1.1 The First Encounter

1.

It is late 2010. For some months now I’ve passed a number of people during my daily rounds, they’re kneeling or walking jerkily holding plastic cups. They ask for money and speak languages I don’t understand. Something new is happening on the city streets.

One day I see a man who is standing, shaking, he’s leaning on a cane and holding out a cup with his other hand. For a while I stand at a distance, looking at him. The situation is complex and confusing, I become emotional. When I approach him to speak to him, my body language doesn’t project friendliness and mutuality – reasonable conditions for a dialogue – and I know all this in that moment, it is my job to know it. I also realize that I am about to take leave of several of my founding ethical principles, the stance that I have worked toward during my twenty years of artistic practice, but right now I am ruled by adrenaline, my heart is pounding. I step up to the man, iPhone in hand, and film him, while I ask in Swedish if he needs help. He doesn’t understand. I then ask again in English, then in Spanish. No, he needs money, he tells me in Italian. He extends a large cross that he is wearing on a chain around his neck. This doesn’t compute for me; what does the cross have to do with his situation, why is he begging, can’t he go to social services? I ask why he isn’t working, if he is sick, if he needs care. “Do you want me to take you to a hospital?”, I insist, but he doesn’t understand and says that he has several children that need food. He says he came by bus from Romania. You came by bus, oh, so you’re a tourist? I say. He looks at me uncomprehendingly and the conversation is over. “Please, no television,” he says. No, I won’t show this, I tell him, and mean it, trembling.

What happened here? I’m ashamed of my actions and of not being able to control my reactions in relation to a larger picture, in relation to some kind of social and political matrix.1)Sara Ahmed, professor of race and cultural studies, describes how shame can be experienced in a variety of ways: “Shame can also be experienced as the affective cost of not following the scripts of normative existence.”

——Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, second edition, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 107.

2.

Later, as I watch the video snippet, I want to destroy it, erase it, erase my embarrassing incompetence, but I stubbornly hold on to it as a document of how my own reaction – my unconscious bodily action – ruled me in relation to that man. There is an authenticity in these images that I can’t recreate, in how I encounter, how I see, how I relate to his space.2)Philosopher Luce Irigaray describes the necessity of air space in an encounter as follows: “Air that which brings us together and separates us. Which unites us and leaves a space for us between us. In which we love each other but which also belongs to the earth. Which at times we share in a few inspired words. Air, which gives us forms from within and from without and in which I can give you forms if the words I address to you are truly destined for you and are still the oeuvre of my flesh.” Luce Irigaray, I Love to You: Sketch for a Felicity Within History, (London: Routledge, 1996), 148. He became instrumental to my image and I became partially blind. What didn’t I see and what did I see. And what did I see when I didn’t see?

A memory: I am little and want to grab the hair that is hanging in front of me, it’s tempting because there is so much of it. But I can’t grab it precisely because there is so much of it. And when I pull the hair it has consequences, my desire is the other’s pain.

My action reveals me to myself and to my surroundings. If I want to see you I also need to see myself and it seems the unconscious in that action can teach me to see. I didn’t think for myself, I let preconceived notions override my agency. Now, at least, I have the opportunity to reflect on my failure, without failure, no ethics, as Simone de Beauvoir once said. If I were to neglect reflecting over what just happened I would be submitting to what the Norwegian philosopher Jakob Meloe describes as the dead gaze, which doesn’t see and doesn’t comprehend.3)This account of philosopher Jakob Meloe’s theory is borrowed from a lecture by Professor Ingela Josefsson in a postgraduate course in epistemology at STDH, Stockholm University, September 21, 2011–February 6, 2012. I’ve often noticed that those who pass the people who beg appear to ignore them completely. The person who begs makes a request, addresses the passer-by, but gets no answer. How often is this type of seemingly selective perception rooted in a conscious decision? In the encounter that I describe as my first I felt a dissatisfaction pertaining to what Meloe calls the ignorant gaze; when someone sees and doesn’t understand and also understands that she doesn’t understand. Among other things it was this limit of understanding that I wanted to approach when I walked up to the man, but first I must, without knowing how, try to tap into my ignorance, challenge a boundary. I want to arrive at what Meloe terms the knowing gaze, which sees and understands that the experience is a learning process. In addition I have the option of using my knowledge as a visual artist to explore what other images might be created. For me it isn’t enough to depict an experience. I also want to transform an event into an experience, that way I might stand a chance of seeing old insights in a new light, maybe even nudge the boundaries of language somewhat. In one of her graduate seminars Ingela Josefsson, professor of Working Life studies, claims that experiences without reflection are just events without meaning.4)Ingela Josefsson, doctor of Scandinavian languages, was the vice-chancellor of Södertörn University until June 2010 and is Professor of Working Life studies at the Center for Studies in Practical Knowledge at Södertörn University. Among other things she maintains the importance of tacit knowledge or practical knowledge and says in an interview that she noticed that: “A gap has formed between what one could call academic praxis and the praxis in practice.” Practice-based knowledge is a term developed in the Anglo-Saxon world for praxis-based research but Ingela Josefsson and others choose the Swedish term praktisk kunskap, which they translate as practical knowledge in English (rather than the term tacit knowledge which was used initially). It aims to be professional or working life knowledge. Though the terms may seem synonymous, these are separate discourses. Markus Prest, “Teorin måste utformas på praktikens villkor”, Ikaros 3.10 (2010). Accessed May 9, 2016, www.fbf.fi/ikaros/arkiv/2010-3/310_prest2.pdf.

——During the same Ph.D. seminar Josefsson refers to Norwegian philosopher Hans Skjervheim who writes: “Engagement is a foundation of human existence, it has to do with what Heidegger calls Geworfenheit (thrown-ness). What we can choose is what we want to engage in, or we can let others choose for us.” Hans Skjervheim, Ian Hamilton, and Lillemor Lagerlöf, Deltagare och åskådare. Sex bidrag till debatten om människans frihet i det moderna samhället, (Stockholm: Prisma/Verdandi, 1971), 21. This is the dilemma in which I decide to engage my gaze. A few weeks later I begin a creative project titled: How Do You Become a Successful Beggar in Sweden? I want to explore the choreographies of begging and giving and will continue do so until 2016.

1.2 Notes on the Text

Along with six staged works this text constitutes my thesis.5)All works are shown together in a travelling exhibition: At Skövde Konsthall, Varbergs Konsthall, and Skellefteå Konsthall 2015–17. There have also been a number of exhibitions and street screenings of individual staged works. In connection with the dissertation there will be an opportunity to see the works at Skellefteå Konsthall, starting October 30, 2016, which is one of several exhibition windows for the material in the thesis. My artistic work is physical, spatial, and temporal, and these parameters also affect the presentation. The thesis includes and discusses all these forms of art and presentation. This presentation uses the same approach as the staged works shown in art spaces, at street screenings, or as photo manifestations on social media, it was developed with the intention that text and other renditions of this work should be regarded as a whole.

My first encounter – or rather non-encounter – with a person who was begging prompted me to embark on a five-year exploration of what happens between the begging and the giving on the streets of Sweden; I pose questions about the images at play in the social choreography of begging and giving – how can images be activated in this context and new ones generated? I explore begging and giving in the urban landscape, in the media, and in other activities that stem from these actions. I use images as my starting point; images of action and images that implicate, images that are set in motion, images that generate motion (moving images) and the reverse: new movements generate new images. For each work, I’ve described the concrete work process and what the negotiations with those involved have been. The text fragments that appear here and there are my “internal negotiations” and of importance to the work.

