5.1 Private Business, Public Space

1.

My view can open me: I see them! If I can only see myself in them, then let me encounter the stranger in me. If this is true for me, maybe it is for you too?

Once again I want to engage in dialogue, make contact, and film. I decide to approach the begging people where they sit. It’s July 2013 and with Laura as an interpreter I film everybody who is begging on Götgatan in Stockholm. From one end of the long street to the other, from Slussen to Skanstull – where I live – we find twelve people begging: eleven Romanians and one Swede, who’ll speak to us. We also approach two people who won’t speak to us, who raise their hand when they see my camera and refuse, even after Laura explains our project to them. I’ve given Laura the following questions:

- How is business? Do you get any money?

- Is there anything special that makes people give more? (Like – do you talk to them, look at them, do you sit or stand, choose a particular place?)

- Do you know anyone who gets enough money?

- Do you know anyone who gets a lot of money?

- What makes her or him get money?

- Do you think begging could be considered a job?

- If so, in what way?

- If no, why not?

- Do you think that there are beggars who consider it business like any other business?

- Do you think it would be better that way?

- Would it be possible to have a business plan for a beggar?

- What’s your name?

I crouch in front of Laura to record the begging person. I have instructed Laura to keep to the questions and to translate the answers for me as they come. But it turns out that she can’t or doesn’t want to interrupt the conversation that moves intermittently between the reason they’re here, their homes in Romania, their life stories, and current occupation. I balance the camera on my knees and prepare for an interaction between the three of us, but soon find myself on the outside, isolated behind a lens as I try to interpret tones of voice and gestures. I view the begging person and Laura through the lens, frame them in regards to light, color, and surroundings. I depict.

There was no encounter with the begging. Laura was deeply shaken after the conversations, needed a cigarette, to stand and breathe for a while before she could give me a recap of what had been said. I didn’t make contact with them, nor was I in control of questions and answers. I’m still working through that material to find some answers.

2.

Laura visits my apartment a week later. These conversations have made me reconsider, she says and continues to describe her image of these people when she lived in Romania. When she first saw them here she dismissed them, but now that they’ve spoken with each other she is “touched” – she and I speak English with each other. She wants to continue, she wants to know more. On the subway, on our way out to Högdalen, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Stockholm, she tells me that she understands their codes, both things that they say and their gestures. This time we have other questions. After a greeting ceremony and an exchange of cigarettes Laura starts talking with them. This time she translates directly to me. I can’t film, but we get to record the sound. I hold the camera under my arm with the lens pointed down.

Laura: What do you think a Swedish person needs to understand about your situation, why is this happening?

George: I tell you what’s happening – people tend to follow each other like sheep. For example, I used to know some guys, they went to France with 60 Euro in their pocket (the plane ticket), they stayed there for two weeks, whatever they were doing, they came back home with 320 Euro in their pockets. People see this and what do they think – “Let’s go there too, it’s better, we could find work, make some money”… one after another…

L: How did you find this place and make it your home? Did you search for a long time?

[Young man]: We found it quite hard, but it’s a very good spot. We take this path through the forest and get out directly at the train station.

[Woman]: We live in these huts, what can we do…

L: And in winter?

[Group]: The same. Yes.

[Woman]: The rents are too expensive. How could we have that kind of money? We go and beg, the men search for work. They work as day laborers in constructions, pavement…

L: How is it in comparison to Romania?

[Woman]: It’s better. Don’t you know the situation in Romania? It’s become a laughingstock, good for nothing. Some can manage, but three-quarters of the Romanians are gone. In Romania we lost our jobs, we have nowhere to go, no work. You cannot even find hourly work, you could at least work with digging the ground before, at least it was something.

G: Don’t film me, I don’t want to spread rumors in Romania… YouTube… Maybe somebody sent you? … Actually it would be good for somebody to help us, speak for us, at least to help some of us to go back home, or give us work… I see they give work to others, Arabs for example, Moroccans, they bring them to social centers, give them homes, and us… They hear we’re Romanians – since we have a European visa and can come and leave whenever we want, they don’t give us any chance to get work. They’re very racist with us. Some Swedish people help us by giving us half a Euro or a Euro, something to eat, but it’s hopeless as long as the rest leave us aside, ignore us. ☞

[…] There’s a social center at Ropsten, if you go there to sleep, or usually I go there to take a shower, you ask if they have spare places and even if they do, you have to wait to be picked up by a sort of lottery system that I don’t understand. So they make me wait, even if I just want to take a shower, and you have to pay 1 Euro anyway. In one day, maybe they have seven free slots, but 50 people are waiting outside to be picked. They want to have as many people as possible lined up on the list, so they can ask for more funding, they’re using us because I don’t see any change, all the time they tell you the same thing – that they only have 21 beds in the whole place… Anyway, a lot of social centers opened but when they hear us talking Romanian they wave their hands at us as if to tell us “you’re waiting for nothing”. It’s difficult to be Romanian. The truth is there was a lot of Romanians before us, that caused a lot of problems, and we are put in the same pot, because we’re Romanians too. Do you think I enjoy living in these conditions? But now I have two children back home, I live in a social home there, don’t have anywhere else to go. The social home is 60 Euro per month and then there’s food. I cannot manage, I manage better being here. I take a shower once a week and go around all week, collecting bottles, I explore places, I beg. Sometimes I feel ashamed to do it, but I have no option really, when I’m thinking about my family. If I would find a job, I would stop this at an instant, if they would promise me 4… 5… 600 Euro, but to have a place to live, to be able to come home in the evening, take a shower, to live like a human being. […] I’ve been staying here during the winter too, making fire in a bucket. I’ve lived like this for five years now.

L: How did you end up in Sweden?

G: First time I came here, I followed the promise of work from a contact. I only worked for two days for some Englishmen, after that I remained on my own. I worked for two days, so I cannot say I didn’t get work… [laughs].

Once I met a young man in Bucharest, he graduated from financial studies, finished two faculties, and he came to Sweden through an address, listened to some rumors about some social help. I told him: “Listen to me, forget about this, you are better off back home, in Bucharest, considering your education and experience, you can find work there if you try” He didn’t want to listen to me, telling me there is someone who promised him work. Later I met him another time, he had a big bag of cans, when I looked into it only 20 were good. At one point I wanted to invite him to stay here in our huts with us. I searched for him but he was nowhere to be found…

A lot of us had work back home and lost our jobs. In Romania, if you want to get a place at ADP [city cleaners], the bribe is 100 Euro. And a cleaner earns 150 Euro, the first month you have to work for free, you have a three-month contract, meanwhile if they don’t like you, you’re out. The ones who pay remain there, but these people have no families and can afford to pay. There was a social center at Zinkensdamm. This guy [referring to a young man next to him] wants to go back home, he doesn’t have the money. I take him to the center and they tell him there are no more tickets… If you could help us and go with him, you can talk better than us. He can speak English but they still don’t pay attention to him.

L: Can I leave you my phone number to help him with the tickets?

[…]1)The audio recording is transcribed by the interpreter, Laura Chfiriuc and is partially reproduced here. The entire transcript can be found in the archives of the thesis website.

3.

One day while I’m having lunch with my best friend I suddenly burst into tears. He’s surprised and asks why. I try to pinpoint various causes but can’t come up with anything that feels true and hits the mark. He doesn’t understand and creates his own explanation having to do with X being mean to me. The next day I figure it out, it’s about the film recordings I did that week: Encounters with the people begging on Götgatan in Stockholm and in their encampments in Högdalen. The interpreter Laura and I did a lot of interviews, talked to people and tried to understand why they come to Sweden to beg, but above all: How do they envision success and how are they treated? Simply: How is it working out for them? What are they thinking and feeling? How are they acting? What does their existence look like? These recordings affected me deeply and made me look at my own life, made me feel the fear of the unknown, the dirty, the difficult, the miserable. Next to them I appeared incredibly successful, clean, well dressed – I didn’t feel guilt, it was something else, sorrow.

I’m faced with a system that – like most systems, or is it the same system the world over – causes people to resort to begging. The begging person is not what renders me powerless it’s not about being faced with the other, that’s not the main problem. When there’s an outstretched hand I see people give food, clothes, money, cans, gloves, strawberries… Grasping the totality of the situation is what overwhelms me, I can’t handle it.

Today I wanted to take her with me – the 25-year-old sitting there with her soft eyes – I want to include her in my society. But then she shows me a photo on her cellphone of her family, her child. I see her home, her context in Romania. I can’t “bring her into my society” – she has a home. I give her 50 kronor and leave, damn, damn, damn, fucking politicians – fix it! Why does this situation exist? Perhaps she’s the one who should “bring me” into her way of life?

4.

“Ban the beggars!” A conversation is happening over a couple of glasses of wine, a box of chocolates and strawberries one evening in August in a garden in Enskede just south of central Stockholm. Ok, but if so, how do we differentiate between begging and asking for help? Does that mean I can be reported for begging if I ask for a favor? What should the moral foundation of our society be? We’ve entered into a European treaty about a kind of “free” movement. Perhaps one should say: “Free the beggars!” instead. Mainly this is about thousands of begging people who exist in nearly every major city in Europe. It is about duress and about a locked situation that I and many with me are forced to participate in and perpetuate.

