4.1 Politics of Waiting

1.

The streets transport a flow of bodies, people in constant motion, in and out of social activities, an ongoing social choreography. And there, between walking legs, I catch a glimpse of bodies kneeling on the ground in various positions, bodies that spell necessity and need. How do the bodies acquire their grammatical form?1)“For Aristotle the soul designates the actualization of matter, where matter is understood as fully potential and unactualized”. Judith Butler interprets Aristotle’s De Anima in her book Bodies that Matter, (New York: Routledge, 2011), 32.

——The body is matter. Butler claims that matter doesn’t appear without the schematic: form, shape, expression, and syllogism. The body appears in a certain grammatical form within a discourse of power throughout history.

The giver is standing and the begging person is kneeling, this is happening on a pedestrian mall in central Stockholm, in free movement Europe, in a Europe where you are free to move as you choose. In his dissertation Kent Sjöström differentiates action from activity: “My assumption is that the body on and off stage is intentional, even though physical activities usually considered unintentional aren’t necessarily understood in these terms.”2)Kent Sjöström, Skådespelaren i handling; strategier för tanke och kropp, (Stockholm: Carlsson, 2007), 151. He claims that there are no unintentional movements, but that the intentions of certain movements are unconscious. The difference depends on why any given movement is made, something that can be understood once an activity is put into context, but not necessarily from the movement in and of itself (which Ioana Cojocariu’s film makes clear, as described in paragraph 8 below). Kneeling can be seen as a prayer position in which somebody humbles themself in the face of something larger, but also as a plea, and as suffering in the face of something that has hit and continues to hit – systemically.

2.

On February 14, 2013 Swedish morning paper Dagens Nyheter ran a bold headline across half a page: “I can’t stand seeing beggars on the street any longer”3)Kerstin Vinterhed, “Var finns ambitionen att hjälpa Stockholms tiggare?” Dagens Nyheter, February 14, 2013. Accessed April 27, 2016, dn.se/debatt/stockholmsdebatt/var-finns-ambitionen-att-hjalpa-stockholms-tiggare. In the article Kerstin Vinterhed writes: “Because after all there is a mutual humiliation of both the person begging and the person giving – or not giving. A humiliation of those – who like me and most people in this country – have participated in building a society in which begging and charity has been replaced with the right to aid.” But if that’s the case, have we not also participated in breaking down that right? She writes: “a humiliation of”, and this implies that those who beg and those who are expected to give are humiliated by a system, by a financial and political matrix.4)A matrix is a template that produces structures (patterns, content, meanings beyond the overt message, actions, incidents, and other human contexts). But what kind of template is this? In a world that has experienced the nuclear bomb, the growing gap between the developing world and the industrialized world, environmental destruction, and the dumbing down of the capitalist industry of consciousness there are discussions about how knowledge is produced, so writes Sven-Eric Liedman, who studies the history of ideas and he stresses: “For Marx it is obvious that the large shifts have to do with conditions that lie beyond human consciousness. Consciousness doesn’t create history. In relation to the greater processes, individuals, with their calculations and schemes, are coincidences […] History flows through our lives. The currents are below the surface.” Sven-Eric Liedman, Humanistiska forskningstraditioner i Sverige, (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1978), 48–54. She can’t stand it anymore, but where can she go? She turns to language, to the political. She has that power, is part of a culture that takes for granted that one’s voice can affect prevailing policy. Still, she says she feels powerless. What should she do? She can’t understand what’s happening around her, to her, in relation to those who beg.

I can’t stand my own powerlessness either, I’m not sufficient, I can’t embrace, I stand crestfallen in front of you. Who am I if I don’t give, what should I do, if I’m alone, are there others like me, can I become less powerless by becoming a “we”?

Many proclaim that they can’t stand it and don’t speak, don’t address, converse, indict. What would it do to me if I didn’t make images, if I were to stop naming and describing what I see around me? What would it do to me if I ignored those who beg? What does it do to me to not give to the person who asks to receive?5)“Since my aim is to ask about the relationship between what tragedy shows and what we find intuitively acceptable”. Martha Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness, (Aeschylus and practical conflict), (New York: Cambridge University press, 1986), 26. It concerns me, but is it just a selfish concern? Anne Carson writes: “To combat the resistance of language you must keep on talking, my analyst said.” Regardless of what I feel that I can’t stand, I am part of the hegemonic order that has the privilege of being heard in society and that benefits from the prevailing system, which I also accept to some degree and am “employed by”. The person begging does speak, but only after being spoken to by the person included in society. I’m looking for more than just being aware of the gap. I rephrase the question: What would ignoring the begging do to me?

I am damned if I give and damned if I don’t give. I can’t stand being a part of this “we”! What is it doing to me? To my body and my soul? By dint of my actions I am part of a collective movement, I get answers I can’t be without, questions I can’t act without, can’t ignore, regardless of if I accept them or not. I don’t actually want to stand it, because the inescapable fact remains that what my senses encounter isn’t an image, it’s not an idea, it’s a shared existence. It’s a tragedy. The pattern of the human condition. ☞

I find myself performing new gestures that don’t feel voluntary – they’re not voluntary, yet they are performed by me, by my body. I also try to understand what structure would have to collapse for my existence to become intelligible and manageable again.6)“Art will mediate and adorn, and develop magical structures to conceal the absence of God or his distance. We live now amid the collapse of many such structures, and as religion and metaphysics in the West withdraw from the embraces of art, we are it might seem being forced to become mystics through the lack of any imagery which could satisfy the mind.” Iris Murdoch, The Fire and the Sun, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), 88. Iris Murdoch writes that “Obsession shrinks reality to a single pattern”, then further describes how ideas need to be teased apart back into thoughts for it to be possible to see what’s really separate and what might yet again be seen as connected.7)Ibid., 79. But how? Tore Nordenstam suggests a way of seeing: “The expressions and the parts of the pattern are woven into activities, that in turn have their determined place in the whole we call a culture, or way of life.”8)Quoted from a seminar with philosopher Tore Nordenstam and Ingela Josefsson, professor of Working Life studies, in the course Kunskapsfilosofi 2, DI, Stockholm, March 22, 2013. Is the begging person part of a pattern? What patterns are drawn across the urban landscapes of the cities? Hannah Arendt writes: “It is because of this already existing web of human relationships, with its innumerable, conflicting wills and intentions, that action almost never achieves its purpose; but it is also because of this medium, in which action alone is real, that it ‘produces’ stories with or without intention as naturally as fabrication produces tangible things.”9)Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 184. What frustrates me, and others, is that they, with their request to get, to get to share, spin their thread into the web, hence my question to the person begging: How can you become successful? In this context the question points to an impossible equation. As Sara Stridsberg put it: “Begging is done by the one who owns nothing and who asks for charity and it’s an entirely linguistic matter that becomes a worldly matter (you wife or your husband is not begging if she or he asks for a sandwich, you are not begging when you ask your boss for a raise). Begging is done by those without rights, a pet begs, those whose demands are not considered legitimate.”10)“Sara Stridsberg”, Sommar i P1, Sveriges Radio, July 21, 2011. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/126264?programid=2071.

Stridsberg emailed me the quote and I am using it here with her permission. This is the context in which to understand Kent Sjöström when he writes that he assumes the body to be intentional both on and off stage. The begging person wants their posture to bring them success in begging, an improvement. Begging happens within a social structure, within a political system and the begging person may achieve some improvement – but is that enough? What kind of change is sought and demanded by those who exclaim that they can’t stand it anymore? How do you become a successful beggar in Sweden? Begging as well as giving are gestures with which something is exchanged, related gestures in an urban environment. In a system that has finally turned ironic on people. I share the frustration that Vinterhed expresses: “I can’t stand it.”

And I wonder to what extent I am a cog in the machinery, my question will never be answered, but between the poles of empowerment and powerlessness there is a tension. My question is expressed in my posture.

3.