I discuss the practice of other artists in a number of reflective and analytic texts.6)All fall under the umbrella term participatory art. They are: A documentary participatory-performative film, Enjoy Poverty by Renzo Martens, a documentary participatory-performative film installation, Kropp – Erfarenhet – Kunskap [Body-Experience-Knowledge] by Ioana Cojocariu, a public space-performance, Persondesign, by artistic duo Bogdan Szyber & Carina Reich, a participatory-public-installation, Lights in the City by Alfredo Jaar, and a site-specific action painting and cutting by AKAY & KlisterPeter. I use these terms to show how contemporary art uses and compiles various practices and methodologies. These artists work both within and outside of art as an institution. Their – and my – work has in common that it is dependent on the people involved in the social situation discussed in its staging. A form of participatory performance is involved in the production process one way or another – and aims to generate images to be presented to an audience.7)Performance is an art form that can be part of works in various ways. Stimulated by my colleagues I investigate possibilities in practice, and have done so since the early 1990s. My background was in painting during the 1980s. I was active in video art in the 1990s, in the tradition that involves a performance in front of the camera in a closed room, alone or with a participant, which is then screened as an art installation. My practice later transitioned to participatory performative staged works and action documentary (www.ceciliaparsberg.com). Since the turn of the millennium I’ve worked with participation in different forms, some of these can be designated variations of delegated performances, which is a term used by Claire Bishop. But these also differ from each other, see further discussion in the text. This thesis work contains the staged works What Images does the Giving face? & What Images does the Begging face?, chapter 2, Body on Street, chapter 4, and The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving, chapter 7, where performance forms a foundation for my work. In these participatory performances I am the employer, I pay all participants and everybody knows that this will become a film for an art installation. I am describing art movements and –isms so that we know that we mean the same thing while talking, but it is not within the scope of my thesis to analyze them. Much like the term “art” I use “performance” as an open term.

——The meaning of performance in relation to performative acts is analyzed by, among others, artist and art theorist Barbara Bolt, she refers to philosopher of language John Langshaw Austin, Judith Butler, Jacques Derrida and others.

——Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?” PARSE 3, (2016). An older and shorter version can be found online: “A Performative Paradigm for the Creative Arts?” accessed May 9, 2016, www.herts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12417/WPIAAD_vol5_bolt.pdf. “Performance implicates the real through the presence of living bodies”,8)Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The politics of performance, (London: Routledge, 1993), 148. as performance theorist Peggy Phelan puts it. She adds: “Performance clogs the smooth machinery of reproductive representation necessary to the circulation of capital.”9)Ibid., 148.

Phelan positions the constative (self-referential acts of speech – findings) in contradiction to the metonymic: “Metonymy is additive and associative; it works to secure a horizontal axis of contiguity and displacement.” (Ibid., 215). She also maintains that the performative displays independence from an external reference in present actions. In her text Phelan uses photographer Cindy Sherman’s self-portrait as an example of performance. Cindy Sherman’s photographs describe a female body – her own – but she doesn’t reproduce the reference. She is an actor who executes a performance in front of the camera (in different ways and with various “additions”)10)“Just as her body remains unseen as ‘in itself it really is,’ so too does the sign fail to reproduce the referent.” (Ibid., 150). . The performance she has staged for the production of the photograph is unique, it hasn’t been documented, rather it generates a new image. Sherman’s photographs destabilize the relationship between the symbol, the representation, and the female body and thus the reproductive representation. Her photographs participate in – but also clog – the smooth machinery necessary to the circulation of capital.11)In another example Phelan discusses the works of Sophie Calle, an artist who works with stories and who “is increasingly moving toward performance”, here on a work at the Isabella Gardner Stewart Museum in Boston: “The descriptions fill in, and thus supplement (add to, defer, and displace) the stolen paintings […] the interaction between the art object and the spectator is, essentially, performative – and therefore resistant to the claims of validity and accuracy endemic to the discourse of reproduction. […] The description itself does not reproduce the object, it rather helps to restage and restate […].” (Ibid., 147).

——According to my interpretation Phelan is talking about how the absence of objects together with the stories of the vanished objects create images in the viewer, a performative act takes place between art object and viewer that generates new images. The way I read Phelan what she means by reproduction is to reproduce an image that I have of somebody else or something else, that is when I reproduce the image I have of you – it is a kind of objectification. But performance demands that these images be reformulated and doing so necessitates a sensual physicality. It’s often difficult to discern reproduction from representation, it is exactly this balancing act that takes place in cooperation with the participants: to no longer reproduce an image I have of you, but to try to reformulate – and arrive at a new image. I describe it as the performative process, activating images and generating new ones. There is no general method for how to go about this. Every work that I have produced over the course of this thesis has its own process, and taken together these variations can be seen as a method (guided by the research questions) within the framework that the study of the subject constitutes.

The works of all artists in the thesis are ethically challenging and aim to reveal and activate various social gaps as spaces for political action; some of these can – in terms of their staging – be termed delegated performances to use the terminology of art historian Claire Bishop.12)In the mid-1990s a particular kind of performance emerged, described here by Claire Bishop: “Although this trend takes a number of forms, […] all of this work […] maintains a comfortable relationship to the gallery, taking it either as the frame for a performance or as a space of exhibition for the photographic and video artefact that results from this. I will refer to this tendency as ‘delegated performance’: the act of hiring non-professionals or specialists in other fields to undertake the job of being present and performing at a particular time and a particular place on behalf of the artist, and following his/her instructions.” Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, (New York: Verso, 2012), 222.

——One example is the work of Santiago Sierra, in which he hires workers to complete simple tasks in the exhibition space during the time of the exhibition, such as hold up a wall that’s about to fall, or part of a wall. His performance alludes to the socio-economic system. “Although the artist delegates power to the performer (entrusting them with agency while also affirming hierarchy), delegation is not just a one-way, downward gesture. In turn, the performers also delegate something to the artist: a guarantee of authenticity, through their proximity to everyday social reality, conventionally denied to the artist who deals merely in representations.” (Bishop, 237). Bishop addresses a number of variations on delegated performance and discusses these in chapter 8.

——The works by Ioana Cojocariu and Szyber & Reich that I mentioned can be termed ‘delegated performances’ according to Bishop’s definition, as can my works What Images does the Giving face? & What Images does the Begging face? and The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving.

——The ways in which the performance of the 1990s differs from that of the 1960s and ’70s is also interesting in this context, and as Claire Bishop puts it: “Artists in the 1970s used their own bodies as the medium and material of the work, often with a corresponding emphasis on physical and psychological transgression. Today’s delegated performance still places a high value upon immediacy, but if it has any transgressive character, this tends to derive from the perception that artists are exhibiting and exploiting other subjects.” (Bishop, 223). The examples of staged works that are addressed in the thesis also exist within and aim to discuss this kind of drawing of ethical and aesthetic boundaries. But this term alone is not enough to encompass the methodological intent that I claim characterizes my work and that of the previously mentioned artists. The philosopher Boris Groys maintains that this is a new phenomenon in comparison to other movements in history and names this type of art by naming the intention of the actors: “Art activists react to the increasing collapse of the modern social state […] Art activists do want to be useful, to change the world, to make the world a better place – but at the same time, they do not want to cease being artists.”13)Relational Art is a tendency in contemporary art that art critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud highlights with his book Relational Aesthetics, (Dijon: Les Presses Du Reel, 1998), and that has influenced my artistic practice, But with my engagement in social and policy issues my practice is closer to what Boris Groys describes: “The phenomenon of art activism is central to our time because it is a new phenomenon – quite different from the phenomenon of critical art that became familiar to us during recent decades. Art activists do not want to merely criticize the art system or the general political and social conditions under which this system functions. Rather, they want to change these conditions by means of art – not so much inside the art system but outside it, in reality itself.”

Boris Groys, “On Art Activism”, E-flux journal, 56, (2014): 1. Accessed April 30, 2016, www.e-flux.com/journal/on-art-activism. They are forged in the relationship between the ethical, the aesthetic, and the political. Thus they create points of contact with theoretical fields relevant to the work such as political philosophy, sociology, cultural geography, the history of ideas, and anthropology.