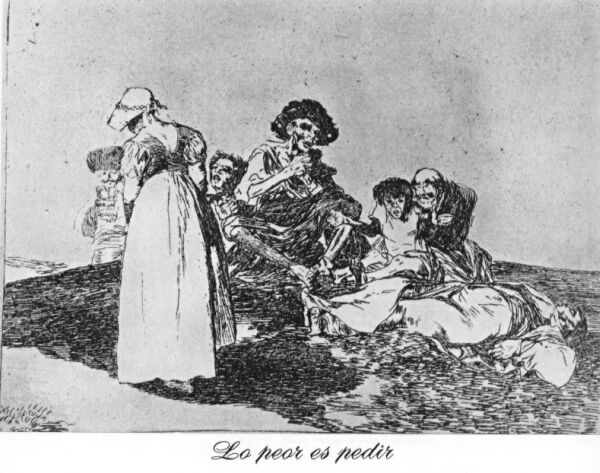

Arne Dahl’s crime novel Blindbock [blind-man’s-buff] is about begging in Europe, he has the main character, Hjelm say: “All of this is a sign of the times, we pass the beggars in the subway lightly, since we can ease our conscience by saying that in any case they’re controlled by a gang, a mafia… that soon we’ll see them in fancy restaurants with cellphones and credit cards, but all of this is an excuse, we’ve become immune to the suffering of others.”2)Arne Dahl, Blindbock, (Stockholm: Bonnier Audio, 2013), audio book, Ch. 3, 22:20 min.

In the morning paper Dagens Nyheter we can read that the beggar Petrina has reported herself a victim of human trafficking but the prosecutor claims that she can’t prove that she was deprived of her freedom in any other way than that she is poor, she wasn’t subject to force or to threats. She came her of her own free will, she got to keep her passport and was free to move from the camper to her begging spot as well as in and out of the country.3)Josefine Hökerberg, “Åklagaren om Petrina: Det är inte människohandel”, Dagens Nyheter, July 26, 2013. Accessed July 11, 2016, www.dn.se/sthlm/aklagaren-om-petrina-det-ar-inte-manniskohandel. “For something to be considered trafficking you must be deprived of your freedom”, says Christina Voigt at the international public prosecutor’s office. “She is, in a sense, since she is so impoverished. But that is not something you can charge someone else with in court.” And if it’s not human trafficking, then what is it? “They come here out of pure desperation”, says Christina Voigt. “It’s not human trafficking, it’s an EU problem. Since Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU their citizens have the right to move freely in Europe and many of those who come are very poor and dependent on those who arrange begging, or other activities such as picking berries.”4)Ibid. The thing that upsets a lot of people is that begging means not working, not making an honest living. How can one make money anyway? In the Swedish edition of The Human Condition translator Joachim Retzlaff writes: “Labor, in Arendt’s sense of the word, is characterized as a process with no end which is assigned meaning through productivity, but not by the products that are the outcome of the process.”5)Hannah Arendt, Människans Villkor, transl. Joachim Retzlaff, (Gothenburh: Daidalos, 1998), 17. What the beggars are doing is part of process with no end but it lacks apparent meaning because they’re not producing anything. And perhaps it is this ongoing apparently endless non-productivity that highlights the meaninglessness of our own existence to us consumers; we work to produce, to get a salary and to be able to consume – and when we’re out of money we need to work more to consume more.

The stated goal of productivity is progress, which has come to be equivalent with success in our society. But what does success look like for different people in their work and personal lives? What has meaning? The new begging also triggers discussions about giving.

5.

Political scientist Bo Rothstein published an op-ed piece in Dagens Nyheter on December 28, 2013.6)Bo Rothstein, “Därför bör vi göra det förbjudet att ge till tiggare”, December 28, 2013. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dn.se/debatt/darfor-bor-vi-gora-det-forbjudet-att-ge-till-tiggare. He proposes a new law, a ban on giving to beggars. He is convinced that a “ban on giving to panhandlers would force more comprehensive structural aid into being to assist this vulnerable group.” And he claims that: “a ban must be followed by some form of sanctions if it is to be at all effective, to punish these highly vulnerable, marginalized and obviously distressed people is at odds with our humanity and sense of justice. Yet it must be clear that further charity and continued panhandling can’t be the solution to these people’s social misery.”

I read the 129 comments on Rothstein’s article on the Dagens Nyheter website. One of them reads: “The beggar who asks for charity needs this in order to meet their fundamental human needs for the day, such as food. Isn’t it a bit harsh to stand by and watch the individual beggar starve, for the simple reason that I as a citizen of means think this the best way to catch the attention of politicians?” (masse: 09;42, December 28, 2013)

Is there any historical basis for necessity forcing justice into being when it comes to poverty? Or is that wishful thinking, an ideological construct? If giving becomes a crime, will society take responsibility for giving, or not? How should the line between philanthropy, solidarity, and welfare be drawn? These seem to be the questions that Rothstein wants to pose, or rather provoke. “One could also view the person who gives to panhandlers as someone who contributes to the social subjugation and humiliation of another person in order to fill some kind of need to feel righteous.” Rothstein wants to discuss giving, how it should work. As an activity begging presupposes a corresponding activity – giving. This is where it gets interesting, but unfortunately Rothstein gets overshadowed in the media, neither the public nor the media are interested in continuing that discussion.

How should the law – if such a proposal were to be enforced in practice – nail down what begging is? A line is drawn here between the giver and the person begging. What happens to individual responsibility for individual actions if the contact between the person giving and the person begging becomes regulated by law? Isn’t each person free to choose whom to give to? These lines of inquiry show how complex the situation is.

Further Rothstein writes: “Just as the person who ever so generously pays a sex worker (and perhaps treats them well) is still considered at fault, the person who contributes to the continued social humiliation that panhandling is must also be considered at fault.” When he draws a parallel to the ban on buying sexual favors, the law that was put in place in 1999, he doesn’t seem to distinguish between buying a sexual favor and giving to a begging person. This may seem a bit extreme, but perhaps this question must be asked, the question about the intent of the act of giving: What reasons drive a buyer of sex, what reasons drive one to give to a begging person? ☞

One must ask whether givers are perpetuating a power structure. It is also imperative to turn that question around and ask if it is possible to break such a power structure. My interviews with the beggars contain descriptions of various treatments from givers. In my conversations with givers they have a lot of feelings concerning the risk of becoming instrumental to a prevailing power structure. The agenda always contains both a structural question as well as a question of the individual’s freedom to act. How should they be dependent on each other? Is it ok to ban the individual’s choice to give and to help, for the higher purpose of a possible structural change to the system? Arne Dahl lets his EU-parliamentarian Marianne Barrière say: “But I am convinced that we have an inborn sense of justice, we immediately sense if we’ve done something morally wrong. There is an inner moral compass. […] Nobody understands what politics are about anymore, since there’s no society.”7)Dahl, Ch. 3, 23:40.

Susanna Alakoski describes politics as a craft and “democracy [as] a practice anchored in people’s daily social life.”8)Susanna Alakoski, Oktober i fattigsverige, (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 2012), 178. She reminds the reader that nobody is poor voluntarily and that poverty is a political condition.9)Ibid., 178. The 28 EU member states have a population of more than 500 million inhabitants. In 2013 Eurostat publishes information indicating that 115 million people are estimated to be at risk of poverty and social exclusion.10)In 2013 the number was 22.9%. Females 24% and Males 21.6%. See top row of the table: “European Union (28 countries)”, “People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by broad group of citizenship (population aged 18 and over)”, Demography report – 2015 edition, last updated July 14, 2016. Accessed April 27, 2016, http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_peps05&lang=en. Susanna Alakoski has a formula for how things may go if all responsibility is put on the individual to help their fellow human. “Charity = the state minus responsibility.”11)Alakoski, 151.

6.

Economist Anna Breman’s research shows that giving is a result both of altruistic behavior as well as people feeling good when they share.12)Economist Anna Breman wrote a book that focuses on frequent giving of relatively small sums to nonprofits. Anna Breman Forskning om filantropi: varför skänker vi bort pengar?, (Stockholm: EFI [The Economic Research Institute], 2008), 14. Private giving to charity in Sweden increased from 4.8 to 5.8 billion kronor a year from 2008 to 2013 (the statistics only concern bank accounts set up specifically to receive charitable donations so the actual numbers are likely far higher).13)Svensk insamlingskontroll investigates, oversees, and approves so-called “90-accounts” for organizations, nonprofits, and religious communities. Svensk Insamlingskontroll, “Statistics”. Accessed April 24, 2016, http://www.insamlingskontroll.se/en/pages/statistics. “The non-profit sector turned over about 140 billion kronor a year in Sweden and thus constitutes an important part of the national economy.”14)Breman, 60. “Economic research on altruism has intensified in later years […] but scientific study on the logic and practice of giving has been greatly neglected especially when it comes to more innovative and experimental research within the field of economics.”15)Breman, 59. This would involve for example finding other ways of giving, examining and perhaps breaking with existing power structures and not assuming the position of the spectator either on the street or in philanthropic activities. The system must be made visible. But how can this be done?

When Arne Dahl has Marianne Barrière claim that nobody knows what politics are about anymore, since society doesn’t exist, he brings concepts like community and solidarity to the fore. If everything is for sale, then why not Roma, why not people in general. Human trafficking, contemporary slavery, hits children the hardest since they’re not able to defend their rights. How do you become a successful beggar in Sweden? You sell your organs, your body, your sexual favors, for the success that keeping need at bay constitutes.

7.

In his work Enjoy Poverty16)Renzo Martens is an artist currently living and working Brussels, Amsterdam, and Kinshasa. Martens made a name for himself with his controversial documentaries Episode I (2003) and Episode III: Enjoy Poverty (2008). In 2010 Renzo Martens founded the Institute for Human Activities (IHA), which initiated a gentrification program in the Congolese rainforest.