One thing that unites my approach with that of Carina Reich and Bogdan Szyber in their project Persondesign (which I describe in further detail in chapter 2) is a sense of shame and guilt in the face of the begging person. On their project website they describe this as one of the driving forces behind their project.11)“Beggars Saturday & Persondesign”. Accessed April 4, 2016, http://reich-szyber.com/en/portfolio/beggars-saturday-persondesign/. There is a socio-economic imbalance to projects like ours, in which a privileged artist backed by taxpayer money stages an interactive situation with someone who lacks those same privileges. A situation in which one party doesn’t, or can just barely, participate in the discussion in the exhibition space (whether that is a blog, or a white cube, or some other space). There is a “we” in both our investigations that poses questions about a problem that lies partially outside the body but is also “felt in the body” and not just as a feeling, but also physically, in terms of positions. I call this my social physicality. Phenomenologist Sara Ahmed describes how this can be expressed in one’s body: “The very physicality of shame – how it works on and through bodies – means that shame also involves the de-forming and re-forming of bodily and social spaces, as bodies ‘turn away’ from the others who witness the shame.”12)Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, second edition, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 103. This “we” is part of the same system and both projects frame the questions in similar ways. One might say that we have the same framework – the political discourse in Sweden. And that our reactions to Vinterhed, as well as our actions, are similar. Sara Ahmed writes how shame can feel like being exposed while also trying to hide, to cover up the act. It’s like being watched while failing, becoming visible when one isn’t ready to be revealed. “To be witnessed in one’s failure is to be ashamed: to have one’s shame witnessed is even more shaming. The bind of shame is that it is intensified by being seen by others as shame.”13)Ibid., 103. These feelings can be triggered in a giving-to-the-begging situation. I am a participant in the prevailing economic system, as a subject I am active to some degree in the system that causes poverty. The authors of the article “The EU Migrant Debate as Ideology” describe how an economic system – such as the Swedish welfare state – gives rise to a moral economy.14)Bäckström, Örestig, Persson, 3. “The moral economy signals that the key to social rights is and should be citizenship and labour market participation.” They refer to the idea of debt playing a central role in the abstract political community.15)Bäckström, Örestig, Persson, 4. A theory that they credit to American political scientist Kathleen Arnold, Homelessness, Citizenship, and Identity, (Albany: SUNY Press, 2004). It’s a reaction. Sara Ahmed writes: “So when we recognize ourselves as shamed, that self-identification involves a different relationship of self to self and self to others from the recognition of ourselves as guilty”.16)Ahmed, 105. Both the authors of the article, Örestig, Bäckström, and Persson, as well as Sara Ahmed note that the reaction can be expressed so that the experienced shame is deflected – in defense of the unpleasant feelings it provokes: “In shame the subject may have nowhere to turn.”17)Ibid., 104. Örestig, Bäckström, and Persson describe it as follows: “However, there is also a more fundamental and underlying problem in the logic of reciprocity, which is revealed when someone ‘fails’ to live up to expectations, or is accused of refusing to do so. Then the expectations of reciprocity are quickly transformed into a debt – which gives the ‘creditor’ a potential position of power.”18)Bäckström, Örestig, Persson, 4.

But Sara Ahmed finds an opening; while guilt refers to wrong-doing, shame can lead to an intimate relationship with myself, shame is questioned by shame: “I may be shamed by somebody, somebody whose view ‘matters’ to me. As a result, shame is not a purely negative relation to another: shame is ambivalent.”19)Ahmed, 105. To feel shame and guilt may also be a way of not accepting the state of things and letting it prompt one to stage the questions one has. Vinterhed does this by writing, Reich & Szyber by their participatory performance and I do it by posing my questions about what images the begging face as they beg, and what images the giving face when they give.20)See further reasoning regarding hierarchies of power in chapter 5.1: “Private Business, Public Space”, paragraph 5. A new configuration is slowly taking shape in me. What images create this powerlessness?

4.

I don’t know who you are. Through my acts I display an image of myself, but the image doesn’t resemble me. I bend over, no my body bends over, toward you, I don’t really want to, I want you to stand up to that which has trodden you down. A structure is speaking through me, owns a part of me, rules my body.

The structure or matrix emerges in the image due to the actions of those who beg. I see various grid patterns around me.

The relation between the spatial and the social situation isn’t temporary. Our transaction on the streets, in the cities, isn’t temporary – it follows spatial and social patterns.

How can so many bodies be sitting on the city streets? Some are begging, others plead, some sing, some seem to just sit there with a cup in front of them. What political interests bind the body in such a position, the many bodies in many different variations of positions: sitting, kneeling, not upright in the climate of the street, the environment that plays a part in how our bodies can move, position themselves, express themselves. I feel addressed by them, but also accused by the matrix that holds bodies in this position.21)“Rather, we find ourselves born into communities in which the available ways of acting are largely laid out in advance: in which human activity takes on different […] ‘forms of life’ […] and our obligations are shaped by the requirements of those forms.” Stephen Toulmin, Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity, (New York: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 23. The invisible bars, horizontal and vertical, that are woven through our bodies and render them powerless. The impoverished bodies don’t just exist physically on the streets, but also in the minds of the standing and walking people, in the language that never dies down – in bodies, through and out. The matrix rules those of us who are upright – and walking – and we move together as a flow, we express ourselves together, like the swarms of bees, we swarm about and around, directed by attractions and desires.

The person lying prostrate on the street when it is five degrees centigrade below freezing, with their hands against the ice-cold ground is not part of the swarm, she stubbornly remains lying there. I can feel her in my body, I don’t want to leave. This woman could have been my mother.

Each of us who walk and are upright could step forward, stand next to the prostrate figures and not move. We could stop walking, moving with the flow, we could stay by those who’ve already been silenced and excluded. While waiting, enduring, would the invisible threads of the matrix lose their elasticity, go slack, collapse? Would that kind of demonstration break the ongoing conversation? Like when a thousand residents of Dharavi, the largest slum in Asia, step out of their homes and block the flow of the city by sitting down and fasting.22)“Dharavi Residents Stage Anti-Government Protest”, DNA India, June 12, 2012. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report-dharavi-residents-stage-anti-govt-protest-1701162. ☞

I sent a question to one of my younger friends, a 26-year-old who has done a lot of activist work in Sweden. A question about if those of us with power, us upright people, could stage a quiet, physical, synchronized action of will and power – all the upright bodies in the city placing themselves by the sitting bodies in solidarity. I was curious if she thought this was a viable action. Here’s what she answered:

“Hi Cecilia, my first reaction is that it would be a good action. When I think about it further I try to imagine what it would be like to be a begging person and have a whole bunch of other people come and sit next to me. I’m not sure how that would feel. One would have to make clear that this was a protest. The second thing that comes to mind is who the action is directed at, the current linguistics perhaps, how could one dial that in, push it further? I can be a bit square when it comes to checking: a.) What an action does for those one wants to help/whose situation one is protesting/those who suffer the worst consequences of the order one is protesting. b.) What entity the protest is directed at and if it will reach it. So that it doesn’t just serve those who are involved in the actual protest (unless that’s the point, which it can be at times). Like, how does this jibe with the actual situation and what does it do with the actual situation, what does it leave behind? I also like to ask myself ‘What do I, the protester risk?’ Very broadly speaking I think the more, the better, but that doesn’t necessarily have to be the case. One very palpable thing that one would achieve if one staged a flash mob as described above is that those begging might think one was making fun of them/parodying them/using them for something and that passers-by would think ‘Who are these crazy activists/artists’ and end up even more blocked and angry. That is a worst-case scenario, but my first reaction, like I said, is that it could be both an interesting and good thing, that if executed ‘correctly’ could create an opening, or nudge something. Best regards, Karin.”

In other words it could be an intentional action of social bodies in the body politic in order to influence policy, but how and in what direction? How can powerlessness be turned into constructive action?

5.