There are two whole chapters on the image. The ideas that have become important in the artistic practice are the same as those that guided the theoretical framework. When I examine an image in practice it’s about the relationship between viewing and participating – about which position I inhabit in the creative process and the relationship between imagining and producing an image. Which is to say that I don’t examine image as production medium (in this thesis). Rather, I use specific designations when describing specific techniques, for instance photo, film, painting, film installation. I use the word “image”, both in the sense of imagining something without physically standing in front of it, that is an image that belongs to the thought and thinking; as well as in the sense that images are actions, that what one sees is experienced as a response and perhaps also as a responsibility – something that needs to be revealed and transmitted to a viewer. Philosopher Hannah Arendt’s book The Human Condition has guided me in understanding how actions and thoughts occur as two-way communication; thought demands action and concrete experiences demand the abstraction that thought can supply.

In chapters 3 and 8 – Places I and Places II – I have photographed places (or non-places) that those who beg have set up on the street. Together they transmit images of a gap between representation and presence.

In chapter 4 I explore gestures in collaboration with different people in different cities; their images are made physical and become performative in the photo demonstration Body on Street. The participants’ individual experiences – images that they have – of the situation of giving in relation to begging are our points of departure. We explore the boundaries between the personal and social experience and also what capacity (influence) these images can have as physical movement on patterns of movement in the urban landscape. When Barbara Bolt claims that “The performative act doesn’t describe something but rather it does something in the world,”14)Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?”. she is saying that a performative act is about power and effect that can affect both the participant and the audience.15)“The essay argues that the performative needs to be understood in terms of the performative force of art, that is, its capacity to effect ‘movement’ in thought, word and deed in the individual and social sensorium.” (Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?”, 134.) In the urban space, in front of onlookers passing by, still and relational acts are improvised, new images are generated – photographs that frame the movements in the urban environment in which they are enacted are passed on as a photo demonstration on social media and in exhibitions to the audience. This procedure could also be seen as reverse street photography.16)“The street photographer can be seen as an extension of the flaneur an observer of the streets (who was often a writer or artist)”. Susan Sontag, On Photography, (London: Penguin, 2008), 55.

——Street photography is “conducted for art or enquiry that features unmediated chance encounters and random incidents within public places. […] Street photography can focus on people and their behavior in public.” “Street Photography”, Wikipedia. Accessed May 14, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Street_photography. The work is the entire chain of events.17)A workshop has been arranged for each exhibition together with participants from that town, the photos that are generated are then displayed in the exhibition space together with the others from the series Body on Street. ☞

Since my studies for the most part have been clearly situated in time and space and developed in relation to the public debate, my investigations have also demanded a public space. Over the course of the project I’ve kept a project blog – tiggerisomyrke.se [beggingasaprofession.eu] – this has led to my being contacted by and participating in radio shows, newspapers, and magazines. For every exhibition there has been a panel with a local politician and representatives of a local aid organization. In this way I’ve let the debate on begging and giving in Sweden influence my investigation and I, in turn, have influenced the debate. I discuss this in further detail in chapter 5. But the dissertation isn’t just about explaining a course of events, rather I mention this to emphasize that I have worked within a certain time period and within a certain framework. Judith Butler’s discussions of framing have been important in terms of trying to make this frame visible to some extent. Sara Ahmed is one of those who researches the meaning of emotion in the space between people and her texts have been crucial to gaining a closer understanding of the drama that is triggered on the street between those who beg and those who give, the public debate, as well as the ways in which politicians have reacted to the phenomenon. She also writes about methods for perceiving inter-human space, especially in situations in which there is a palpable inequity or hierarchy.

Chapter 6 deals with the drawing of boundaries that are noticeable in various ways; social points of contact are sensual, that is where the political is founded: In people’s affectivities and reactions. And if a physical wall is manifested as an aesthetics of loss – and experienced as an abyss – then where can the knowledge be found? How can one think around, past, over, under the wall about what learning is? Throughout I use philosopher Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback’s thought “In order to develop a phenomenology of appearance it becomes necessary to investigate what visibility means, and thus critically challenge the difference between words and images as a difference between knowledge representation and knowledge production through images.”18)Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback, Att tänka i skisser, (Gothenburg: Glänta, 2011), 12. But I won’t try to account for the difference between pictorial notions and conceptual knowledge. This relationship has a problematic history that lies outside my field of inquiry.19)Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback explains this relationship in Att tänka i skisser. She writes: “The longstanding philosophical dispute between logos and mytos, reason and myth, is primarily a struggle between idea and image, between abstraction and fiction, and thus between two types of distancing from the real.” (Ibid., 7). Nor am I bound to this line of thinking. At times I also find inspiration in a method that is similar to that of musician Eva Dahlgren: “I’ve always written songs in images.”20)Anna Bodin, “Jag vill översätta det fantastiska ljuset till musik”, April 17, 2016, Dagens Nyheter. Accessed April 26, 2016, www.dn.se/arkiv/dn-kultur/jag-vill-oversatta-det-fantastiska-ljuset-till-musik. She means that she writes text in images, and continues, “I had an image in my head of something that was straight and crispy, the colors were kind of cold and all of that.” That becomes text, set to music, that she later sings at her shows.

Chapters 7.1 and 7.2 consist of The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving. The Chorus of Begging is made up of people who beg on the streets and The Chorus of Giving is made up of people who give to people begging on the streets. The installation with the improvised singing by the filmed choirs is shown to viewers who stand between the projections of the choirs – in the manner they were filmed. The production of this artistic work can be described in the words of Claire Bishop: “A third strand of delegated performance comprises situations constructed for video and film. […] Recorded images are crucial here since this type frequently captures situations that are too difficult or sensitive to be repeated.”21)“[…] key examples might include Gillian Wearing, Artur Żmijewski and Phil Collins.” (Bishop, 226). For three days the 24 members of the choirs were put through a specific form of choral training in order to improvise song without words or music. In Bishop’s words they are “[…] works where the artist devises the entire situation being filmed, and where the participants are asked to perform themselves.”22)“What I am calling delegated performance in all its contemporary iterations (from live installation to constructed situations) brings clear pressures to bear on the conventions of body art as they have been handed down to us from the 1960s.” (Ibid., 226).

Chapter 7.1 is about preparations, process, treatment of images, and a first presentation consisting of an outdoor installation in a shipping container. To me it felt important to convey the images that had been negotiated, experienced, and renegotiated in a closed room for three days. This is why we made a process film: On the Production of The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving.23)“On the Production of The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving”. This film is shown in conjunction with the installation. I also screen it when I give talks in educational, as well as social, and political contexts.24)As a keynote speaker in connection with FEAD’s announcement of 50 million kronor in grants that the organizations of civil society could apply for, I talked about how we developed the choral arrangement and showed the same split-screen presentation that is shown in the thesis.

——“The overall goal for FEAD is that people who are in a socially vulnerable position will gain increased social participation and autonomy. More specifically this is mainly about EU and EEA citizens who stay in Sweden for shorter periods of time.”

——“Nationell utlysning: Fead-insatser 2015–2018”. Accessed May 14, 2016, www.esf.se/Documents/Våra%20program/FEAD/Utlysning/Utlysning%20Fead%202015.pdf.

——Among other lectures and writing assignments I was also asked to publish an article, mainly about the process of staging the choral arrangement, in Socialmedicinsk Tidskrift, “Den nya utsattheten – om EU-migranter och tiggeri”, Vol. 92, No. 3 (2015). Accessed May 14, 2016, http://socialmedicinsktidskrift.se/index.php/smt/issue/view/105. With the help of this film I can give an account of our unique collaboration and experimental method, so far it’s been screened at five solo exhibitions in Sweden during a time at which the discussions about begging and giving have been intense.

In chapter 7.2 I discuss symmetry and asymmetry in the The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving using the works of Butler and Lévinas.

The viewer (as well as the reader) of this thesis misses out on the effect of the sensual experience of physically standing between the projected choruses at a scale of one to one, in the installation.25)“Contemporary performance art does not necessarily privilege the live moment or the artist’s own body, but instead engages in numerous strategies of mediation that include delegation and repetition; at the same time, it continues to have an investment in immediacy via the presentation of authentic non-professional performers who represent specific social groups.” (Bishop, 226). Instead the thesis depicts a split-screen that I also use to project the work on the walls of buildings and trucks at night, in the urban landscape, as a street screening with audio. This version relays a somewhat different effect, which I write about. This is also the version that I screen when I lecture in the contexts mentioned above.