——Episode III, also known as Enjoy Poverty is a 90-minute documentary film of Renzo Martens’ work in the Congo. In an epic journey the film establishes that images of poverty are the most lucrative export in the Congo, these generate more income than traditional exports such as gold, diamonds, or cacao. The project website reads: “Amidst ethnic war and relentless economic exploitation, Martens sets up an emancipation program that aims to teach the poor how to benefit from their biggest resource: poverty. Thus, Congolese photographers are encouraged to move on from development-hindering activities, such as photographing weddings and parties, and to start taking images of war and disaster.” But just as with the traditional exports, the humans who provide the raw material – “the poor being filmed, hardly benefit from it at all.” Renzo Martens, “Episode III”. Accessed August 1, 2016, http://www.renzomartens.com/episode3/film. artist Renzo Martens addresses the ways in which the philanthropic industry (nonprofit industry) perpetuates a colonial power structure. He also gives concrete, though ironic, suggestions for how impoverished people can change their situation, how their view and photos of their own situation could become part of the image production that currently lies in the hands of Western interests. Among other things the film shows his attempts to educate photographers in the Congo. His pedagogical attempts fail. In the film the attempts come across as questioning whether those who make money from publishing images really have any interest in changing the prevailing power structure. Martens stages a thesis, but when it comes to image production it seems doubtful that he really is pushing his thesis with, for example, the buyers at media companies and reportage magazines. So Martens isn’t very successful in changing the situation of the poor, but he does succeed in showing me and other people in his audience how documentation of others can perpetuate existing power structures despite the intent to educate; how the Congo is still in a colonial vise; and how complicated philanthropy is, as it can completely miss the mark and even hinder those it aims to help.

So how free are artists, journalists, and others who transmit images of people who are poor or vulnerable in other ways? Renzo Martens exposes how the aesthetics, the Western world’s image mediation of the poor person in the Third World, are part of the matrix. Martens’ film has sparked discussions in various art forums where people are alternately angered by his cynicism and admiring of the rhetoric that mirrors a colonial power structure. In my opinion he pinpoints an objectifying and colonial attitude by suggesting that the object/the other speak and claim the space to share their own narrative, rather than having an interpreter/photographer who describes and takes photos of them.

Martens says of his film Enjoy Poverty: “Most documentary films critique, or reveal, or show some outside phenomenon, like “‘oh this is bad,’ or ‘this is good’, or ‘this is tragic’. In this film, it is not the subject that is tragic, like poverty in Africa, it is the very way that the film deals with the subject that is as tragic. So that’s why it’s a piece of art, because it deals with its own presence, it deals with its own terms and conditions, it’s not a referential piece, it’s autoreferential.”17)This quote of Renzo Martens can be found in the discussion when Erik Pauser makes his second interjection. Maria Eriksson Baaz, Erik Pauser, Mats Rosengren, and Elin Wikström, “Enjoying poverty?”. Accessed April 12, 2016, http://app.samladeskrifter.se/article/12. Martens appears in the film himself, he films himself in a colonial khaki outfit, on a safari with porters behind him, he also has himself filmed as he teaches photography to a group of people. His point is that the film is art precisely because it deals with its own presence – how it was produced and the conditions for it. Martens also says: “My film is yet another industry that doesn’t help the poor.”18)The quote is in the epigraph of Ord & Bild, January 18, 2014. Accessed May 12, 2016, http://app.samladeskrifter.se/article/12. He is highly aware that he’s as stuck in the system as everybody else. With the film he “leaves it” to the viewer to identify with either him, in the role he plays in the film with fruitless attempts to find a solution and justice both for the poor people and for his own participation – or stand outside.

Watching Enjoy Poverty is frustrating, it’s challenging, because nobody can escape the system, there is no redemption. Part of my sense of powerlessness – that I’ve also experienced in several of my previous works – lies in this insight and the possibility I still have of exposing something of this matrix of aesthetics. Is it possible to see through the images that we base our discussions on? The images produced by the Westerner, by the Congolese, by perpetrators versus victims and other images that have become signifiers, stereotypes. ☞

Philosopher Mats Rosengren highlights the importance of going beyond the stereotypical images and trying to make an image of the system that produces them: “It is primarily this dynamic and self-perpetuating system that is exploitative – not the Westerners in and of themselves, even though they generally inhabit dominant positions within the political and financial realms. Martens showcases a clear and effective way to criticize the system from within: he also appears aware that such a criticism can never be articulated from a neutral place – obviously he and his film are also subsumed in this magma, with all the attendant ethical and political implications.”19)Eriksson Baaz, Pauser, Rosengren, Wikström, “Enjoying poverty?”. If knowledge isn’t linked to meaning and content, there is no point to it beyond self-generation. The same is true of art. Is it possible to criticize the system one participates in and if so how? Philosopher Boris Groys claims that the contradiction in which contemporary art activism is caught is positive: “First of all, only self-contradictory practices are true in the in a deeper sense of the word. And secondly, in our contemporary world, only art indicates the possibility of revolution as radical change beyond the horizon of our present desires and expectations.” He maintains that a political transformation cannot be achieved through the logic of the prevailing market economy and thus the change that an art activist is trying to engender is equally about the failure of this successful concept.20)Groys, On Art Activism, 19. See also chapter 1.2 “Notes on the Text” in the introduction to this thesis.

Renzo Martens has continued his work in the Congo, the Netherlands, and Belgium with the Institute for Human Activities21)“Institute for Human Activities”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.humanactivities.org.. The homepage reads: “The IHA asserts that even when art critically engages with global inequalities, it usually brings beauty, jobs, and opportunity to the places where such art is exhibited, discussed and sold.” At a lecture at IASPIS in October 2015 he brought two chocolate heads and said that he is investigating and wants to create a “critical art production that can fully deal with its own financial, economic and social terms and conditions.” The sculptures are made by the plantation workers Thomas Leba and Jeremy Magiala from Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantations Congolaises (CATPC). Renzo Martens holds up the sculptures and tells us: “They add their feelings and make these sculptures, as Congolese plantation workers cannot live off plantation labor, they will now live off critical engagement with plantation labor.” He maintains that this critique will be transmitted through the art created on site and through the seminars of the research institute.22)Renzo Martens, “News”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.renzomartens.com/news. His investigation is about finding “various ways to somehow bypass the conditions of critical artistic production and the capital accumulation associated with it.”23)“SEPTEMBER 2015 – Congolese artists, academics, and CATPC-members gather for ‘The Matter of Critique’ at the IHA research center in Congo. IHA is organizing the international conference series ‘The Matter of Critique’ to address the material conditions of critical art production. At the former Unilever-plantation they discussed art, global economic inequality, and the various ways to somehow bypass the conditions of critical artistic production and the capital accumulation associated with it in places like London and Venice.” Renzo Martens, “News”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.renzomartens.com/news. Thus art cannot escape the critical investigation that is necessary to knowledge production as well as to the system in which the art is created. His conclusion is that this critical investigation must take place in an encounter with the party oppressed by the same system, with those whose rights have been withdrawn, with those whose voices and emotional lives haven’t been acknowledged, not even in the realm of art.

5.2 To Be Free of an Image

1.

I have interviewed more than 40 people about begging, how they do it and how they’re treated. It’s become clear as we’ve spoken that many, though not all, of them are Roma, though ethnicity hasn’t been a central issue. The introduction to “Den nya utsattheten – Om EU-migranter och tiggeri”, Socialmedicinsk tidskrift [The new vulnerability – On EU migrants and begging] reads: “The majority of the impoverished EU citizens who are in the Nordic countries temporarily are Roma from the newest EU member states in the Balkans. Roma are highly vulnerable in many European nations.”25) “Den nya utsattheten – om EU-migranter och tiggeri”, Socialmedicinsk tidskrift, Vol. 92, No. 3 (2015): 251. Accessed May 6, 2016, http://socialmedicinsktidskrift.se/index.php/smt/issue/view/105.

On July 15, 2015 the EU parliament adopted a resolution proposed by Soraya Post that acknowledges anti-Gypsyism as a specific form of racism as well as the Romani Holocaust during World War II. She writes: “No Roma were heard as witnesses at the Nuremberg trials where the Nazis were prosecuted for their crimes. Nor did any Roma receive reparations for their suffering. […] This amounts to an acceptance of Nazi crimes against the Roma on the part of the majority culture, even as others were vindicated.” Roma were denied entry into Sweden between 1914 and 1959, among other things this meant that they couldn’t escape here during the Holocaust.26)“Genom den så kallade Zigenarutredningens betänkande [1954] betonas för första gången samhällets ansvar för de missförhållanden som romer lever under. Utredningen konstaterar att hat och fördomar har väglett och påverkat myndigheternas beslutsfattande. För första gången erkänns institutionaliserad rasism och diskriminering.” Quoted from the exhibition “Ett gott hem för alla”, photographs by Anna Riwkin och Björn Langhammer, The Modern Museum of Art, Stockholm, October 17, 2015–January 24, 2016. The ban on Roma immigration centered on the same perceived threats and hierarchical view of humanity that the sterilization laws were based on. “The persecution continues as long as I am denied my humanity by prejudiced people. In 1959 the Swedish authorities forced my mother to have an abortion when she was seven months pregnant and then sterilized her. She never saw the baby but the hospital staff told her it was a boy. There was no war, no racial propaganda, outside the hospital walls. We lived in the Swedish welfare state and my younger brother was murdered by the Swedish authorities. No camps necessary – just prejudice.”27)Soraya Post, “Vi måste göra romernas lidande till en del av vår historia”, Dagens Nyheter, July 29, 2015. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dn.se/kultur-noje/kulturdebatt/vi-maste-gora-romernas-lidande-till-en-del-av-var-historia. It wasn’t until 1982 that West Germany acknowledged that the Nazi regime murdered Roma due to their ethnicity.