The beggars themselves already are and display facts on the ground, they are committing a political action, they speak through their silence; through (performative) body language. It is passive resistance; the beggars are expressing a kind of politics of waiting, a forced demonstration. A demonstration that is about and that expresses an ongoing passive unemployment activity. A demonstration of an exclusion that makes visible how a We have excluded a Them. Their begging is directed at all passers-by, regardless of position of power, skin tone, and gender. It demonstrates to us – who are working or have the option of finding work – and makes us complicit in a suppression, in a policy that has excluded certain people. On her radio show Sara Stridsberg says: “And for one single, vertiginous moment, an entire world order is thrown into question, a person’s outstretched hand is very common and negligible. It happens all the time, everywhere, you forget it, and you can’t forget it, the hand.”23)Stridsberg, www.sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/126264?programid=2071.

It’s almost as if this demonstration has created a “we”. One feels like one belongs to a different category, one that one might not have previously considered. But I am part of the European body politic, as is the begging person on the street. The begging person is excluded from belonging in various ways: From schooling, work, health care, and other things that should be part of, other things that usually belong in, a social community. Poverty is a political condition and that political condition affects us all. What happens in the streets makes visible the systemic failures of European policy. Inequalities between individual people are upheld by the tension between the system of the individual nation state and the EU.

6.

On August 21, 2013 I pass this woman on Götgatan, as I’ve done many times before. She is one of those I’ve previously interviewed with Laura as an interpreter and we greet each other with some familiarity. She has a puppy now. We exchange a few words. I pet the dog and stay for a moment. I ask if I may photograph her with her dog. She gets up. She wants to show what it’s learned. The dog obeys her commands, lies down and is rewarded with praise and a treat.

The hierarchy becomes apparent; she stands up to feed her sitting dog, I stand up and give her money when she is sitting. We, our bodies, how we perform gestures, form patterns. We are images in a pattern that is continually being drawn. Afterward I don’t quite know what to do with all the conflicting emotions that this interaction engendered. I go up the attic and paint.24)My educational background is in painting, I studied for two years at the Hovedskous art school in Gothenburg, where we did live figure drawing every day. After that I was accepted at Valand Academy where I studied from 1986 to 1991, but I haven’t painted much since then, only during periods when I need to work through experiences, or remember, or when it is the most relevant production technique in a certain project.

I need to engage my entire body. The size of the canvas corresponds to my height and the span of my outstretched arms, the movement activates me physically and mentally. I recall how I – many years ago – used to do live figure drawing and it wasn’t until I gauged my own body for the position of the model, imitated them physically, that I could draw the model’s body. Does live figure drawing develop a capacity for empathy? Perhaps to some extent, but it’s less about seeing oneself in the other’s body and in their situation, than finding the other’s physicality in your own. It doesn’t result in a painting of a hierarchical order, of how we figure in a structure, rather it results in a face – something is unique in every individual – her face – but not quite; as rendered by me.

Later, when I look at the painting I see different moods reflected in the face. It has become a nonlinear story told in layers of images – like a film where all the frames are shown at once – when the painting is finished, the film is over, but the painting isn’t finished, it continues in the viewer who perceives shifts every time they look at it and all these moments in turn become a film – with no end – a four-dimensional painting.

I continue to paint, every now and then, for a few months. In the dark attic the canvas becomes my only window and also the surface I project on. I don’t paint more faces, instead I paint bodies that bow, pushing, pressing upward or down.

Louise Bourgeois writes that when she creates sculptures she isn’t seeking an image, nor is she seeking an idea, her work is about reliving the past and giving it physical shape. With her sculptures she articulates in the present what she couldn’t or wasn’t able to do in her past. She often talks about working through past fears. Her work is about exorcism rather than beauty. “Fear is a passive state, and the goal is to be active and take control, to be alive here and today. The move is from the passive to the active […] since the fears of the past are connected with the functions of the body, they re-appear through the body. For me, sculpture is the body. My body is my sculpture.”25)Louise, Bourgeois, Deconstruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father, (London: Violette Editions, 1998), 357. Her words resonate with me. I am surprised by the paintings that emerge, even as I see myself in them, they express my body and my feelings.

I’m always scared of what will happen when the images fall away, the images that shield me. But now they’re in my way. When something is taken away, will something else take its place? What?

7.

The blind beggar, who “sees in a way that is all his own”26)Arne Dahl, Blindbock, audiobook, (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 2013)., is one of the main characters in Arne Dahl’s crime novel Blindbock [blind-man’s-bluff]. He’s from Sarajevo, he is one of the Roma that have been purged, now he’s been bought by the director of the home to make money begging, he’s bought by human traffickers. In the novel there’s also a policeman who has a blind son. The blind son helps the father see. The blind person has developed an inner eye, a guiding eye. In a world bursting with the visual, people develop selective seeing, each person’s intuitive eye. We also see each other with that eye. The theologian and former archbishop K. G. Hammar tells me: “In some ways you can be even more aware of someone’s presence when you close your eyes. I can’t stand seeing… you may be far more aware of that person than of others.”27)K. G. Hammar and I spoke about begging people in Lund November 21, 2013.

8.