I have expectations on the viewer. I want to be able to hand over the images my participants and I have arrived at through improvisation to a viewer and at the same time establish a trust-based relationship with the viewer as recipient.26)All participants know from the start that photographs and films will be shown in exhibitions and eventually in the media.

In total a couple of hundred begging and giving people have participated in my presentations, one of the key concepts in this context is co-presence. I’ve borrowed this term from cultural geographer Sara Westin who uses it in her doctoral thesis to discuss the movement of people in an urban space. She asserts the importance of urban planning taking into account how urban spaces are populated – the ways in which people’s movements define the space. This mindset has complemented the others I’ve mentioned and has been important to my work with Places I, Places II, and in particular with Places III where the dissertation alights. The latter describes a place in transformation where some people are included in the social structure and others are shut out for various reasons, but continue to live just outside. This is also where my thesis drills down and makes visible a self-organized cluster of artists whose work seems to resist the reproductive capital by giving in a way that doesn’t seem to require anything in return, doesn’t accumulate, just gives. That kind of giving is different than helping. The dissertation ends with the opening of an investigation in A Place in Europe, where the research questions can be put into play in new ways.

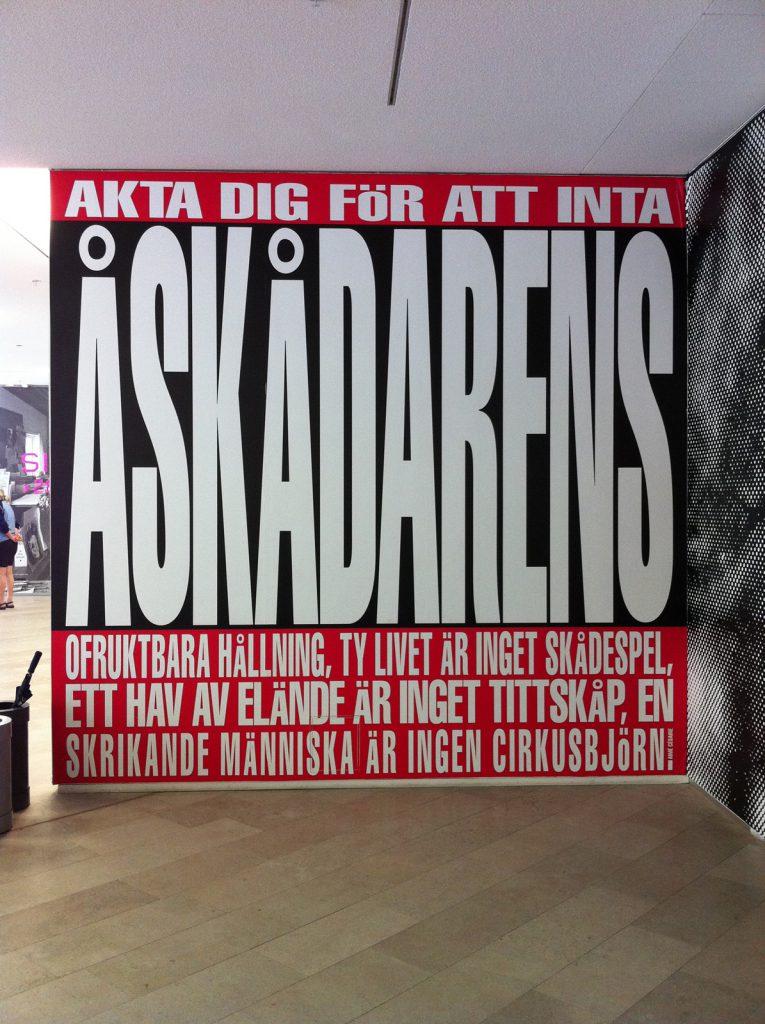

Life is no spectacle, a sea of misery no diorama, a crying person no circus bear!”

Photographed at the Modern Museum, Stockholm, 2011. The quote is by Aimé Cesaire.27)Aimé Cesaire, 1913–2008, was an author, poet, playwright, and politician from Martinique. He founded the expression Négritude in the journal L’Étudiant Noir in 1935 and was active in the Négritude movement, an ideological-literary movement that arose in Paris. The movement was anti-colonial and aimed to replace the white man’s disdain for Black people with a revaluation of Black culture and instill pride in Black people about their origins and color. The Négritude movement was a reaction against French politics of assimilation. The goal was to articulate a culture of one’s own. Léopold Senghor was the most influential ideologue of the first years of the movement. The Négritude movement was introduced to a broader swath of the white public by Jean-Paul Sartre in his foreword to Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache de langue franςaise, in 1948.

1.3 Designations, Images

The title of this thesis is How Do You Become a Successful Beggar in Sweden? With it I aim to critically review and challenge a linguistic context, as well as actual phenomena. The title serves as a starting point for discussions and as sort of a verbal engine. The question of how one can succeed is posed by a person in a state of emergency, begging. Or by a person who is expected to be, or is, a potential giver to the person who is begging – how can success be achieved? A gap opens up between those who pose these questions, language doesn’t hold. Does this mean that something new might emerge? Is it possible to make one’s way outside of the frame of knowledge, outside the hierarchy of power that also controls facts? Perhaps. In any case this is the way in which I attempt to find a point of entry into the questions that are being discussed in the media and on various political levels parallel to this. It is my intention to show how ruptures, openings, gaps, voids, spaces in which language loses contact with meaning and content, can be conveyed, visualized, embodied, and fashioned. Art is one way of doing this.

When I began my project in 2011 the media used the single designation “beggars” for people who beg on the streets. Initially I chose to embrace this problem of definition and regard beggar as an open concept.28)“The distinction between open and closed terms was important in this context. A closed term is a term that can be defined by the traditional ‘if and only if’ definition, that is by giving the necessary and sufficient conditions for something falling under this term. Examples of these types of definitions are mathematical terms as two, three, four, circle, equilateral triangle, and so on. An open term is a term that can’t be satisfactorily defined in this manner.” Tore Nordenstam, Exemplets makt, (Dialoger, 2005), 31. To solidify a definition would be to risk alienating, rather than problematizing an effect of poverty, or otherness, that stems from social inequality. I reasoned that if the definitions of beggar and begging respectively remain open, there is no particular group of people to be defined and named. My hope was that a necessary discussion about what begging is would subsequently arise.29)In order to understand ‘open terms’ one needs to know series of cases that fit the pattern, according to philosopher Tore Nordenstam. “These are necessary conditions for the possibility of understanding and action.” (Ibid., 59).

——“Art” is an example of an open term, it’s only characterized through the shifting examples that are contained in it. The strength in art is that it shows the weaknesses in the definition process.

——Begging is an open term. Can begging be categorized as an occupation – what counts as begging? Is peddling begging? Is recycling cans begging? How many hours a day does one need to work to count as a beggar? Are buskers beggars? “The law on busking says: According to the municipal assembly circular 1995:41 collecting money in connection to performing street music doesn’t necessitate a permit, partly due to the fact that this would limit the individual’s freedom to perform a musical or other artistic work, partly due to a musician’s collection in an instrument case, or on an article of clothing being a passive act. It is a different thing if the musician is walking around in the audience collecting money. This act is to be seen as collection of money and can necessitate a permit in accordance with local regulations (prop. 1992/93:210 s. 141 f). Exceptions to the need for permits can be made in cases such as school classes collecting money to aid organizations.” Ann Sofi Agnevik and Emilia Danielsson, “Några juridiska frågor gällande utsatta EU-medborgare”, September 12, 2014, Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting, 9. Accessed April 26, 2016, www.skl.se/download/18.2371797b14a4dca6483fe13/1418804156789/SKL-juridiska-fragor-om-utsatta-EU-medborgare-2014-12-09.pdf.