Prejudice thrived silently in the welfare state, at the hearth, in the private sphere. Prejudice is built out of mental imagery. Ways of seeing can bring up images of others that we can’t see with our eyes. Through repetition these images become who the other is, it’s a way of making new myths – for better and for worse. In this case it has been expressed through prejudice. Which is shared by various political ideologies.

When does knowledge have meaning and when does knowledge cease to be knowledge if it no longer has meaning? When it acquires a layer of normativity – “hush, this is what we’ve always done!”

2.

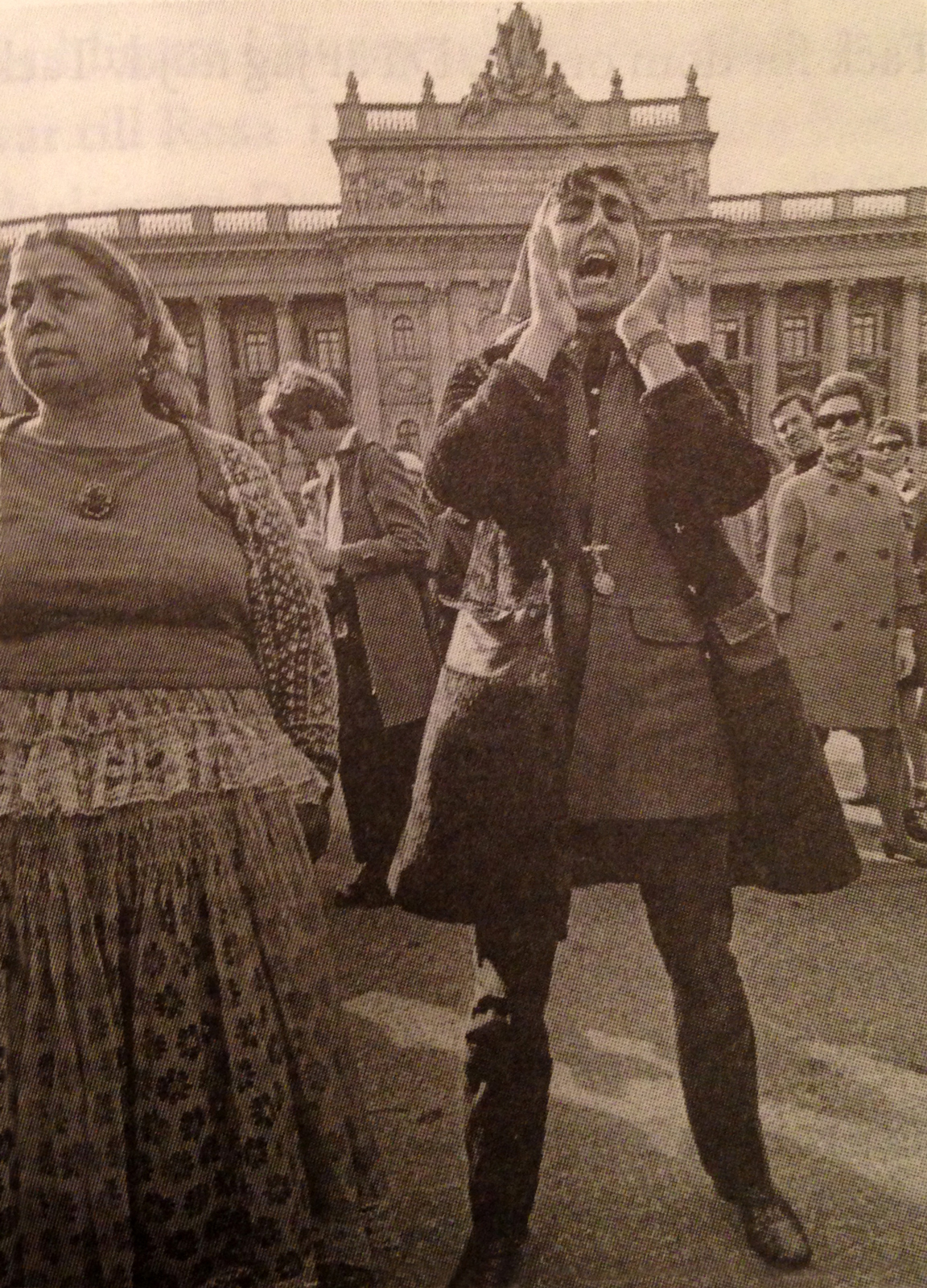

The author Katarina Taikon was Romani, she was born in a tent outside the Swedish town of Örebro in 1932. She made it her life’s work to change the view of Roma in Sweden: the prevailing, ingrained notion that they neither could nor wanted to live within the framework of modern society. Together with other activists and cultural figures she succeeded in evacuating the tent encampments that they lived in and pushed through the right to schooling. She never accused the welfare system, she never pinned the guilt on those who owned and had, her goal was simply to include everyone in Swedish society: In justice, in the law, and in the communal narrative, thoughts, images, ways of seeing and in the glance from one human to another on the street.

In 1968 activists and cultural workers – Katarina Taikon among others – write in the journal Zigenaren [The Gypsy], about “The racial biology of the 1920s, about Per Albin Hansson’s support for scientific racism, about the desire of Swedish authorities at the time to rid themselves of Roma, the immigration ban, Nazism in Germany, about the deportations and the group of Norwegian Roma who were denied entrance to Norway and later were found among the dead in the camps. The editors saw a direct connection between the more socially acceptable Nationalism and the Fascist crimes from the 1930s and onward.”28)Lawen Mohtadi, Den dag jag blir fri: En bok om Katarina Taikon, (Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, 2012), 158.

“The void that Katarina Taikon faced when she read about human rights is a void that’s persisted over the years. Since then many of us have stared into that void in a similar way: The gap between the idea that racism doesn’t exist in Sweden and our lived realities.”29)Karolina Ramqvist, “‘Zigenerska’ var början på en lång kamp”, Dagens Nyheter, December 25, 2015. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dn.se/dnbok/zigenerska-var-borjan-pa-en-lang-kamp. So writes Karolina Ramqvist. The tendency to make poor people in need of protection out to be greedy, spoiled Roma, can still be found today in the displacements that happen across European borders. ☞

The present situation of the Roma is a clear example of how immigration policy fails when industrialized nations produce refugees. The Roma have been excluded from immigration policy at two prior moments in history: After the Holocaust and after the wall came down, and once again now that the union has expanded. Thomas Hammarberg, a former Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights says that: “without changes in attitudes within the majority population, all programs aimed at improving the situation of the Roma people are bound to fail.”30)Commissioner for Human Rights, “Human rights of Roma and Travellers in Europe”, (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2012), 40. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.coe.int/t/commissioner/source/prems/prems79611_GBR_CouvHumanRightsOfRoma_WEB.pdf. In 2012 The Council of Europe published a report on the situation of the Roma in Europe.31)The work of the commissioners involves evaluating how human rights are respected in the member states and aiding in their implementation. The work of the commissioners includes maintaining a continuous dialogue with the governments and seeks to increase consciousness of and engagement in these rights. They publish their findings in reports and recommendations to the governments.

“The problem of statelessness and lack of personal documentation for thousands of Roma in Europe must be addressed with resolve, as these persons are often denied basic rights such as education, health care, social assistance and the right to vote.”32)“Human rights of Roma and Travellers in Europe”, 222. The purpose of the report is to show the link between the right to education, health care, housing, work and other fundamental freedoms. There are at present big differences between all of the EU nations, but generally speaking the situation is worse for Roma from the east. The report concludes that major advances have been made in the past two years toward the inclusion of Roma and that much remains to be done.33)“The years 2010 and 2011 saw major advances in the development of the European institutions’ explicit commitments to tackle the exclusion of Roma.” “Human rights of Roma and Travellers in Europe”, 222. In Sweden the Roma were recognized as a national minority in 2000. There are 10–12 million Roma around Europe, four out of five still live under the poverty line – except for in the Nordic countries.