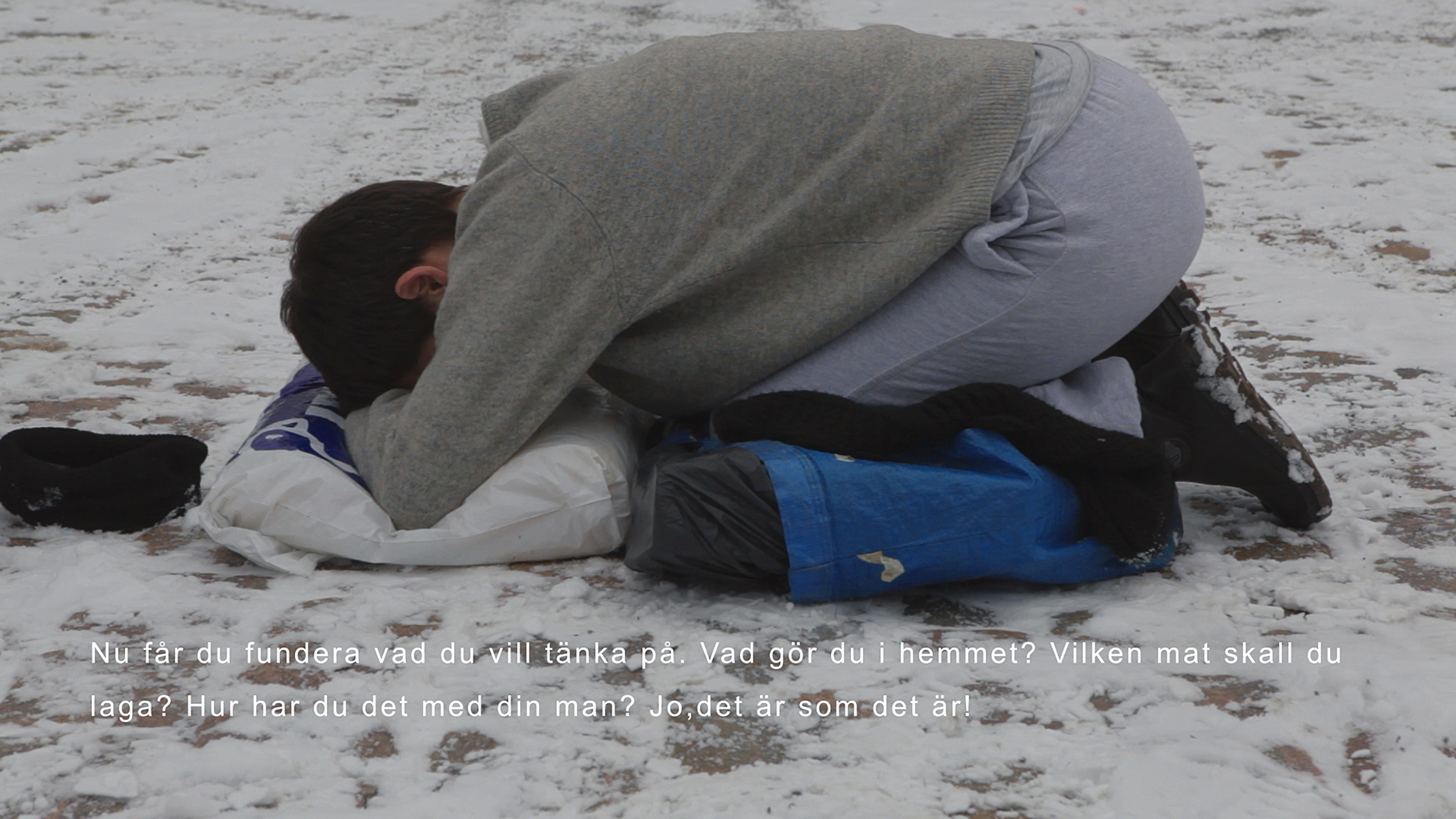

By changing positions, performing gestures that are tied to meanings like representation and power Romanian-Swedish artist Ioana Cojocariu makes visible how the begging person acts according to a social pattern. In the film Kropp – Erfarenhet – Kunskap [Body – Experience – Knowledge] Ioana asks a begging woman to teach her how to lie on her knees.28)Artist Ioana Cojocariu filmed Kropp – Erfarenhet – Kunskap in 2013. The starting point is a pedagogical situation in which the teacher – a woman who is begging on the street in Sweden – instructs and the apprentice – artist Ioana Cojocariu – performs.

——“Lesson # 1, one is instructed to look to the side, but to never look up. Lesson # 2, one is instructed to breathe, lift ones chest and look straight ahead. Lesson # 3, one is instructed to quickly neutralize the opponent, be decisive and never apologize. Can one understand the structure if one follows the instructions? What constitutes bodily knowledge in different forms of work? What is the relationship between economy, pain, and relaxation? Has the private become economic, rather than being political?”

“Kropp – Erfarenhet – Kunskap”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.verkligheten.net/2014/11/kropp-erfarenhet-kunskap/. In a public square she is instructed in how to make sure her legs don’t go numb, to not look passers-by in the eyes, and what to think about to pass the time.

Next in the film a yoga teacher instructs her in the same pose. She demonstrates how the same position can be assigned different meaning and value depending on the social situation. In the first case it is a position performed on the street in order to get money, in the other it is a position performed and paid for out of free will. She draws the viewer’s attention to how our positions are enmeshed in social contexts and valued accordingly. Which social values are pushing the older woman onto her knees on a snow-covered, cold street? It’s violent.

When Ioana demonstrates how the position in one instance is performed as a signal of need and distress, and in the other instance voluntarily as being beneficial to the body – as a yoga pose – she also demonstrates how social bodies express the normative through positions; how they enact the norm.29)One example would be to sit with one’s legs crossed, which some cultures regard as the default position during mealtime, and others think of as a yoga pose.

In the third part of her film she lets a policeman train her in throwing a threatening person to the ground. Perhaps she wants to show the powerlessness inherent in encountering inequality and not being able to fix it. When she’s learned the technique she takes the policeman down – demonstrating empowerment and intent. She has learned how to handle a situation that according to her assessment will require this reaction. To experience inequality can be to experience a crime being perpetrated, meaning that inequality implies a crime – against equality – but there is no police, no guardian of the law, to help fix this crime. The choice then is between powerlessness – social bodies becoming instrumental to a social order – or empowerment.

9.

The question – What pushes the man (in the red jacket in the first photo) onto his knees on a cold street? – is directed at the social context, at the passers-by, as well as at the man himself. George, another one of the begging people gives me an answer. He periodically lives with eight other people in temporary shacks around Sweden. He tells Laura and me how he attempts to handle his existence:

G: We stay here in winter too, what can we do? In Romania we have a house, but we have no work, no social help, the minimum wage is 120 Euro I don’t think you can raise 3 kids, have a five-person family on 120 Euro a month. So yes, it is better here, we collect cans. We survive! If any of us has a problem back home, we collect money together, we all help out and we always send money home to our children, to our families.

L: So all your children are in Romania?

G: Of course! You cannot come here with kids and live in a hut. You struggle by yourself, you are a grownup, but why put children through this? And anyway, here the social workers will pick them up immediately. You cannot raise children under these conditions.

L: Did you try to get help?

G: I went to T-Centralen to ask, handed in my ID-card, all my papers, filled in the papers, and they told me to wait for their call. It’s been five months since then… I also applied at the Solna immigration center, to get an address and work, I went there together with a woman from the Skanstull center, she spoke for me in Swedish, filled in her address on the papers, and… nothing happened. No call. It’s difficult.30)The audio recording is transcribed by interpreter Laura Chifiriuc and is partially reproduced here. The full transcript can be found in the archives.

George testifies to structural violence. How can I hear George? I have no personal experience of what he’s gone through. What binds us as social bodies? Michael Azar, professor of intellectual history, writes about the risks of domesticating the potentially unknown by subsuming it into an existing discursive order. “For instance, in a discourse built on strict dichotomies – sense or sensibility, good or evil, civilized or barbarian, freedom fighter or terrorist etc. – every occurrence will be singled out as being one or the other. No third alternative is given.”31)Michael Azar, Vittnet, (Gothenburg: Glänta, 2008), 46. The third is “something inter-subjective that inserts itself between the subject and the being”, this third is the discourse that is the foundation for whether we can see and understand things the same way. “We don’t have an experience and then understand the meaning of it, they happen at the same time.”32)Ibid., 45. Michael Azar claims: “That is where the experience lacks a name – that it becomes mute, it mutes her and makes her search for words.”33)Ibid., 43. The quote is preceded by: “[…] how can the witness know what an intelligible testimony regarding a certain experience is if she doesn’t already know how ‘one’ should interpret the experience? Rather perhaps we must […] imagine how the names are already more or less given to her and that these are what designate the shaping of the experience.” I can’t stand it! Vinterhed exclaims, groping for a frame of reference – that doesn’t exist – in the common language.34)Azar, 43. “It’s not the subject on one hand and the object on the other: Rather it is the discourse that designates how the relationship between the two will be experienced and lived.” p. 43. How does one testify to that for which there is no words? Sara Ahmed wants to show how actions are reactions, in the sense that what we do is shaped by our contact with one another.35)Ahmed, 6. Ahmed builds her theory on French sociologist and philosopher Émile Durkheim among others. For Durkheim emotions do not emanate from the individual body, rather they are what keeps together, or binds, social bodies.36)Ahmed, 9. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion Sara Ahmed joins the sociologists and anthropologists who claim that emotions – rather than being seen as psychological states – can be seen as social and cultural practices. She describes Durkheim’s reasoning on how individual ideas and tendencies come to us “from without”. Durkheim argues that sociology is about “recognizing constraint”. “Most of our ideas and our tendencies are not developed by ourselves but come to us from without.” (The Rules of Sociological Method, (New York: Free Press, 1966), 4.) He presents a theory on emotion as a social form and presents the example of large gatherings of people generating emotions that don’t tie in to individual “self-expression” (compare to swarm theories). Emotions are also created by something, are oriented around something, involve a stance “on the world” or a way of grasping “the world”.37)Ibid., 7. “Emotions are intentional in the sense that they are ‘about’ something: they involve a direction or orientation towards an object (Parkinson 1995: 8). The ‘aboutness’ of emotions means they involve a stance on the world, or a way of apprehending the world.” Ahmed describes emotions as movements in which bodies orient toward each other, as well as away from each other. Emotions could be described as a power, or a tension between social bodies in community life. An increasing number of testimonies are given in this tension. George’s story is also a story about pain. A testimony of pain that we must take personally. But not even those closest to us can feel our pain. If I break my leg and you hear my pain, but you’ve never experienced a broken leg first hand, you can’t know what it feels like. You can listen to what I say, or perhaps rather to how I express myself. Because emotions are created in the presence of another, they shape us and also shape that which we are in the presence of.38)Ibid., 7. A testimony can be understood by another person the same way the impossible can be understood. Sara Ahmed expresses it thus: “Our task is instead to learn how to hear what is impossible.”39)Ibid., 35.