“Success” is a very mediagenic word. The desire to be successful could apply to every line of work, but when I pose the question in relation to someone who has to beg language seems to crack. A disabled man in Bucharest who apparently (begging is forbidden in Romania) is permitted to beg, since he is sitting across the street from police headquarters when we interview him, says to me, “If you can accept that you won’t get more than the minimum needed to survive, then it’s successful. It depends on what your limits are. For me, if I can survive, then it’s successful.”30)An interview that was filmed by me with interpreter Laura Chifiriuc in Bucharest, August 2013. Those who beg are at the bottom of the social hierarchy, they are the poorest, and often do not have birth certificates or passports and thus aren’t part of any formal community. The image of success – an improved future situation – is transmitted by the prevailing system, which has created free movement. By having the question about success remain, I hope that the dissertation will also convey the shifts in terminology over the five years that my research has been conducted.

Over the years a number of designations have been used by Swedish media for people who beg: The beggars, the people who beg, EU-migrants, Roma who beg, the Roma from Romania, the Romani EU-migrants, the EU-mobile, the vulnerable EEA-citizens, The EU-citizens who have the least resources and thus beg.31)In his investigation on vulnerable EEA citizens in Sweden, national coordinator Martin Valfridsson has described as “vulnerable” those who don’t have the right to access Swedish welfare. The report became official in January 2016. The image of which people are included in this term is complicated by the following description in the introduction to his report: “By vulnerable EU citizens this report means individuals who are citizens of another EU nation and who do not have so-called right of residency in Sweden. Those who don’t have right of residency have significantly lower chances of accessing welfare here. In order to obtain a right of residency, it is in somewhat simplified terms, necessary to have a job or good chances of obtaining a job.” The report gives a very short history of begging in Sweden and especially points to the last three years that in the introduction are described as follows: “In 2012 vulnerable EU citizens began to come to Sweden in larger numbers than before. Some came to beg, others to pick berries, or look for work. Over the next three years their numbers increased considerably. In the spring of 2014 an estimated 2,100 such individuals were present in Sweden. In April 2015 there were 5,000 individuals. Since then the numbers ceased to increase and a minor drop has been recorded. In November 2015 the number was estimated at 4,700 individuals. The number of children in the group varies, but is estimated at between 70 and 100. Martin Valfridsson, “Framtid sökes – Slutredovisning från den nationella samordnaren för utsatta EU-medborgare”, Statens offentliga utredningar, (SOU 2016:6), 7. Accessed April 12, 2016, www.regeringen.se/contentassets/b9ca59958b5f43f681b8ec6dba5b5ca3/framtid-sokesslutredovisning-fran-den-nationella-samordnaren-for-utsatta-eu-medborgare-sou-2016_6.pdf.

When terms such as EU-migrants or poor EU-migrants are used, begging is connected to migration and migrants. “To describe someone as an EU-citizen, rather than as a migrant, or migrant worker, signals that the person in question has rights that the state is bound to honor, while migrants have the rights that the state chooses to give them.” So writes political scientist Meriam Chatty. She claims that the term “migrant” isn’t neutral, rather it is normatively charged with a content relating to safety. “While the citizen is the person who is protected, the migrant is the one who poses a potential threat.”32)Meriam Chatty, “Migranternas medborgarskap” (Ph.D. diss., Studies in Political Science, Örebro University, 2015), 40. ☞

The authors of “The EU-Migrant Debate as Ideology” write that they use the term EU-migrant “to describe the groups of vulnerable EU-citizens who make a living for themselves and their families by begging in Sweden,” though they add that they use that term for lack of better, generally accepted alternatives and because they are discussing precisely the configuration of the debate itself.33)They maintain that the debate must concern who has the right to rights and which responsibilities come with the rights that exist within a certain social order.

——Hanna Bäckström, Johan Örestig, Erik Persson, “The EU Migrant Debate as Ideology”, Eurozine, June 15, (2016), 2. Accessed April 26, 2016, www.eurozine.com/articles/2016-06-15-orestig-en.html. Designations create or shore up underlying values. By using given designations I involve myself more actively in the hegemonic structure that I’m already unconsciously involved in. This also makes it clearer how the language of hegemony speaks through me. For instance using the term the Roma who beg can isolate those who beg to one ethnic group and have consequences that have the opposite effect than what the person using the term intended. The EU-mobile is another term that came into use in 2013 among critics of the designations of migrants. Another designation is guest-beggars (similar to guest-workers), used since more than 90 percent are only here for shorter periods, for reasons that are nearly exclusively financial. Leif Eriksson, researcher of global studies, writes: “Is this about citizenship, i.e. the status as Swedish citizen, or is it more about ‘citizenry’, i.e. some manner of active participation in community life. What does it mean in practice that also poor, vulnerable EU-migrants are EU-citizens? […] In practice these and other categorizations determine which rights one is granted.”34)The passage continues: “Is ‘inhabitants’ a more or less inclusive term than citizens? Is an EU migrant living in an illegal encampment one of the city’s inhabitants? So-called ‘undocumented’ migrants have a legal right to healthcare and schooling. Poor EU citizens aren’t included in the term ‘undocumented’ migrants and thus aren’t included in the legislation in question. In practice these and other categorizations become defining for which rights one is granted. In 2015 the city of Gothenburg established that the holders of rights are all who ‘live in the city’, but in 2016 it changed this to all ‘inhabitants’. The question of if this means that the circle of holders of rights has been limited has yet to be answered.” Leif Eriksson, Från elefanten i rummet till kanariefågeln i gruvan – om socialt utsatta EU-migranter i det svenska folkhemmet, Mistra Urban Futures Report, 2015:04, (School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg): 44.

Reasonably the political situation demands that the begging and giving happening on the streets be discussed, but it also leaves open the question: Where does the political begin and end? The authors of “The EU-Migrant Debate as Ideology” begin their reasoning with “Societies are more than an assembly of bodies, linked in mutual dependencies. They are also cultural systems,”35)Örestig, Bäckström, Persson, 2. thus they are letting us know, both what the point of departure must be and how complex the political situation is.

Over the course of the conversations I’ve had since 2011 with both those who give money and those who ask for money on the streets, a broad spectrum of various life conditions has emerged. Many different people beg. They don’t just come from the EU, there are also people from extra-European countries who come to Sweden and beg.

If the act of begging is what defines “beggars” the next question must be: What is the difference between begging and asking for help?36)Agnevik, Danielsson, 9. And if begging is an act of necessity, is the related act – giving – an act of charity? I maintain that begging can’t be discussed without also discussing giving – the images that are put into play with these actions are images that are generated within the same framework and are dependent on each other. This is why I have framed begging and giving as acts, looked at them as actions within a system and at what images these actions generate, even if who performs these actions obviously matters too.37)Hans Swärd, professor at the School of Social Work at Lund University writes: “If the issue is framed as one of safety and security for citizens in the public space, a reasonable solution might be to turn the beggars away from spaces where many citizens circulate. If the issue is framed as one of dire poverty, a reasonable solution could be to open shelters and soup kitchens to counter cold and hunger. If the issue is framed as a structural problem, a reasonable solution would be to take structural measures to eradicate poverty and discrimination.” “Den nya utsattheten – om EU-migranter och tiggeri”, Socialmedicinsk Tidskrift, Vol. 92, No. 3, 2015: 280. Accessed April 26, 2016 http://socialmedicinsktidskrift.se/index.php/smt/issue/current. One way or another everyone tries to create a strategy to manage their existence. People network and organize, that is one way of managing living together. That is one way of answering to a social system. “Begging” can be seen as such a response. In the self-organized civil society – the mobilization that has taken place in response to the situation of those who beg – “giving” is one response. Both acts reveal agency as well as deficiencies in a system. That is why I mainly use designations that pertain to the acts themselves – except in a few cases where some other term is relevant to the situation – “giving” in relation to “begging”.

1.4 Research Questions

How can one make visible the new situation regarding the begging and the giving? The number of articles about “beggars” increased seventeen-fold during the more than five years I worked on this subject. This bears witness to an increase in the number of people begging – from about a thousand people in 2011 to about five thousand in 2015 – but also to a need for expression in the general public. The social climate is changing and this can be seen and felt.38)I searched the Swedish newspaper database Retriever Research for articles on “beggars” and found that in 2011 there were 470; in 2012: 793; in 2013: 1,836; in 2014: 7,044; and in 2015: 7,699.