“The survival issue is not a Third World issue; it is a global issue and an issue of globalization.” writes artist and theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha in Elsewhere, Within Here: Immigration, Refugeeism, and the Boundary Event.34)Trinh T. Minh-Ha, Elsewhere, Within Here: Immigration, Refugeeism and the Boundary Event. (New York: Routledge, 2011), 24. Parallel to the appeal to overhaul energy use and overconsumption in the world, to handle debt and environmental crises, people are uniting to reconcile and to pardon the people who have been excluded throughout history. In March 2014 the Swedish government published Den mörka och okända historien – Vitbok om övergrepp och kränkningar av romer under 1900-talet. [The Dark and Unknown History – White Paper on Abuse and Violations of Roma during the 20th Century.] The white paper is an acknowledgement and a starting point for strengthening the work on the human rights of Roma. “A survey of political motivations and measures during the first half of the 20th century shows that registrations, sterilizations, the removal of children from their parents, expulsion, and the refusal to include Roma in the population registry were motivated and executed based on the assumption that Roma were undesirables. These measures greatly complicated life for the Roma. Precisely this notion that Roma weren’t part of society also served as a motivation for taking measures directed at the group.”35)Regeringskansliet, Arbetsdepartementet, Den mörka och okända historien – Vitbok om övergrepp och kränkningar av romer under 1900-talet, Ds 2014:8, (Stockholm: Elanders Sverige AB, 2014). Accessed April 27, 2016, http://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/eaae9da200174a5faab2c8cd797936f1/den-morka-och-okända-historien—vitbok-om-overgrepp-och-kränkningar-av-romer-under-1900-talet-ds-20148. “It would be a mistake to view poverty among Roma as simply a social problem. Anti-Gypsyism is the root of their outsider status with all that follows. The deeply rooted prejudice against Roma is what fuels the discrimination”36)“Den nya utsattheten – om EU-migranter och tiggeri”, 265. according to Thomas Hammarberg. Katarina Taikon didn’t advocate assimilation, she demanded that: “Roma culture must be respected and space must be made for it in our country.” She used the term “integration”.37)From an article written in 1998 by Thomas Hammarberg, who at the time was ambassador of the Swedish Government on Humanitarian Affairs. The article is about Karl-Olov Arnstberg’s book, Svenskar och zigenare. En etnologisk studie av samspelet över en kulturell gräns.

——Thomas Hammarberg, “Tarvligt angrepp mot romer. Sanningen är att romerna har diskriminerats i Sverige, skriver Thomas Hammarberg”, Dagens Nyheter, October 2, 1998. Accessed April 27, 2016, http://www.dn.se/arkiv/kultur/debatt-tarvligt-angrepp-mot-romer-sanningen-ar-att-romerna-har.

3.

Culturally and socio-politically conditioned views, ways of seeing that create norms through systematic use – framing – become restrictions for what can be heard, read, seen, perceived, and known. In Judith Butler’s words: “This ‘not seeing’ in the midst of seeing, this not seeing is the condition of seeing, has become the visual norm, and it is that norm that is a national norm, one conducted by the photographic frame in the scene of torture. In this case the circulation of the image outside the scene of its production has broken up the mechanisms of disavowal, scattering grief and outrage in its wake.”38)Judith Butler, “Torture and the Ethics of Photography: Thinking with Sontag”, Frames of War, (New York: Verso 2009), 100. Butler is referring to the photos of torture taken at Abu Ghraib, one of Saddam Hussein’s infamous prisons in Baghdad which the U.S. Army in 2003 turned into their biggest prison camp in occupied Iraq. The images were taken by American soldiers as they humiliated and tortured Iraqi prisoners and were then spread across the world. These images have come to symbolize the war in Iraq. In a book by Philip Gourevitch, Lyndie England who appears in the photos says: “Photos don’t matter one way or another in a war. It’s all so stupid. I mean, why does the government think I’m the bad guy? The government puts the blame on me just because they can – just like a decoy.” (Philip Gourevitch and Errol Morris, Standard Operating Procedure: A War Story. (London: Picador, 2008) Philip Gourevitch collaborated with filmmaker Errol Morris who made hundreds of hours of interviews for his documentary Standard Operating Procedure, 2008. The white paper constitutes a vindication of the Roma. But it is only the beginning. It means that all citizens must change something, rephrase something, express something different verbally and physically. Without an acknowledgement that idea, that image doesn’t exist. Acknowledgement is given to someone. Acknowledgement is also the acceptance of someone.