4.2 About Body on Street

1.

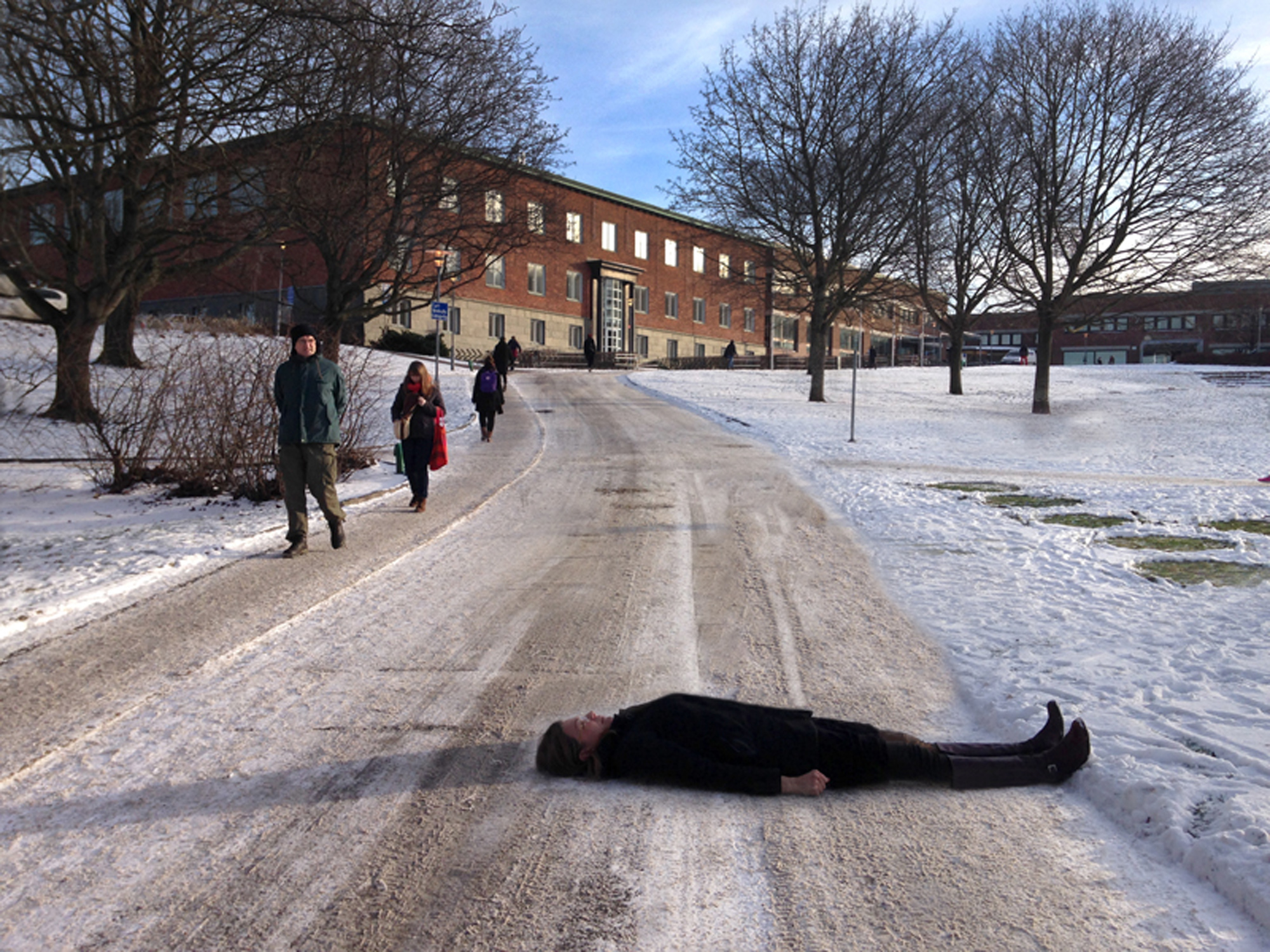

I want to make images of what I as a giver sense physically – that begging challenges giving. In a conversation with Kent Sjöström, theatre arts researcher, he asks me to show him how I move in relation to those who beg. When do the gestures of the body begin to signify that which isn’t said? He then shows me his association – as a physical expression – a position he demonstrates on the street; he lies down in a sort of impossible position – it’s not possible to lie that way for very long, it’s uncomfortable and vulnerable – and I photograph him. This soon evolves into an idea of involving more people: What would others do? I imagine it might become a photo demonstration on social media. This is how Body on Street begins.

The next day I show the photo to a friend and tell him about the conversation. He wants to participate too.

2.

I experience a distance, almost a gulf, between me and those who beg. Overall, it feels like the atmosphere on the street has changed in recent years; something has happened to the social climate that feels substantial, difficult to pin down. Is it solidarity, the ability to be touched? The project aims to make tangible and give shape to a question that is as common as it is impossible to answer: “How does it feel?”

Body on Street began in January 2013, and has been staged in various places and contexts across Sweden. A workshop is held with local people in conjunction to the exhibition, the photos generated in the workshop then become part of the exhibition. Participants are invited via email or notices in newspapers. Participation is free.

In the workshop participants think and associate in images and gestures, on the distance between those who beg and those who give on the streets; political realities that are made visible daily in the Europe of free movement and migration. After the workshop, the photo is published on a project website.40)The photo demonstration began in November 2013. The photos have been mediated through a special website and tied in to previous and future improvisations with a growing number of participants, Body on Street is still ongoing as we write. You can find photos as well as a short text about the idea here: “Body on Street”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.ceciliaparsberg.tumblr.com.

The street is a political arena. The effects of the prevailing policy become visible on the street, but street life also affects policy. My physical actions affect the choreography of the street. Mentally I become my body when I perform the position but in the position I am not just my physical body, I am also the one making my body perform the position, I act and I will be seen a certain way.

Body on Street is performed and presented in three types of spaces: On the streets, in art venues, and social media. Under each photograph is the name of the participant, their title, institution and city, in order to announce the identity of the person performing, and what he or she represents in the community.41)A selection of the photographs from Body on Street – about 25 of them – have been shown as a series in several exhibitions 2014–16. See “Documentation”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.ceciliaparsberg.se/how-do-you-become-a-successful-beggar-in-sweden.

3.

Every Body on Street workshop is unique, but they all have in common that we investigate together at what point the gestures of the body start to signify that which isn’t said, and social body in relation to body politic.

The participants are asked to share a story about an experience, an encounter or a shortcoming, an exchange, or perhaps the opposite, with a begging person. The following is an example of mine:

I’m by the ATM, withdrawing money, when an older woman who is sitting and begging reaches her hand toward me, she wants to take my hand and greet me. My stance is reserved, guarded, but I take it, she raises our hands toward her forehead, I resist, she doesn’t ask for my consent, it feels shameless, boundaryless. I put my hand in my pocket, feel my coins – I’m embarrassed – I drop the coins into her mug. She thanks me.

I ask them to describe how giving feels to them, mentally, what gesture they made and how that can be expressed. Next I ask them to show their conversation partner how they moved in relation to the begging person and to develop a special gesture they made, did they position themselves, take a certain stance? Then I ask each person to hold a feeling, a gesture, and a posture that they’ve found and not try to correct it or free themselves of it. We do a focus exercise that I call social presence, it’s about feeling connected to a social group – while still holding onto that frame of mind or feeling. The purpose of the exercise is to relate to one’s surroundings on the street – in a physical and sensory way. The individual feeling is connected to a social body in the urban landscape that in turn is part of a body politic.42)The exercise is done standing, in a circle. I improvise the exercise, it goes something like this:

Take a few deep breaths and feel your body. If you perform this exercise with your eyes closed, or half closed, you will find it easier to focus. (15 seconds)

—Feel your feeling, your experience of your interaction with a begging person in the experience you just told us about. Can you picture how you moved in relation to one another? Your body remembers the movement. (10 seconds)

—Physical posture is influenced by intention. Feel your intention. (10 seconds)

—Hold the course of events, feelings, and intention for the entire exercise, even if they are vague, try to stay with them. (10 seconds)

—Stay where you are and sketch – by visualizing – a movement and a position for yourself. (20 seconds)

—Feel the presence of your neighbors to your left and to your right. Make light contact with them, touch each other. (15 seconds) Your body is a social body.