——The number of articles on “beggars” has multiplied by seventeen in four years. Professor Hans Swärd, who researches poverty, social problems, homelessness, social work and the history of social work, has done a similar investigation: “The number of begging people who’ve come here through free movement is estimated to be 4,000–6,000 people (in all of Sweden) in 2015, compared to about 10,000–30,000 undocumented migrants, and about 34,000 homeless people.” “Den nya utsattheten – om EU-migranter och tiggeri”, Socialmedicinsk Tidskrift, 269.

——In regards to the attention media has paid the issue Hans Swärd concludes: “Despite the issue having garnered attention, the level of knowledge is far from comprehensive.” He also writes: “We see the stranger through the eyes of the majority culture and base our assumptions on visible conditions, temporary behaviors, race or physical markers. The physical proximity of the situation to our daily lives along with lack of knowledge has meant heightened drama, which to some extent explains the heightened attention.” The visibility of those who beg has been given as a reason for why their presence is so frequently discussed and for the drama it causes, but their visibility also makes me visible – as I write above in “The First Encounter”: The act reveals me to myself as well as to my surroundings – the actions of both fall outside of the social contract. Images are made out of acts and images in turn create actions. What has happened and is happening between two people on the street – the giving and the begging – shreds a social self-image, at least for those who give, How are images – and physical action – in turn connected to social image and body politic?

Regardless of whether those who give and those who beg interact with each other, if they are in contact or not in contact at all, most seem to have stories about and images of one another, and of what the other is like. My curiosity and my investigation is based on my own first encounter during which I realized that I didn’t even attempt to see – that I could see more together with others. Was my dead gaze an effect of some collective influence – how do “we” regard begging as an activity, how do we regard the beggar, and who are “we”? My initial research questions were: What images does the giving face? And I began to ask people who give. Parallel to this I posed the question: What images does the begging face? I asked people who beg. In part I wanted to know which given images were in circulation, in part I wanted to try to understand something about the motivations, ideas, affectivities, feelings, thoughts, and values that shaped these images. This resulted in two films that are presented as an installation where the viewer (the potential giver) sits in between, in the space or leeway where the follow-up question becomes: Which images are at play between those who give and those who beg? My first two research questions are posed in the work to the viewer, and subsequently returned to me – the researcher – who can then reflect, analyze and pose the next question. The next question is about using various practices to investigate how these “images”, collective, as well as individual, visual as well as linguistic – are put into play in society. Revealing images in this way is a performative act. ☞

As a giver I have linguistic privilege. Power is about a meeting of different forces and is built on an interplay, even if begging and giving necessitate one another, even if there is a negotiation about what is given in the transaction; however the gift is given and received, it isn’t a “free exchange”, or an “encounter”, it is deeply shaped by class, gender, culture, and other hierarchies of power. What is in the power of the person who begs? What is in my power? These are questions that deal with will, responsibility, action, but also impotence, powerlessness, and limitation.39)“What I can do means both ‘what is in my power’ and ‘what am I able to do’. How does my power relate to the various forms of power that surround me, that shape me and which I might frequently and without knowing it, be part of, shape, and participate in. What power systems does my power relate to, which types of power systems am I part of, etc.”

——From a lecture text that Fredrika Spindler, associate professor of philosophy, wrote for the exhibition “What question would you ask someone who is more powerful than you?” at Rinkeby Folkets hus, as well as a travelling exhibition in Sweden arranged by Riksutställningar titled: “4U!”, 2004-5. The text can be found in its entirety at: www.ceciliaparsberg.se/4u/index_main.html.

My next step was to investigate the premises for a giver to create space for agency and I do this in the work Body on Street. Here I don’t involve those who beg. It’s an investigation done in cooperation with other givers into how the situation is embodied in different social bodies. In other words: How can one’s subjective images of a situation involving a person who begs manifest in the body and in the street? And how can these images “manifest socially” on streets and in public squares? To date the work Body on Street has been improvised in eight different cities. It is a photographic demonstration intended to generate new images.

I have followed phenomenologist Sara Ahmed’s theories of the other. She describes how emotions are created between, bind, and connect bodies. She reveals to me how this dynamic space is a space for action. My next question then becomes: How can one portray this space of action that exists between the person who begs and the person who gives? It is portrayed in the dialogue-based choral arrangement with twenty-four participants. If a mutual action is staged – something which none of those begging or giving have previously done in this manner – can new images be conveyed between the participants? Can they be conveyed to the viewer who once again gets to inhabit the “in between” – the space between the two choirs?

1.5 Methodological Stance and Intent

1.

Apart from the study of the specific subject at hand, my research project is my artistic method and practice. As Mara Lee puts it in her dissertation on literary portrayal: “So far there are few methods within artistic research regarded as generally valid and shareable. It is hard to find a set of methodological rules that can be used by many. Our methods usually stem from and are rooted in our artistic practice, and thus the element of style becomes part of the method.”40)Mara Lee, När andra skriver; skrivande som motstånd, ansvar och tid, (Gothenburg: Glänta, 2014), 26. I have worked with methodological intent.

Throughout this entire project I activate my research questions together with other people. Often “the beggar” is referred to as if they are the carrier of “the problem” and thus also require a personified or collective solution, something the authors of the article “The EU-Migrant Debate as Ideology” are also critical of: “Rather the EU migrant appears as ‘a figure who embodies a life beyond the disciplined bodies of the well-behaved workers’. This figure is intimidating in the eyes of the ‘rule of law’ since it cannot be isolated from the ethnic group.”41)Örestig, Bäckström, Persson, 6. The authors maintain that the images ascribed to those who beg are the result of a prevailing economic structure, which must also be problematized, and they stress the importance of renegotiating and “to establish conditions for EU migrants to come forth as political subjects that social majorities not only speak about but, in the end, speak to.”42)Ibid., 9. How then, in practice, does one speak to? This is what the thesis as a whole aims to investigate, using my first encounter above as a point of departure. This is also what the research questions aim to investigate. I’ve been guided by my experience as a documentary filmmaker, action researcher, and with other field study over the years, in terms of what speaking and listening to might look like in concrete situations. The works that this text describes and which are shown on this website intend to further illuminate this practice within the discipline of fine art.

When the artistic work is done in concert with other people every situation involving another person is unique and necessitates its own negotiations over the image, over the ethical in the aesthetic presentation that is being created. To want to speak through images does not mean that it is doable, it often fails due to the questions being asked not being formulated in relation to the one who is expected to answer, they aren’t heard or understood, or aren’t relevant to the person being addressed. Space is vital for both parties and the process of negotiation can’t be too controlled, but still needs to have a certain direction. To speak to is a mutual process. This is why I think it necessary to go into this project with a methodological intent and to develop the method together with. To use art historian Claire Bishop’s description, I am “less interested in a relational aesthetic than in the creative rewards of participation as a politicized working process.”43)Bishop, 2. This includes an investigation of the aesthetic. Nor do I assume a specific method of image creation in this context, rather I begin by making visible and shaping the research questions. ☞