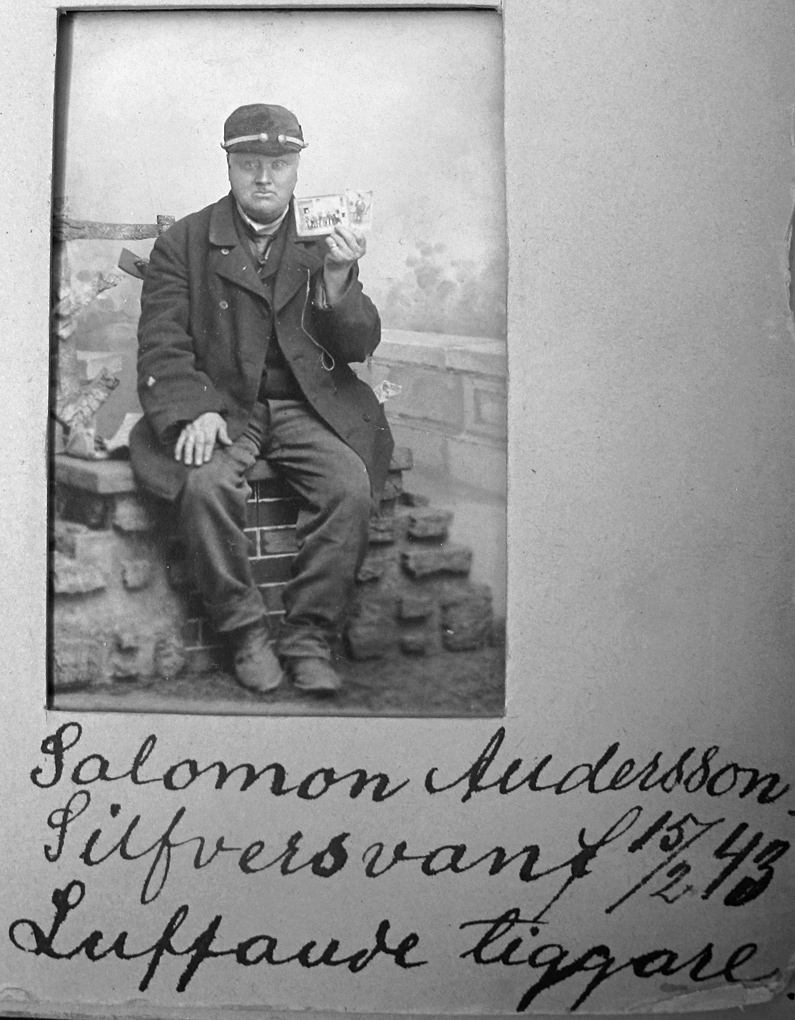

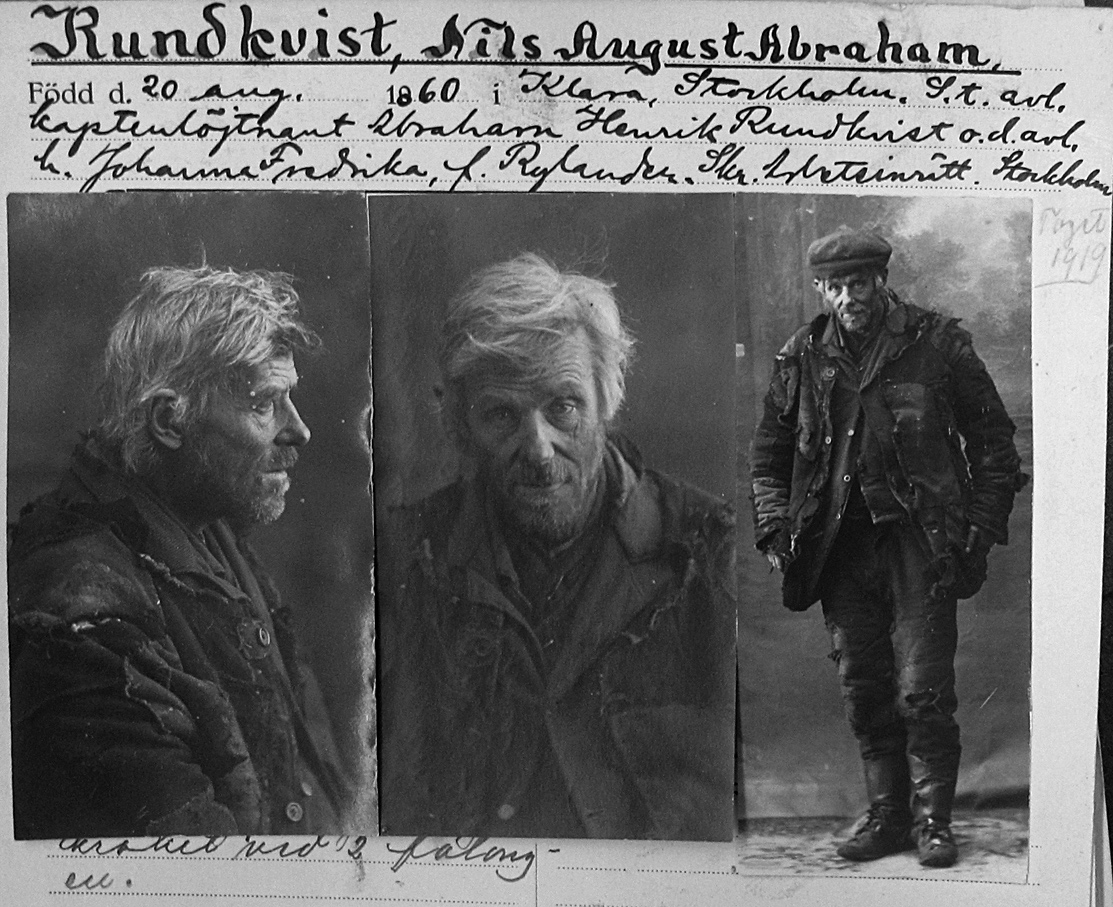

After the government published the white paper the phrase the Roma who come here to beg became more common to denote those who beg, as did variations thereof such as Romanian Roma who beg, or Roma migrants, or the begging Roma – despite the fact that Roma are not the only people begging on the streets.39)On Tuesday, March 25, 2014 the Government Offices of Sweden published the white paper that revealed 100 years of history filled with abuse and violations of Roma. I haven’t met one single Romani Swedish citizen who begs. A text on the history of begging in Sweden was published in 2015 on forskning.se: “In some municipalities we hear arguments reminiscent of those heard during the 19th century: Send the Roma home, they’re able-bodied and can work.” Thus Roma have become “the undeserving poor” according to Dick Harrison, professor of history at Lund University. He sees the attitudes of the majority culture as well as historical patterns repeat themselves.40)Lotta Nylander, “Tiggeri genom tiderna – ett social dilemma”, Forskning.se, April, 14, 2015. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.forskning.se/2015/04/14/tiggeri-genom-tiderna-ett-socialt-dilemma. In the book Stranger Shores J. M. Coetzee writes that our historical existence is a part of our present being, that it is inseparable. He claims that it is exactly the part of us that belongs to the past that we can’t fully understand because in order to do so we would need to understand ourselves both as “objects of historical forces” as well as “subjects of our own historical self-understanding”.41)“Historical understanding is understanding of the past as a shaping force upon the present. Insofar as that shaping force is tangibly felt upon our lives, historical understanding is part of the present. Our historical being is part of our present. It is this part of our present – namely the part that belongs to history – that we cannot fully understand, since it requires us to understand ourselves not only as objects of historical forces but as subjects of our own historical self-understanding.” J. M. Coetzee, Stranger Shores. Essays 1986-1999, (New York: Vintage, 2002), 15. We can’t understand ourselves in the present, but we can – based on what we do in the present – change our understanding of our historical self. We can confront our understanding of our historical self, in an encounter with the present.

I ask key figures in regular contact with people who are in Sweden begging what percentage of these people are Roma and about their view of that designation. My first contact, Victor Emanuel Chiorean, writes me an email: “If one is looking for exact statistics on what percentage of the beggars in Sweden are Romanian Roma, one will run into a couple of obstacles:

- Free movement makes demographic data difficult to parse.

- The individuals who allegedly beg are not registered in Sweden or in Romania, they simply leave and return when things get really dire. So there is no official statistic that investigates this. What we do have are samples attempted by various actors, among others the police and other authorities in Sweden.

- The demographic underreporting that the Romanian Romani populations constantly are up against. According to the official Romanian census there are about 500,000 Roma in Romania, while the EU, the European Council, and human rights organizations maintain that the population is more like 2,000,000. Which would indicate that they are underreported by 75 percent. The reason is difficult to pin down, but many Roma don’t want to identify themselves as such.” ☞

The artist and public intellectual Hans Caldaras is of Romani descent, he grew up leading a travelling life and started school at age 10. He writes me: “Many of the Romanians and Bulgarians who beg are Romani, but it is important to stress that some from countries like Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland aren’t Roma. It is worrisome to identify begging with Roma since this increases anti-Gypsyism and general antipathy toward Roma.”

A third contact, who was born in Hungary and grew up in Romania, explains to me over the phone that Romania and Hungary have many minorities who are discriminated against and ignorance makes it easier to call them all Roma. Rickard Klerfors, an economist from the organization Hjärta till Hjärta [Heart to Heart] writes that many of those who come here and beg are Roma, but not all.42)Hjärta till Hjärta [Heart to Heart] is one of 41 organizations in Romania with some link to Sweden, the rest are listed on their website: Hjärta till Hjärta, “Värdighet här, förändring där”, September 17, 2015. Accessed April 27, 2016, http://media.hjartatillhjarta.se/2015/03/RPT-Organisationer-i-RU-o-BIU-version-2.2.pdf.

An interview in Dagens Nyheter on February 10, 2015 reads: “She and the siblings who are with her in the workshop stress that they aren’t Roma, they are Rudari. A Christian ethnic group who do not speak Romani, but who the Romanian government counts as Roma. They live in the village of Crovu, five miles from Bucharest where the mother takes care of the children, while they try to make a living. ‘There are no jobs at home. I don’t have a job, neither does my husband and it is hard to sell spoons, since that doesn’t bring in much money. I only have four years of schooling and I have six children to support,’ says Aurelia Marin.”43)Jessica Ritzén, “Jag säljer hellre skedar än tigger utanför Coop”, Dagens Nyheter, February 11, 2015. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dn.se/sthlm/jag-saljer-hellre-skedar-an-tigger-utanfor-coop.

So it seems reasonable that the discussion of begging be associated with, but not conflated with, the situation of the Roma. Even if a majority of those who beg on the streets are Romanian Roma, and Roma are the largest minority in Europe, the designation the Roma who beg is very problematic, for several reasons: Because Roma in general are associated with begging and it strengthens prejudice against Roma and thus discrimination. If efforts are made to earmark money for Roma who beg and their children and non-Romani people who beg are singled out because of this, the latter would end up at the bottom of the hierarchy. Any categorization that strengthens one group risks marginalizing another.44)Racism can manifest in many different ways, it’s about mutual respect between people on the street and on all levels horizontally and vertically in society. Racism is an ethical phenomenon that has to do with organic solidarity (see text 5.3)

4.

Judith Butler suggests that “we” consider where the normative operates: “namely through norms that produce the idea of the human who is worthy of recognition and representation at all. […] In other words, what is the norm according to which the subject is produced who then becomes the presumptive ‘ground’ of normative debate.”45)Butler, Frames of War, 138. Only those who do the begging, or those who do the giving on the street can determine this norm. Özz Nujen jokes that Swedes say: “I’m not racist, but…” He maintains that nobody is completely free of racism, there is no neutral position. Trinh T. Minh-ha writes: “As human history substantiates, it sometimes takes a catastrophe, whether ‘natural’ or man-made, to pull us together across endless security walls and boundaries. (And yet…) Our massive drive for destruction could then find itself mirrored by an equally immense capacity for forgiveness and hope. […] However it is in the face-to-face with the impossible – the irreparable and the non-negotiable – that the possibility of forgiveness arises, […] For the debt of love knows no limit; what it requires exceeds all judicial logic and processes.”46)Minh-ha, 25.

5.

Europe, ask the Roma for forgiveness!

To see is to ask to look, to ask to receive an image.

6.

During the spring of 2013 a couple of conversations with those who beg were finally published in the media, and these images began to edge out the first images that had been produced on assumption and speculation.47)Josefine Hökerberg, “Resan till tiggarnas hemby blev en chock”, Dagens Nyheter, September 28, 2013. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dn.se/sthlm/resan-till-tiggarnas-hemby-blev-en-chock/. See also: “Frågor och svar. Tiggarna i Stockholm”, Dagens Nyheter, March 11, 2013, www.dn.se/arkiv/stockholm/fragor-och-svar-tiggarna-i-stockholm. Journalists Josefin Hökerberg and Roger Turesson interviewed some of the people begging in Stockholm, visited their encampment here, and went to the village of Malovinat in Romania to see how they lived in their hometown. They are poor, they organize best they can in order to help each other. According to these articles they make an average of 150 kronor a day, which is 4,000 kronor per month.48)Josefine Hökerberg, “Jag vill inte titta folk i ögonen och be”, Dagens Nyheter, May 30, 2013. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dn.se/arkiv/stockholm/jag-vill-inte-titta-folk-i-ogonen-och-be. See also: Josefine Hökerberg, “Florica Tudoricis lön: 186 kronor på en dag”, Dagens Nyheter, March 11, 2013. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dn.se/arkiv/stockholm/florica-tudoricis-lon-186-kronor-pa-en-dag. In Romania the minimum monthly wage is 2,500 kronor. Journalists are investigating those who beg because their readers are worried and wonder if they should give. Are those who beg truly deserving? It’s a good thing that media investigates – and compares – activities. Which needs does an activity respond to, take banking for instance? Are the demands of authenticity higher on those who beg, or as high as those made on those who sell advertising, for example? The activities that are investigated also indicate where the fears, the uncertainties, lie – in this case in the Swedish reading public.

7.

I bike to Högdalen, colloquially called “Highvalley”, and onward to Cyklopen, a cultural center which is being built by the nonprofit organization Kulturkampanjen (www.cyklopen.se). There I find Alvaro who curses the “gypsies” in the encampments a few hundred meters away because they steal his clothes, building materials, and chairs. He’s caught them red-handed inside Cyklopen. His burnt-out car is outside.

– They burned my car, and look at the cherry picker, which we need for our construction work, it was next to my car and got half burned too.

– But was it really they who burned your car, why would they do that? I ask. I understand why they would take clothes and building materials, but not why they would burn a car. Destruction is something else entirely.

He hesitates:

– Perhaps it was some youth who tried to…

I’ve just read Lawen Mohtadi’s recent book on the life of Katarina Taikon and am thinking how easy it is, when one is emotional, to blame everything that goes wrong on those one doesn’t have much contact with, those one doesn’t understand, those who are outside of the social system.

– They put up camp here three months ago. The entire forest is a sewer now. They don’t wash, they just dump their dirty clothes in a pile once they’re done with them. Send them away, Alvaro says, emphatically.