—Feel your surroundings, the environment you’re in and feel the social body. We are a part of community life, an ongoing life in society, with our own feeling, our social physicality that can make contact with others. Take a few deep breaths at your own pace and feel all these physical and mental dimensions at once. If you’re feeling stiff you can shake your body out. (10 seconds)

—Open your eyes, tell your neighbor what you felt, what thoughts you have. (10 minutes)

—Change partners and tell someone else. (5 minutes)

—Change partners again and tell each other without words. Hold your hands up in front of you, put your fingers against the other person’s and narrate with movement.

—Choose a place on the street to perform your gesture or position, alone, in couples, or more. Together in our social group we won’t censor anything, but we relate to what’s going and to others on the street.

Liminal areas in community life are charged with emotion. Tensions that boil over, outside, on the side of – is all of this a product of the prevailing system? Now, I’m the one charging and expressing.

Their performative acts are then staged in the public space and documented. The improvisations on the street are quick, the whole thing requires maintaining a certain pace and I try to see to it that we do. I don’t want the participants to spend too much time discussing what they’re doing, if one thinks and talks too much about the gesture one is about to perform, the physical presence is easily lost and one risks self-censoring – I can’t do this, can I… But if a conversation emerges about how to develop the improvisation I’ll slow the pace down, I’ll listen to what is happening within the group and lead it. At one point I noticed that the entire group wanted to act together and then I directed them in performing this position.

4.

Am I performing myself? No. In the act of addressing you – the viewer – I try to transcend my limitations, become dependent on your answer, and when I do, a new image arises, made by us.

Together with the participants, I want to access a kind of creative act that doesn’t describe, but rather affects the environment in which it’s performed. I don’t want the participants to say: “I’m going to lay down on the street as a spectacle for your camera.” Nor should Body on Street be understood as a performance documented with a still camera. It is about finding a movement in a subjective experience, a mental and physical experience of a social situation, to perform it in a new environment, and create a new image. Within the community of the group the body is destabilized, we can work with the social norms that we express physically – the social uncertainty generated by this begging that is relatively new to Sweden. What does a physical expression of lack of results or powerlessness look like? Peggy Phelan writes: “The performance uses the performer’s body to pose a question about the inability to secure the relation between subjectivity and the body per se; performance uses the body to frame the lack of Being promised by and through the body – that which cannot appear without a supplement.”43)Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, (New York: Routledge, 1993), 151. The participants in Body on Street explore the space they inhabit and how their bodies speak with it. When some of the participants want to act together, they examine their positions by balancing their bodies in relation to each other.44)See photos of balancing acts at Medborgarplatsen, Stockholm and others by Korsvägen, Gothenburg. The audience is the people who happen to pass by during the performance.

Through the act of giving in relation to the person begging we reflect and examine the experience of being human in relation to another human. Giving is composed of a variety of intentions, desires, and emotions. Each person has their own specific composition. But each person is also an actor within a social body and performs giving and begging as a transaction within a system. The situation might be termed a spectacle – La Société du Spectacle to use Guy Debord’s title.45)Sven-Erik Liedman prefers the original French title to the Swedish Skådespelssamhället and writes: “Debord links society as spectacle to the evolution of Capitalism and claims that humans in such a society suffer from incurable alienation. In the spectacle Debord sees denial of real life. All of existence is void of content and the only compensation offered are the spectacle’s twisted images of a sustainable community between people, meaningful work, and a healthy sense of self.” Sven-Erik Liedman, Stenarna i själen: Form och materia från antiken till idag, (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 2006), 401. Guy Debord wrote his book in 1967, he was a driving force in the Situationist art movement, which I find topical again, especially in the context of begging-giving and the narratives that emerge about how both the begging and the giving experience the situation. (See chapter 2.) The artist and theoretician Bojana Cvejic describes the close link between performance, image, and representation: “In my imaginary exercise of a theoretical pamphlet in 2015 Debord would be ready to substitute ‘performance’ for ‘image’ and ‘representation’. A ritualized motion based on the psycho-social power of embodiment provides the affective-experiential ground of persuasive expression for the performances of the self.”46)The quote is from her lecture at “TRANSLATE, INTERTWINE, TRANSGRESS!”, a symposium between choreography, philosophy, art, and poetry, with lectures, plays, and parties at the Museum of Modern Art, Stockholm and MDT. June 11–13, 2015 Stockholm. Body on Street is a participatory performance about staging and testing the power of the affective physical movement in a social environment to activate images that exist between us, actualize them, and possibly generate new ones.

Streets are urban forms for urban life. I leave one place and am on my way to another. I cruise past others, stop, become part of a line, wait for a while, continue on in the city. Leaning forward slightly, in stand-by mode, selectively vigilant. The street absorbs me into a social body, a mass of people, the mass moves, not me. The mass takes shape through quiet negotiations, I behave, conduct myself. I am neither seen, nor unseen.

5.

In Walter Benjamin’s interpretation of Brecht, the philosopher seems to imply that the position situated in a flow of behaviors – were it to be isolated – can be identified as an element of a real condition, that it can surprise the viewer precisely because it is a familiar position, but also distance itself from the flow. “The interrupting of action is one of the principal concerns of epic theatre.”47)Walter Benjamin, “What is Epic Theatre?”, Understanding Brecht, transl. Anna Bostock, (New York: Verso 1998), 19.

I see and perceive your compulsion, your lack of freedom, that is why I lie down – in tension – on the street. Straight out and right across. I’m blocking the pedestrian paths with my prostrate body, interrupting the flow of the mass.

The invitation reads: “When I perform a gesture I’m not just my physical body, I’m also a cerebral body. My actions and how I take shape affects patterns in the choreographies of the street.” The staged act becomes a new experience in the urban landscape, breaking with one’s own behavior can bring insight into one’s own position, insight into who one is in a social context, to unframe the framed.

“The supreme task of an epic production is to give expression to the relationship between the action being staged and everything that is involved in the act of staging per se.48)Ibid. 11. This is according to Walter Benjamin. The position expressed by the participants in Body on Street lasts for a few short minutes. It might be reminiscent of Brecht’s way of freezing a movement into another in order to give the viewer the opportunity to consider how we behave to each other – whether one behaves against or with the other, the movement happens in relation to. The room is framed by the photo.

The actor in Body on Street performs their gesture for the group and is also aware that this is about performing a gesture for the camera – they are seen. The camera is the public eye that is an otherwise constant presence on the street, the eye of the public. Brecht’s actors weren’t supposed to “lose [themselves] in the character but rather demonstrate the characters as a function of particular socio-historical relations, a conduit of particular choices”.49)Elin Diamond, Unmaking, Mimesis, (New York: Routledge, 1997). When the performed act in Body on Street, the photographed gesture, is shown together with a number of other people’s gestures, the behavioral break appears more markedly as a common movement – a counter movement – as a demonstration. That is why I call Body on Street a “photo demonstration”.

In 1928 Brecht staged the musical The Threepenny Opera, a politically confrontational, documentary theatre that challenges conventional morals.50)In 1934 he published the Marxist, anti-Capitalist short story. It has been translated into 18 languages and staged more than 10,000 times on stages across Europe. It’s not just an opera about beggars it is also “the beggar’s opera”. This epic theatre continues to be influential, but in order for it to be a contemporary political act it must continuously be rephrased.51)One is example is the Spanish artist Dora García staging The Beggar’s Opera in Munster in 2007, a performance she calls a “Theatrical production in real time and in public space with no clear beginning or end” http://thebeggarsopera.org. If a human is only the sum of their social conditions, if the private is incorporated into a social body and set up in relation to a body politic, they risk becoming instrumental for the purposes of the body politic. Or as Brecht put it, they become material.

