_7645.jpeg?w=432&h=288. |

| 38. | ☝︎ | Judith Butler, “Torture and the Ethics of Photography: Thinking with Sontag” in Frames of War: When is Life Grievable, (New York: Verso, 2016), 100. |

| 39. | ☝︎ | Susan Meiselas “Nicaragua: Somosa Regime”. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.susanmeiselas.com/latin-america/nicaragua/#id=somoza_regime. |

| 40. | ☝︎ | Susan Meiselas “Nicaragua: Reframing History”. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.susanmeiselas.com/latin-america/nicaragua/#id=reframing-history. |

| 41. | ☝︎ | Susan Meiselas “Nicaragua: Exhibitions”. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.susanmeiselas.com/latin-america/nicaragua/#id=exhibitions. ——In the exhibition “Crusading”, compiled by curator Jan-Erik Lundström for The Picture Museum in Umeå and Fotografins hus in Stockholm, Susan Meiselas installation was shown together with one of my installations: “both explore conflicts of power in a historical perspective.”. Accessed April 12, 2106, www.ceciliaparsberg.se/crusading/. |

| 42. | ☝︎ | Butler, 99. |