In my work I make use of concrete situations as well as experiences of encounters that then become tools to create a portrayal. “Practical knowledge, phronēsis, is a another kind of knowledge. Primarily, this means that it is directed towards the concrete situation. Thus it must grasp the ‘circumstances’ in their infinite variety.”44)Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, (New York: Continuum, 1989), 19. So writes the German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer.45)Ibid., 19. Here Gadamer refers to the words of Aristotle in a footnote: “Knowing what is good for one is a sort of knowledge.” Den Nikomachiska etiken, Första boken, transl. Mårten Ringbom, (Gothenburg: Daidalos, 1993). Phronēsis here means knowledge in which individual cases – situations – are judged in relation to context. A number of ethical and epistemological problems converge in field study of “strangers”, people from other cultural contexts or positions of power.46)According to a description in the journal Fronesis the term phronēsis comes “from ancient Greece and indicates a practical form of knowledge. Aristotle differentiated between the technical form of knowledge ‘techne’, which was instrumental, the logical form of knowledge ‘episteme’, that was separate from action, and the virtue of wisdom and reflection, phronesis, which was self-motivated. The term phronesis expands onto a critical knowledge that makes it possible for us to transgress the arbitrary boundaries of the day for what is politically and intellectually possible.” “Om Fronesis”. Accessed April 26, 2016, www.fronesis.nu/om-fronesis. And yet another question might be formulated against the backdrop of all of this: How can the images of those who beg and those who give be problematized in order to generate new images – in such a way that image makers or mediators also have to look at themselves, their knowledge, their complicity? This question also brings one face to face with the frame within which the production of knowledge takes place. My methodological intent contains elements of unlearning, as well as the generation of new images. The individual encounter may be unique, particular, but can also be seen as part of a larger pattern. In this sense my own shortcomings also constitute an important basis of experience. Thus the artistic practice involves a constant labor of destruction, in part because the destruction of given images (prevailing normative images) is connected to the possibility of creating new ones, in part because the intention is to try to move outside of a given framework. My intent is also to use works of art to create points of contact with other disciplines, in practice and in theory. A project such as this isn’t possible without examining one’s own power structure, the one I am part of. This may be the most difficult aspect. Even with the best intentions a presentation can’t escape also being a representation of the participants as “those who beg and those who give”, but in this process, as well as in different forms of presentations, I have attempted to open up spaces for participants and viewers to reflect and participate. In the practical procedure I also try to separate my subjective intentions by investigating and portraying.

2.

Every form of portrayal has its own process, method and model. The following is a frame for various working processes and it has four corners.

- A way of destroying47)Inspired by Louise Bourgeois’ notes in Deconstruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998). – the image of the image; that is the imagined image (ways of seeing as part of a prevailing, normative image, the image belonging to the culture). This is about self-reflection and revealing oneself as a bearer of dominant norms and working through these images. To paint (or in a different execution: text, photo, performance); a self-portrait – a self-image as a revelation of me as the person who sees and depicts in order to declare a certain position.48)In this project for instance the short recording of the first encounter is what reveals me. After this, revelations happen for each step of the thesis. Self-reflection that also leads to revelation is perishable. Self-reflection is the trampled track next to the road. The cursive passages in this text are a selection of self-reflections. The destruction takes place during the time it takes to understand and can involve a personal reckoning with a past, to see old insights in a new light.49)Insights that have been reached in a previous situation are contemplated anew in the next. But they can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from self-images, understandings and old, sanitized images that limit. Insights must also be challenged, as Hans Larsson points out “How infinitely much lies not in a person’s view of themselves? His conscious reflection can hardly include anything but a few traits, a few needs in their most general direction and not the particularity they have and that everything will depend on.” Hans Larsson, Intuition, (Stockholm: Dialoger, 1997), 52.

- A will to see – to reach, listen with all senses, reflect, translate. To set up encounters and find out what opens up. To seek contact – a mutual desire to see and be seen. The quest for horizontality, there is a de-objectification in the process of speaking to. Reflecting over an aesthetics of distance and an aesthetics of proximity. Zooming out and seeing larger contexts, power structures, frameworks – framing.50)A friend of mine tells me that her seven-year-old son has brought home two drawings from school. The teacher instructed the children to draw a self-portrait. He paints himself, his mom, and his dad. He shows the drawing but the teacher said – No, you were supposed to paint your self-portrait. He draws another: Himself, his mom, and his dad. A self-portrait is a form of self-image and this boy drew those closest to him as co-creators of his self-image. Perhaps he is saying that his image is a relational process where the image of the other is returned, reflected by the person, or those who look at him. Perhaps the fact that he was adopted from China matters here and hence he has an intuitive understanding of what it means to have a different look – image – than those who surround him. Perhaps drawing conveys what he can’t express to his teacher in words. Perhaps – if the teacher has an authoritarian outlook on teaching as well as image – this boy will eventually begin to draw like the others; a self-portrait like the face I see in the mirror. Because that is, “the right way to draw a self-portrait”. He is schooled in adjusting his way of seeing according to the prevailing consensus on how a self-portrait is drawn. But if the teacher can see outside of his accustomed frame, see what his drawing conveys – listen to the image, be open to learning, it is possible that his self-image can have a place next to the others, in school, in education.

- A movement inward and outward – images relate to each other in some way, the image can never be entirely new, since I can never leave or stand outside of the frame. But the images can be challenged in order to process them: to un-frame the framed. In part this also means a failure at seeing, understanding, and changing. In the contact that is sought with the participants lie the questions: how (ethics) and for what (aesthetics)? By suggesting meaning, re-evaluation, de-/re-interpretation the blindness to the frame may engage listening.

- An attempt to change – to differentiate and create a space for action. How do one’s own gestures relate to the gestures of the body politic? Which are the questions I want to pose, and does the work succeed in posing them and opening them up for the artist and the viewer? To frame the unframed space, may be the role of the artist. To un-frame the framed, and then activate the space, may be the role of the audience.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Notes

| 1. | ☝︎ | Sara Ahmed, professor of race and cultural studies, describes how shame can be experienced in a variety of ways: “Shame can also be experienced as the affective cost of not following the scripts of normative existence.” ——Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, second edition, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 107. |

| 2. | ☝︎ | Philosopher Luce Irigaray describes the necessity of air space in an encounter as follows: “Air that which brings us together and separates us. Which unites us and leaves a space for us between us. In which we love each other but which also belongs to the earth. Which at times we share in a few inspired words. Air, which gives us forms from within and from without and in which I can give you forms if the words I address to you are truly destined for you and are still the oeuvre of my flesh.” Luce Irigaray, I Love to You: Sketch for a Felicity Within History, (London: Routledge, 1996), 148. |

| 3. | ☝︎ | This account of philosopher Jakob Meloe’s theory is borrowed from a lecture by Professor Ingela Josefsson in a postgraduate course in epistemology at STDH, Stockholm University, September 21, 2011–February 6, 2012. |

| 4. | ☝︎ | Ingela Josefsson, doctor of Scandinavian languages, was the vice-chancellor of Södertörn University until June 2010 and is Professor of Working Life studies at the Center for Studies in Practical Knowledge at Södertörn University. Among other things she maintains the importance of tacit knowledge or practical knowledge and says in an interview that she noticed that: “A gap has formed between what one could call academic praxis and the praxis in practice.” Practice-based knowledge is a term developed in the Anglo-Saxon world for praxis-based research but Ingela Josefsson and others choose the Swedish term praktisk kunskap, which they translate as practical knowledge in English (rather than the term tacit knowledge which was used initially). It aims to be professional or working life knowledge. Though the terms may seem synonymous, these are separate discourses. Markus Prest, “Teorin måste utformas på praktikens villkor”, Ikaros 3.10 (2010). Accessed May 9, 2016, www.fbf.fi/ikaros/arkiv/2010-3/310_prest2.pdf. ——During the same Ph.D. seminar Josefsson refers to Norwegian philosopher Hans Skjervheim who writes: “Engagement is a foundation of human existence, it has to do with what Heidegger calls Geworfenheit (thrown-ness). What we can choose is what we want to engage in, or we can let others choose for us.” Hans Skjervheim, Ian Hamilton, and Lillemor Lagerlöf, Deltagare och åskådare. Sex bidrag till debatten om människans frihet i det moderna samhället, (Stockholm: Prisma/Verdandi, 1971), 21. |

| 5. | ☝︎ | All works are shown together in a travelling exhibition: At Skövde Konsthall, Varbergs Konsthall, and Skellefteå Konsthall 2015–17. There have also been a number of exhibitions and street screenings of individual staged works. In connection with the dissertation there will be an opportunity to see the works at Skellefteå Konsthall, starting October 30, 2016, which is one of several exhibition windows for the material in the thesis. |