6.

Author and playwright Sara Stridsberg describes her experience: “If you don’t give anything you are saying that you accept the prevailing order, the boundary between rich and poor, between the person who seeks help (let us call her the stranger) and yourself. If you choose to give a penny, it always has a larger value than the financial transaction. Regardless. You go on your way through the city with questions like dark claws in your chest […].”52)“Sara Stridsberg”, Sommar i P1, Sveriges Radio, July 21, 2011. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/126264?programid=2071. I’ve had the quote mailed to me by her and am using it with her permission.

When the participants assume a position on the street in front of the rest of the group and my camera it is similar to the way of acting that Brecht terms gestus. The term gestus is relevant in Body on Street as the person physically performing their gesture at the same time expresses an attitude that relates to the social position of those who beg. The actors assume a position on the street that they never would if they weren’t being photographed by me. They give me both their image and their permission – their confidence that I can administer said image. When they give me their image in this manner they destabilize their position. This is about what I previously described in my method and intent as a way of destroying the own image of the image; the imagined image (a prevailing, normative image, a cultural image).53)The process of staging Body on Street follows my methodological intent described in greater detail in the Introduction.

7.

Each person’s motivations, commitment, and actions express a stance, a haltung (disposition). By this Brecht didn’t just mean mental attitude, but also the concrete physical posture. In his thesis, researcher Kent Sjöström discusses how physical and mental attitude affect each other: “In order to complete a task the body must adjust to the prevailing conditions. If the actions describe what a person does, the adaptation to the task also describes how the action is performed.54)Kent Sjöström, Skådespelaren i handling, (Stockholm: Carlsson, 2007), 119, 236. The pleading stance of the beggar and the downward dip of the giver are both socially conditioned actions. They constitute (physical) stances that carry meanings.

8.

The distance between the begging and the giving can be seen and felt on the street, the way givers and beggars relate is often expressed through distancing gestures. It isn’t merely a transaction – I look at you, perhaps approach you, change my position in terms of distance and height, negotiate the physical space with you, our space – between us.

In Body on Street the distancing doesn’t make visible a dialectical relationship, but a new social space – evident since around 2011 due to the begging people who traveled here – in which various emotions are set into motion, where the relationship needs to be re-negotiated. The space can be seen as a liminal one, where images I already have prevent me from seeing and where I must find other ways of relating in order to create new images. The physical act in Body on Street is a way to think through and with the body – to “exercise” the images. Body on Street portrays a sort of verfremdungseffekt that intends to hold a space for the viewer to interpret and think over how the urban landscape feels.55)In the journal Konstperspektiv Bo Borg writes of Body on Street: “One of the image series, Body on Street stands out from the rest. It depicts staged arrangements done together with giving people. People lie on the street in a manner that would be extreme even among the begging. They become social sculptures that highlight the indifference of the passers-by and the fact that the urban landscape has changed. This type of photo has been taken in different places and will also be staged in Skövde.” Bo Borg, “Cecilia Parsberg’s utställning i Skövde Konsthall 7/3–22/5”, Konstperspektiv No. 2 (2015).

Staged Work:

( a photo manifestation )

Body on Street

Chapter 4: Gestures

Notes

| 1. | ☝︎ | “For Aristotle the soul designates the actualization of matter, where matter is understood as fully potential and unactualized”. Judith Butler interprets Aristotle’s De Anima in her book Bodies that Matter, (New York: Routledge, 2011), 32. ——The body is matter. Butler claims that matter doesn’t appear without the schematic: form, shape, expression, and syllogism. The body appears in a certain grammatical form within a discourse of power throughout history. |

| 2. | ☝︎ | Kent Sjöström, Skådespelaren i handling; strategier för tanke och kropp, (Stockholm: Carlsson, 2007), 151. |

| 3. | ☝︎ | Kerstin Vinterhed, “Var finns ambitionen att hjälpa Stockholms tiggare?” Dagens Nyheter, February 14, 2013. Accessed April 27, 2016, dn.se/debatt/stockholmsdebatt/var-finns-ambitionen-att-hjalpa-stockholms-tiggare. |

| 4. | ☝︎ | A matrix is a template that produces structures (patterns, content, meanings beyond the overt message, actions, incidents, and other human contexts). But what kind of template is this? In a world that has experienced the nuclear bomb, the growing gap between the developing world and the industrialized world, environmental destruction, and the dumbing down of the capitalist industry of consciousness there are discussions about how knowledge is produced, so writes Sven-Eric Liedman, who studies the history of ideas and he stresses: “For Marx it is obvious that the large shifts have to do with conditions that lie beyond human consciousness. Consciousness doesn’t create history. In relation to the greater processes, individuals, with their calculations and schemes, are coincidences […] History flows through our lives. The currents are below the surface.” Sven-Eric Liedman, Humanistiska forskningstraditioner i Sverige, (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1978), 48–54. |

| 5. | ☝︎ | “Since my aim is to ask about the relationship between what tragedy shows and what we find intuitively acceptable”. Martha Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness, (Aeschylus and practical conflict), (New York: Cambridge University press, 1986), 26. |

| 6. | ☝︎ | “Art will mediate and adorn, and develop magical structures to conceal the absence of God or his distance. We live now amid the collapse of many such structures, and as religion and metaphysics in the West withdraw from the embraces of art, we are it might seem being forced to become mystics through the lack of any imagery which could satisfy the mind.” Iris Murdoch, The Fire and the Sun, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), 88. |

| 7. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 79. |

| 8. | ☝︎ | Quoted from a seminar with philosopher Tore Nordenstam and Ingela Josefsson, professor of Working Life studies, in the course Kunskapsfilosofi 2, DI, Stockholm, March 22, 2013. |

| 9. | ☝︎ | Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 184. |

| 10. | ☝︎ | “Sara Stridsberg”, Sommar i P1, Sveriges Radio, July 21, 2011. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/126264?programid=2071. Stridsberg emailed me the quote and I am using it here with her permission. |

| 11. | ☝︎ | “Beggars Saturday & Persondesign”. Accessed April 4, 2016, http://reich-szyber.com/en/portfolio/beggars-saturday-persondesign/. |

| 12. | ☝︎ | Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, second edition, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 103. |

| 13. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 103. |

| 14. | ☝︎ | Bäckström, Örestig, Persson, 3. “The moral economy signals that the key to social rights is and should be citizenship and labour market participation.” |

| 15. | ☝︎ | Bäckström, Örestig, Persson, 4. A theory that they credit to American political scientist Kathleen Arnold, Homelessness, Citizenship, and Identity, (Albany: SUNY Press, 2004). |

| 16, 19. | ☝︎ | Ahmed, 105. |

| 17. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 104. |

| 18. | ☝︎ | Bäckström, Örestig, Persson, 4. |

| 20. | ☝︎ | See further reasoning regarding hierarchies of power in chapter 5.1: “Private Business, Public Space”, paragraph 5. |

| 21. | ☝︎ | “Rather, we find ourselves born into communities in which the available ways of acting are largely laid out in advance: in which human activity takes on different […] ‘forms of life’ […] and our obligations are shaped by the requirements of those forms.” Stephen Toulmin, Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity, (New York: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 23. |

| 22. | ☝︎ | “Dharavi Residents Stage Anti-Government Protest”, DNA India, June 12, 2012. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report-dharavi-residents-stage-anti-govt-protest-1701162. |

| 23. | ☝︎ | Stridsberg, www.sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/126264?programid=2071. |

| 24. | ☝︎ | My educational background is in painting, I studied for two years at the Hovedskous art school in Gothenburg, where we did live figure drawing every day. After that I was accepted at Valand Academy where I studied from 1986 to 1991, but I haven’t painted much since then, only during periods when I need to work through experiences, or remember, or when it is the most relevant production technique in a certain project. |

| 25. | ☝︎ | Louise, Bourgeois, Deconstruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father, (London: Violette Editions, 1998), 357. |

| 26. | ☝︎ | Arne Dahl, Blindbock, audiobook, (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 2013). |