Lasse and I leave Alvaro and continue onto a bridge from which one of the encampments is visible, a trailer, three cars, people working on a car. We take another dirt path that leads to another larger encampment and start walking but we stop after 10 meters, we feel like we’re intruding on people’s private life. We turn around and walk toward the exit off the main road. A big rock blocks the entrance. A car turns off onto the gravel to get around the stone, a window is rolled down, someone bums cigarette and shows a begging sign. While we each roll a cigarette some other people come walking, they stop too and want a smoke. They’re Roma who’ve come from Spain. Suddenly Alvaro shows up on a bike, is curious, stops and starts speaking fluent Spanish. Some people pass in their cars and wave. Alvaro greets them with a friendly “Hola” and speaks to them a bit in Spanish. His animosity is gone.

– Survival, I tell Alvaro, who responds that all Roma ever think about is money, he’s lived with many of them, both in communities as well as in prison.

– That’s not true, is it? I read a book about Katarina Taikon. Swedish Roma and Travellers, haven’t had the same opportunities in terms of schooling and housing, and they’re obviously still affected by that. It takes time to wash away prejudice.

– I know several Taikons, Alvaro says. Have you lived here long?

– No, I live on Söder.

In that moment I feel like I’m almost apologizing for living where I do. But I go on:

– If you’re viewed as shit you become shit, unless you’re truly exceptional. Why should one expect more from a poor Romani person than from a person from Söder or Östermalm? Who among us can say that money isn’t “all we ever think about”, in the sense that we’re focused on making money, surely those with a lot of money do too, how else did they make all of it?

It smells bad outside the encampment where we’re standing, like sewage.

Do you know Harry? Alvaro asks Lasse.

– Yes, he’s a Finnish Roma, he was in prison for years and when he got out he asked all his friends if they would clean for him. I didn’t, but 50 kronor an hour was pretty good pay…

– They keep exchanging names and talk about people who’ve been to prison and others who’ve fallen into various types of addiction.

As I stand there I think about allemansrätten, the Swedish right of public access to the land, that once ensured the forest was everybody’s pantry, everybody’s right to the bare necessities. I tell Alvaro that what I’m most afraid of is exactly what he said: “If they don’t fit in, we’ll kick them out.” What do we do to ourselves when we say that? He smiles, looks me in the eye and says that he knows what I mean. He’s been testing me, my thoughts, knew who I was when he said that. I think about places I’ve spent a lot of time, the West Bank, Gaza, the townships of Soweto and Alexandra, and try to understand. People there live in a sort of shared economy and help each other with things like daycare and unemployment support, because there’s no other infrastructure. They have their own laws, their own judicial process outside of the national law… My head is spinning. Should I retreat to Söder and make art in a space designated for art, as I’ve been taught to do. Why should I meddle here, on site? What is my role as an artist? Am I making a living off people in misery? Lasse says he’s never seen me the way I was when I told Alvaro I lived on Söder.

– I’ve never seen you apologize before, he said.

Lasse and I have known each other for fifteen years. He was once my student at the Umeå Academy of Fine Arts.

– I’ve never seen you apologize before, he said.

– Don’t apologize for the circumstances you were born into, he continues.

– My circumstances were different, that’s all.

8.

The next day Lasse calls to tell me that visiting the encampments almost sent him into depression, he doesn’t know if he can handle it psychologically. He has his hands full getting on his feet, creating routines, making a life for himself in which he can function and maybe finally be healthy, finally make his own money and possibly also be an artist. He explains to me that he has what he calls a “view from the bottom”, that he “is in the darkness, in the environment, down in the dirt. Some people grow up and reach the light, reach far.”

I understand, or suspect, that he’s trying to show me something. I also understand a bit more about Katarina Taikon’s journey and that she didn’t do it on her own, but in a community in which she was active and that she helped create through her “belief in the unassailability of humankind” as Lawen Mohtadi puts it.49)Mohtadi, 122. Taikon said that “people can accuse one of just about anything” and even after 1968 when Roma where allowed to live in apartments and go to school she noticed certain attitudes. As Mohtadi puts it: “What happens when the legal obstacles to equal rights are torn down, but injustice still permeates society?”50)Mohtadi, 122.

9.

The Swedish ESF Council has been tasked with managing the Fund for European Aid to the most Deprived – FEAD. They haven’t been able to find a designation they want to use. “Swedish FEAD isn’t interested in if this is specifically about Roma or if the poor come from certain countries. The target group is simply impoverished, marginalized people who move around Europe in search of a living and a better life and who lack the right to aid and support according to Swedish law.”51)In 2015 five programs were granted more than a million kronor each for aid work for the poor in Sweden. Helen Uliczka, FEAD, “Inventering av Forskning och kunskap rörande FEADs målgrupper – resultat och reflektioner”, May 5, 2015. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.esf.se/Documents/Våra%20program/FEAD/Utlysning/Forskningsinventering%20FEADs%20målgrupper.pdf.

I emphasize that begging and giving are social actions rather than focusing on who performs them; the focus is on the activities, rather than on identities in a system. However I don’t disregard the racist attitudes inherent to the situation, they matter hugely, as they are the consequences of framing, among other things.

5.3 Giving in Free Movement Europe

1.

As previously mentioned, I hired a professional market researcher in the summer of 2011 to conduct a qualitative market survey in which givers in Sweden shared their views on those who beg and how they could become more successful at begging. The survey report states that a successful beggar:

- Is in a dire situation that is more or less temporary.

- Is active – gets something because they are doing something.

- Is relatively clean – nobody wants to be close to someone who is too dirty.

- Is “normal” – a person with “normal” clothes that one can identify with is easy to understand – and does not make the giver uncomfortable with strange or unusual rituals.

- Can offer a reason for being in said situation, or explain what the money is going to be used for.

The beggars need to meet these various requirements that we as potential givers make on them in order to appear “authentic”. Different kinds of beggars are ranked in relation to that ideal and thus the parameters listed above disqualify many of the people who beg on the streets of Sweden.

The survey also serves as the basis for a film that demonstrates how a begging person has limited room to maneuver in terms of presenting themself as credible. The giver’s worldview sets the frames for that space. So the begging person’s position is very much locked as long as there are images that imply that a.) Ultimately Swedish beggars are included in the Swedish safety net and b.) Ultimately foreign beggars – who at this point have begun to be termed migrants – are organized, either in the sense that they make obscene amounts of money, or in that they are exploited. Basically, there is no right way. It is difficult to find any agency in this situation. The dilemmas are very real. One of the givers interviewed in the market survey complained: “My resources are limited, parting with 100 kronor leaves a hole in my wallet.” So how should money be distributed when the situation is dire one way or another? What individual responsibility lies with the person who believes that fundamentally society is at fault?

2.

In the summer of 2013 I try in a similar vein to ask every person begging on Götgatan in Stockholm, from Slussen to Skanstull – a stretch I walk daily – about their image of givers on the streets of Sweden. Laura Chifiriuc is my interpreter. She subtitled my film with EU citizens begging in Gothenburg and is versed in these lines of inquiry. She’s from Romania and while we can’t assume that everybody begging on Götgatan that day speaks Romanian, it turns out everybody except for one Swedish man does. Two people don’t want to talk to us. They raise their hands when they see my camera and aren’t interested, even though Laura explains what we’re doing. The others share their stories.

We ask how business is going and what they do. They’ve come to Sweden to try to make money for their own survival and for that of their family. They tell us in various ways that life is very hard in Romania. There is no work, no support, no nothing. Some of them have had their houses destroyed by floods. When they come to Sweden they help each other with food, a place to sleep, and travel. They want to send money home but feel begging has become much harder – people give less and less and several of them think that’s due to increased economic hardship in Sweden. None of those we speak with expect the Swedish welfare state to help them in any way.

3.

In August 2013 Laura and I travel to Bucharest to interview people begging there. Despite a Romanian law prohibiting those who are deemed able to work from begging, Laura has seen people beg as recently as the winter of 2012.52)Statute 61 from 1991 prohibits a person who is able to work from asking the public for charity. Lege no. 61/1991 (Republicata 2011). Accessed April 13, 2016, politiaproximitate.ro/legea_61.html. For three days and nights we look in the types of places where you’re likely to find people begging in Sweden: In the subway, outside shopping malls, places with plenty of pedestrians. The first day we find two seniors begging to supplement their pensions. The street is also a place where they can meet people. We encounter an older man, on sick leave since 1989, whose pension doesn’t cover his rent. Around the corner we find an 80-year-old woman who tells us that her husband recently died. That the funeral was so expensive that she ran out of money. She’s there temporarily, for a week, waiting for her retirement check that has been delayed due to a public holiday. She doesn’t ask anybody for money; but people still give and many seem to know her. We move on to Calea Victoriei. On the sidewalk, across from the police headquarters a man sits begging. One of his legs has been amputated.

“For me this is the only way to survive, but I dream of a real job. I still have both my arms. I’ve heard from friends that it is possible for cripples to get upper-body work and I would love that opportunity, but nothing seems to come of it. Perhaps I should try to go to a different country.”

He says he has been begging on the street for 18 years, since the accident, and that the police leave him alone since he isn’t considered able-bodied.

Then we go to the old city, the quarters tourists visit to shop and eat at sidewalk cafes. Surely there will be beggars there. But we don’t find any. We ask some patrolling policemen and they say that some who used to beg now sell roses, safety pins and other things, the rest aren’t here anymore. Those who can’t survive in Bucharest seem to go to other European cities. Free movement within the EU has created an opportunity for people to seek sustenance in other parts of Europe. “We export beggars”, Laura’s Romanian friends joke. They don’t look happy when they say it.