| 6. | ☝︎ | All fall under the umbrella term participatory art. They are: A documentary participatory-performative film, Enjoy Poverty by Renzo Martens, a documentary participatory-performative film installation, Kropp – Erfarenhet – Kunskap [Body-Experience-Knowledge] by Ioana Cojocariu, a public space-performance, Persondesign, by artistic duo Bogdan Szyber & Carina Reich, a participatory-public-installation, Lights in the City by Alfredo Jaar, and a site-specific action painting and cutting by AKAY & KlisterPeter. I use these terms to show how contemporary art uses and compiles various practices and methodologies. |

| 7. | ☝︎ | Performance is an art form that can be part of works in various ways. Stimulated by my colleagues I investigate possibilities in practice, and have done so since the early 1990s. My background was in painting during the 1980s. I was active in video art in the 1990s, in the tradition that involves a performance in front of the camera in a closed room, alone or with a participant, which is then screened as an art installation. My practice later transitioned to participatory performative staged works and action documentary (www.ceciliaparsberg.com). Since the turn of the millennium I’ve worked with participation in different forms, some of these can be designated variations of delegated performances, which is a term used by Claire Bishop. But these also differ from each other, see further discussion in the text. This thesis work contains the staged works What Images does the Giving face? & What Images does the Begging face?, chapter 2, Body on Street, chapter 4, and The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving, chapter 7, where performance forms a foundation for my work. In these participatory performances I am the employer, I pay all participants and everybody knows that this will become a film for an art installation. I am describing art movements and –isms so that we know that we mean the same thing while talking, but it is not within the scope of my thesis to analyze them. Much like the term “art” I use “performance” as an open term. ——The meaning of performance in relation to performative acts is analyzed by, among others, artist and art theorist Barbara Bolt, she refers to philosopher of language John Langshaw Austin, Judith Butler, Jacques Derrida and others. ——Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?” PARSE 3, (2016). An older and shorter version can be found online: “A Performative Paradigm for the Creative Arts?” accessed May 9, 2016, www.herts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12417/WPIAAD_vol5_bolt.pdf. |

| 8. | ☝︎ | Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The politics of performance, (London: Routledge, 1993), 148. |

| 9. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 148. Phelan positions the constative (self-referential acts of speech – findings) in contradiction to the metonymic: “Metonymy is additive and associative; it works to secure a horizontal axis of contiguity and displacement.” (Ibid., 215). She also maintains that the performative displays independence from an external reference in present actions. |

| 10. | ☝︎ | “Just as her body remains unseen as ‘in itself it really is,’ so too does the sign fail to reproduce the referent.” (Ibid., 150). |

| 11. | ☝︎ | In another example Phelan discusses the works of Sophie Calle, an artist who works with stories and who “is increasingly moving toward performance”, here on a work at the Isabella Gardner Stewart Museum in Boston: “The descriptions fill in, and thus supplement (add to, defer, and displace) the stolen paintings […] the interaction between the art object and the spectator is, essentially, performative – and therefore resistant to the claims of validity and accuracy endemic to the discourse of reproduction. […] The description itself does not reproduce the object, it rather helps to restage and restate […].” (Ibid., 147). ——According to my interpretation Phelan is talking about how the absence of objects together with the stories of the vanished objects create images in the viewer, a performative act takes place between art object and viewer that generates new images. |

| 12. | ☝︎ | In the mid-1990s a particular kind of performance emerged, described here by Claire Bishop: “Although this trend takes a number of forms, […] all of this work […] maintains a comfortable relationship to the gallery, taking it either as the frame for a performance or as a space of exhibition for the photographic and video artefact that results from this. I will refer to this tendency as ‘delegated performance’: the act of hiring non-professionals or specialists in other fields to undertake the job of being present and performing at a particular time and a particular place on behalf of the artist, and following his/her instructions.” Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, (New York: Verso, 2012), 222. ——One example is the work of Santiago Sierra, in which he hires workers to complete simple tasks in the exhibition space during the time of the exhibition, such as hold up a wall that’s about to fall, or part of a wall. His performance alludes to the socio-economic system. “Although the artist delegates power to the performer (entrusting them with agency while also affirming hierarchy), delegation is not just a one-way, downward gesture. In turn, the performers also delegate something to the artist: a guarantee of authenticity, through their proximity to everyday social reality, conventionally denied to the artist who deals merely in representations.” (Bishop, 237). Bishop addresses a number of variations on delegated performance and discusses these in chapter 8. ——The works by Ioana Cojocariu and Szyber & Reich that I mentioned can be termed ‘delegated performances’ according to Bishop’s definition, as can my works What Images does the Giving face? & What Images does the Begging face? and The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving. ——The ways in which the performance of the 1990s differs from that of the 1960s and ’70s is also interesting in this context, and as Claire Bishop puts it: “Artists in the 1970s used their own bodies as the medium and material of the work, often with a corresponding emphasis on physical and psychological transgression. Today’s delegated performance still places a high value upon immediacy, but if it has any transgressive character, this tends to derive from the perception that artists are exhibiting and exploiting other subjects.” (Bishop, 223). The examples of staged works that are addressed in the thesis also exist within and aim to discuss this kind of drawing of ethical and aesthetic boundaries. |

| 13. | ☝︎ | Relational Art is a tendency in contemporary art that art critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud highlights with his book Relational Aesthetics, (Dijon: Les Presses Du Reel, 1998), and that has influenced my artistic practice, But with my engagement in social and policy issues my practice is closer to what Boris Groys describes: “The phenomenon of art activism is central to our time because it is a new phenomenon – quite different from the phenomenon of critical art that became familiar to us during recent decades. Art activists do not want to merely criticize the art system or the general political and social conditions under which this system functions. Rather, they want to change these conditions by means of art – not so much inside the art system but outside it, in reality itself.” Boris Groys, “On Art Activism”, E-flux journal, 56, (2014): 1. Accessed April 30, 2016, www.e-flux.com/journal/on-art-activism. |

| 14. | ☝︎ | Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?”. |

| 15. | ☝︎ | “The essay argues that the performative needs to be understood in terms of the performative force of art, that is, its capacity to effect ‘movement’ in thought, word and deed in the individual and social sensorium.” (Barbara Bolt, “Artistic Research: A Performative Paradigm?”, 134.) |

| 16. | ☝︎ | “The street photographer can be seen as an extension of the flaneur an observer of the streets (who was often a writer or artist)”. Susan Sontag, On Photography, (London: Penguin, 2008), 55. ——Street photography is “conducted for art or enquiry that features unmediated chance encounters and random incidents within public places. […] Street photography can focus on people and their behavior in public.” “Street Photography”, Wikipedia. Accessed May 14, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Street_photography. |

| 17. | ☝︎ | A workshop has been arranged for each exhibition together with participants from that town, the photos that are generated are then displayed in the exhibition space together with the others from the series Body on Street. |

| 18. | ☝︎ | Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback, Att tänka i skisser, (Gothenburg: Glänta, 2011), 12. |

| 19. | ☝︎ | Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback explains this relationship in Att tänka i skisser. She writes: “The longstanding philosophical dispute between logos and mytos, reason and myth, is primarily a struggle between idea and image, between abstraction and fiction, and thus between two types of distancing from the real.” (Ibid., 7). |

| 20. | ☝︎ | Anna Bodin, “Jag vill översätta det fantastiska ljuset till musik”, April 17, 2016, Dagens Nyheter. Accessed April 26, 2016, www.dn.se/arkiv/dn-kultur/jag-vill-oversatta-det-fantastiska-ljuset-till-musik. |

| 21. | ☝︎ | “[…] key examples might include Gillian Wearing, Artur Żmijewski and Phil Collins.” (Bishop, 226). |

| 22. | ☝︎ | “What I am calling delegated performance in all its contemporary iterations (from live installation to constructed situations) brings clear pressures to bear on the conventions of body art as they have been handed down to us from the 1960s.” (Ibid., 226). |

| 23. | ☝︎ | “On the Production of The Chorus of Begging and The Chorus of Giving”. |