| 27. | ☝︎ | K. G. Hammar and I spoke about begging people in Lund November 21, 2013. |

| 28. | ☝︎ | Artist Ioana Cojocariu filmed Kropp – Erfarenhet – Kunskap in 2013. The starting point is a pedagogical situation in which the teacher – a woman who is begging on the street in Sweden – instructs and the apprentice – artist Ioana Cojocariu – performs. ——“Lesson # 1, one is instructed to look to the side, but to never look up. Lesson # 2, one is instructed to breathe, lift ones chest and look straight ahead. Lesson # 3, one is instructed to quickly neutralize the opponent, be decisive and never apologize. Can one understand the structure if one follows the instructions? What constitutes bodily knowledge in different forms of work? What is the relationship between economy, pain, and relaxation? Has the private become economic, rather than being political?” “Kropp – Erfarenhet – Kunskap”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.verkligheten.net/2014/11/kropp-erfarenhet-kunskap/. |

| 29. | ☝︎ | One example would be to sit with one’s legs crossed, which some cultures regard as the default position during mealtime, and others think of as a yoga pose. |

| 30. | ☝︎ | The audio recording is transcribed by interpreter Laura Chifiriuc and is partially reproduced here. The full transcript can be found in the archives. |

| 31. | ☝︎ | Michael Azar, Vittnet, (Gothenburg: Glänta, 2008), 46. |

| 32. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 45. |

| 33. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 43. The quote is preceded by: “[…] how can the witness know what an intelligible testimony regarding a certain experience is if she doesn’t already know how ‘one’ should interpret the experience? Rather perhaps we must […] imagine how the names are already more or less given to her and that these are what designate the shaping of the experience.” |

| 34. | ☝︎ | Azar, 43. “It’s not the subject on one hand and the object on the other: Rather it is the discourse that designates how the relationship between the two will be experienced and lived.” p. 43. |

| 35. | ☝︎ | Ahmed, 6. |

| 36. | ☝︎ | Ahmed, 9. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion Sara Ahmed joins the sociologists and anthropologists who claim that emotions – rather than being seen as psychological states – can be seen as social and cultural practices. She describes Durkheim’s reasoning on how individual ideas and tendencies come to us “from without”. Durkheim argues that sociology is about “recognizing constraint”. “Most of our ideas and our tendencies are not developed by ourselves but come to us from without.” (The Rules of Sociological Method, (New York: Free Press, 1966), 4.) He presents a theory on emotion as a social form and presents the example of large gatherings of people generating emotions that don’t tie in to individual “self-expression” (compare to swarm theories). |

| 37. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 7. “Emotions are intentional in the sense that they are ‘about’ something: they involve a direction or orientation towards an object (Parkinson 1995: 8). The ‘aboutness’ of emotions means they involve a stance on the world, or a way of apprehending the world.” |

| 38. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 7. |

| 39. | ☝︎ | Ibid., 35. |

| 40. | ☝︎ | The photo demonstration began in November 2013. The photos have been mediated through a special website and tied in to previous and future improvisations with a growing number of participants, Body on Street is still ongoing as we write. You can find photos as well as a short text about the idea here: “Body on Street”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.ceciliaparsberg.tumblr.com. |

| 41. | ☝︎ | A selection of the photographs from Body on Street – about 25 of them – have been shown as a series in several exhibitions 2014–16. See “Documentation”. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.ceciliaparsberg.se/how-do-you-become-a-successful-beggar-in-sweden. |

| 42. | ☝︎ | The exercise is done standing, in a circle. I improvise the exercise, it goes something like this: Take a few deep breaths and feel your body. If you perform this exercise with your eyes closed, or half closed, you will find it easier to focus. (15 seconds) —Feel your feeling, your experience of your interaction with a begging person in the experience you just told us about. Can you picture how you moved in relation to one another? Your body remembers the movement. (10 seconds) —Physical posture is influenced by intention. Feel your intention. (10 seconds) —Hold the course of events, feelings, and intention for the entire exercise, even if they are vague, try to stay with them. (10 seconds) —Stay where you are and sketch – by visualizing – a movement and a position for yourself. (20 seconds) —Feel the presence of your neighbors to your left and to your right. Make light contact with them, touch each other. (15 seconds) Your body is a social body. —Feel your surroundings, the environment you’re in and feel the social body. We are a part of community life, an ongoing life in society, with our own feeling, our social physicality that can make contact with others. Take a few deep breaths at your own pace and feel all these physical and mental dimensions at once. If you’re feeling stiff you can shake your body out. (10 seconds) —Open your eyes, tell your neighbor what you felt, what thoughts you have. (10 minutes) —Change partners and tell someone else. (5 minutes) —Change partners again and tell each other without words. Hold your hands up in front of you, put your fingers against the other person’s and narrate with movement. —Choose a place on the street to perform your gesture or position, alone, in couples, or more. Together in our social group we won’t censor anything, but we relate to what’s going and to others on the street. |

| 43. | ☝︎ | Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, (New York: Routledge, 1993), 151. |

| 44. | ☝︎ | See photos of balancing acts at Medborgarplatsen, Stockholm and others by Korsvägen, Gothenburg. |

| 45. | ☝︎ | Sven-Erik Liedman prefers the original French title to the Swedish Skådespelssamhället and writes: “Debord links society as spectacle to the evolution of Capitalism and claims that humans in such a society suffer from incurable alienation. In the spectacle Debord sees denial of real life. All of existence is void of content and the only compensation offered are the spectacle’s twisted images of a sustainable community between people, meaningful work, and a healthy sense of self.” Sven-Erik Liedman, Stenarna i själen: Form och materia från antiken till idag, (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 2006), 401. Guy Debord wrote his book in 1967, he was a driving force in the Situationist art movement, which I find topical again, especially in the context of begging-giving and the narratives that emerge about how both the begging and the giving experience the situation. (See chapter 2.) |

| 46. | ☝︎ | The quote is from her lecture at “TRANSLATE, INTERTWINE, TRANSGRESS!”, a symposium between choreography, philosophy, art, and poetry, with lectures, plays, and parties at the Museum of Modern Art, Stockholm and MDT. June 11–13, 2015 Stockholm. |

| 47. | ☝︎ | Walter Benjamin, “What is Epic Theatre?”, Understanding Brecht, transl. Anna Bostock, (New York: Verso 1998), 19. |

| 48. | ☝︎ | Ibid. 11. |

| 49. | ☝︎ | Elin Diamond, Unmaking, Mimesis, (New York: Routledge, 1997). |

| 50. | ☝︎ | In 1934 he published the Marxist, anti-Capitalist short story. It has been translated into 18 languages and staged more than 10,000 times on stages across Europe. |

| 51. | ☝︎ | One is example is the Spanish artist Dora García staging The Beggar’s Opera in Munster in 2007, a performance she calls a “Theatrical production in real time and in public space with no clear beginning or end” http://thebeggarsopera.org. |

| 52. | ☝︎ | “Sara Stridsberg”, Sommar i P1, Sveriges Radio, July 21, 2011. Accessed April 27, 2016, www.sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/126264?programid=2071. I’ve had the quote mailed to me by her and am using it with her permission. |

| 53. | ☝︎ | The process of staging Body on Street follows my methodological intent described in greater detail in the Introduction. |

| 54. | ☝︎ | Kent Sjöström, Skådespelaren i handling, (Stockholm: Carlsson, 2007), 119, 236. |

| 55. | ☝︎ | In the journal Konstperspektiv Bo Borg writes of Body on Street: “One of the image series, Body on Street stands out from the rest. It depicts staged arrangements done together with giving people. People lie on the street in a manner that would be extreme even among the begging. They become social sculptures that highlight the indifference of the passers-by and the fact that the urban landscape has changed. This type of photo has been taken in different places and will also be staged in Skövde.” Bo Borg, “Cecilia Parsberg’s utställning i Skövde Konsthall 7/3–22/5”, Konstperspektiv No. 2 (2015). |