The number of poor EU citizens coming to Sweden for work is expected to rise significantly. Some of them build their own homes – often together – on commons, some rent a place to sleep, some sleep on the streets. Socialstyrelsen, the Swedish national board of health and welfare, found 370 homeless EU citizens in Sweden when they attempted to map homelessness among EU citizens, however the government coordinator for the homeless, Michael Anefur, estimates that the actual number is somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 people.53)“Slutredovisning från den nationella samordnaren för utsatta EU-medborgare” [Final report from the national coordinator for vulnerable EU-citizens] presented in 2016, reads:

“In 2012 vulnerable EU citizens began to come to Sweden in larger numbers than before. Some came to beg, others to pick berries, or look for work. Over the next three years their numbers increased considerably. In the spring of 2014 an estimated 2,100 such individuals were present in Sweden. In April 2015 there were 5,000 individuals. Since then the numbers ceased to increase and a minor drop has been recorded. In November 2015 the number was estimated at 4,700 individuals. The number of children in the group varies, but is estimated at between 70 and 100.”

——Martin Valfridsson, “Framtid sökes – Slutredovisning från den nationella samordnaren för utsatta EU-medborgare”, Statens offentliga utredningar, (SOU 2016:6), 7. Accessed April 13, 2016, www.regeringen.se/contentassets/b9ca59958b5f43f681b8ec6dba5b5ca3/framtid-sokesslutredovisning-fran-den-nationella-samordnaren-for-utsatta-eu-medborgare-sou-2016_6.pdf. Aaron Israelsson, the editor in chief of Faktum magazine writes: “In 2013 alone Romania received 3.6 billion dollars from guest workers abroad. That amount includes large sums acquired through begging on the streets of Sweden, among other places. This aid is far more effective than the earmarked EU economic aid to the Roma minorities in the eastern member states. Because it turns out that the EU money has had virtually zero impact, according to the EU’s own accounting reports.54)Aaron Israelson, “Stödet till tiggaren Vanessa är unikt”, Göteborgs-Posten, March 19. 2014. Accessed April 13, 2016, gp.se/kulturnoje/1.2314378–stodet-till-tiggaren-vanessa-ar-unikt. If that is the case: then why is the “aid” given by the individual donor on the street to the person begging handled better than the official EU aid?

We didn’t find any Roma begging in Bucharest. The disabled man is not Romani, neither are the retirees, or the young man we spoke to. Nor are they migrants. There are many life stories behind begging, but the fact is that most EU citizens begging in Europe are Roma. The majority of those I’ve spoken with in Gothenburg, as well as on the streets and in the various encampments in Stockholm, have been Roma. The Roma who exploit the freedom of movement to find sustenance in other countries, when their own country doesn’t meet their needs, are trying to take control of their circumstances and improve them. The fact that Roma emigrate in higher numbers also has to do with anti-Gypsyism: the historic and continued racism directed at Roma.

In February 2012, the Council of Europe issued a report on Traveller and Roma human rights in Europe. Thomas Hammarberg ordered and published the report in his capacity as Council of Europe commissioner: “The commissioner has repeatedly highlighted that anti-Gypsyism is a crucial factor preventing the inclusion of Roma in society and that resolute action against it must therefore be central to any efforts to promote their integration.55)Commissioner for Human Rights, “Human rights of Roma and Travellers in Europe”, (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2012), 40. Accessed April 13, 2016, www.coe.int/t/commissioner/source/prems/prems79611_GBR_CouvHumanRightsOfRoma_WEB.pdf.

On 20 March 2014, Hammarberg makes a statement on Sweden’s treatment of Roma EU migrants. “The municipalities are unwilling to do anything to indicate that they understand the situation, they won’t even install a toilet. Nor do they want to create more beds in homeless shelters. Nothing is done to improve daily life.”56)Daniel Vergara, “Hammarberg: ‘Sverige hycklar om romska migranter’”, Expo, March 20, 2013, expo.se/2014/hammarberg-sverige-hycklar-om-romska-migranter_6445.html. Responsibility is shunted upward and sideways when the Romanian ambassador proposes that Sweden needs to ban begging, as Romania would then care for its own. At the same time one points to the overly national EU policy and argues that the individual nation-state – in this case Romania – is responsible for using the EU aid it is given for Roma. They need to “pay their dues”, as some from the Swedish liberal party put it. “The government exploits EU cooperation to circumvent accusations that they are creating policy in nationalistic self interest.”57)Peo Hansen, EU:s migrationspolitik under 50 år: ett integrerat perspektiv på en motsägelsefull utveckling, (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2008), 218. The alternative appears to be further centralization of power.

On March 25, 2015 the Swedish government presents its white paper on abuse and violations of Roma in the 20th century. The same day that the report is issued, Socialstyrelsen issues a press release in which they accept historic responsibility: “Socialstyrelsen and medicinalstyrelsen [the national board for medicine] have repeatedly been more than passive executors, they have been active in discriminating against Roma and Travellers, or limiting their access to social support, says Eva Wallin.”58)Socialstyrelsen, “Allvarliga övergrepp mot romer och resande i Socialstyrelsens historia”, March 25, 2014. Accessed April 13, 2016, http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/nyheter/2014mars/allvarligaovergreppmotromerochresandeisocialstyrelsenshistoria. Does this include present-day Romani EU citizens? ☞

Again: The discourse on begging is associated with, but should not be conflated with, the Roma situation. The Schengen Agreement (Romania is not yet a member of Schengen, but is expected to become one according to the Swedish government’s informational homepage about the EU) was updated in June 2013 in regards to interactions between member states.59)EU-upplysningen, “Schengen och fri rörlighet för personer”, last updated May 3, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2016, http://eu-upplysningen.se/Om-EU/Vad-EU-gor/Schengen-och-fri-rorlighet-for-personer/. “The new rules for evaluation mean a transition from the current inter-state system for audit to an EU strategy in which the central coordinated role is given to the Commission.”60)“The new evaluation rules mean a shift from the current intergovernmental system of peer review to an EU-based approach where the central coordinating role is given to the Commission.” European Commission, Memo: “New Schengen Rules to Better Protect Citizens’ Free Movement”, 12 June 2013. Accessed April 13, 2016, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-536_en.htm. What does this mean? To what extent can a country interfere with another country’s actions when this has consequences for other member states, for instance regarding reactions to begging? In which way are the Romanian and Swedish systems connected (if at all) because of the EU? Hans Swärd, Professor of Social Work at Lund University, answers my questions: “They are connected for certain groups within the labor market or the educational systems. There are rules regarding the right to study in other EU countries and, if you work in another EU country, there are a number of agreements. The problem is that the system does not include those outside the labor market.”61)In the summer of 2014 a survey was commissioned: “Utredningen om trygghetssystemen och internationell rörlighet”, [Survey of safety systems and international movement] which aims to create an overview of Swedish social insurance from an international perspective. Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish government surveys]. The survey is to be presented by January 31, 2017.

——Socialdepartementet, “Tilläggsdirektiv till ToR-utredningen. Utredningen om trygghetssystemen och internationell rörlighet”, (S 2014:17), Regeringskansliet, December 10, 2015. Accessed April 13, 2016, www.regeringen.se/rattsdokument/kommittedirektiv/2015/12/dir.-2015133/.

The question of the situation of poor EU citizens has reached a point where it has begun to generate resistance from other parts of society. During a few winter months in 2013 and 2014, a group of activists at the Cyklopen cultural center in Högdalen in Stockholm demonstrate through action that they see and hear the predicament of the people who beg. They organize clothing drives and actions. The organizer is invited to sit on the couch at Gomorron Sverige, a morning news show on national Swedish TV.

“Why are you doing this?” the host asks Anna Silver, who started the Facebook group and organized the drives. “It could have been me”, she says.62)After the authorities tore down the encampment in Högdalen on March 13, 2013 the EU-migrants made their way to Sollentuna to build a new encampment. With that the discussion about solidarity across national borders is underway. She doesn’t speak for them. She doesn’t claim to give them a voice. She sees them and she sees herself in them, sees all of us, enmeshed in various cultural and social structures and conditions.

“The mechanical solidarity that has its roots in highly homogenous societies, presupposes sameness between people; similarity creates cohesion. Organic solidarity, a more solid unit, conversely, is built on difference”, writes Sven-Eric Liedman, professor of history of ideas.63)Sven-Eric Liedman, Att se sig själv i andra, om solidaritet, (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 2012), 27.

The registry that the police has been criticized for – there is an ongoing investigation into whether it was an ethnic registry of Roma or not – has, by dint of the subsequent debates contributed to making visible the image of Roma held by an institution of power serving national justice. Protests are staged by groups such as Cyklopen, Aktion Kåkstad, Allt åt Alla, Det Kunde Varit Jag, Ingen Människa är Illegal, Insamling för Hemlösa EU Migranter i Högdalen, Linje 19, Solidaritet för 17, Vänsterpartiet Sollentuna and others. On 13 March 2014 job-seeking and homeless EU citizens were ousted from their encampment in an abandoned military area in Helenelund, in Sollentuna. Later the encampment was demolished by bulldozers.64)See my documentation in the archives. When the authorities enforce statutes and rules there is always room for interpretation. In its report, Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare] calls for more knowledge on what the praxis is for these migrants, for the social services in the various municipalities and for the volunteer organizations. “Many don’t know the rules. […] One wishes that everyone would see the possibilities rather than the restrictions in the statutes.”65)Socialstyrelsen, “Hemlöshet bland utrikesfödda personer utan permanent uppehållstillstånd i Sverige”, (May 2013), 34. Accessed April 27, www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2013/2013-5-3.